By Bruce Byfield

One disadvantage of the modern emphasis on the desktop is that people learn about the command line only when they need it. As a result, their knowledge of is often haphazard and full of gaps. For example, for years I've been using the su - command several times a day to log in as root from a virtual terminal on the desktop of my everyday account. I always thought that when you were finished as root, you couldn't return to the everyday account in the same terminal; instead, you had to close the window and open another one. Then I learned, purely by accident, that all I really needed to do was type exit.

Since then, I've discovered that, if pressed, even experts would confess to a similar gap in their knowledge at one time or the other.

In this article, I'll discuss a topic I should have covered months ago: the basics of Bash, the command line used by most GNU/Linux distributions. I'll discuss the basic tools and sources for information, as well as the basics of navigation. Even if you know some of this information, a systematic discussion might fill in gaps in your knowledge. If not, you can always pass on the information to a desktop user to further their education.

The command line is one of the most basic interfaces ever invented. All you have to do is enter the correct string of characters to get the results you need. Right?

Well, not entirely.

This approach works if you approach the command line like a series of magical spells, each of which you must carefully copy before pressing the Enter key; however, if you add any of your own input, even the name to call a saved file, you frequently need to know more.

For one thing, you need to know that, unlike the Windows command line, Bash is case sensitive, treating uppercase letters differently from lowercase letters. For this reason, experienced users tend to avoid capitalizing anything; they don't want to bother dealing with the extra keystrokes.

More importantly, this also means that a file called taxsummary is not the same as one called Taxsummary; if you forget this basic fact, you can waste time trying to locate a file.

Additionally, certain characters are not allowed in the command line in order to avoid confusion. Prohibited characters include a space, which separates out parts of a command; the forward slash, which separates out directory names in a file path (not a backward slash, as in Windows); and characters such as a question mark or asterisk, which are used in regular expressions or wild cards.

These restrictions can cause some conflicts with the desktop, which has more relaxed rules, especially about the use of spaces in file names. However, you can get around these restrictions in several ways. The easiest way is simply to avoid using anything more exotic than a period in the file name and to use an underscore or hyphen instead of a space, the way that old Unix hands do. Almost as easily, you can use single or double quotation marks around file names with spaces or restricted characters in them as a signal that the names should not be read as they normally would.

Or, if you prefer, you can do what is called escaping and place a forward slash in front of a character. The forward slash is a signal that the next character - and only the next character - is not to be read normally. For instance, if you entered Grocery\ list, you would be telling Bash to read the space between the two words as part of a continuous file name. Without the forward slash, Bash would read your entry as two files, Grocery and list.

A typical command has three parts that appear in a set order:

A few commands also have sub-commands that come directly after the command, such as the install or remove sub-commands used by apt-get, the tool used for installing packages in Debian and Ubuntu.

You'll probably notice, too, that many commands are abbreviations that describe their function. For instance, cp copies a file, and ls lists a file. This information comes in handy when you have a purpose in mind, but are unsure what command you need.

One reason that Bash is easier to use than the Windows command line is that it has several built-in tools for making life easier. These tools can be tremendous time-savers - to say nothing of memory aids.

The first of these tools is a command history, which stores the commands that you enter. You can use the Up and Down arrow keys to move through the history and save yourself having to retype long or hard-to-remember commands.

The command history includes all sorts of interesting tricks, most of which are topics for another day. However, one basic tip is to refer back to a previous entry by entering !-[number] and pressing Ctrl+j. For example, if you ran the ls command three entries ago, typing !-3 would automatically display the ls command, but not run it. Alternatively, you could use the structure ![string] to find the last entry in the history that matched the string.

Another time-saver is tab completion. When you have entered part of a path or a command, you can press the Tab key to complete it. If more than one possibility exists, Bash will display them in multi-column form, and you can continue entering letters until only one possibility remains.

For example, if you enter ch, then press the Tab key, you see a list of 22 possible completions. Continue by typing an a, and press Tab again, and the possibilities are reduced to five. Add a t and press Tab, and, this time, the only choice is chattr, whose final letters are added after your typing.

If, like many people, you are using a virtual terminal, you also have basic copy and paste functionality available. You can use the basic commands listed in the Edit menu of your terminal, but, if you prefer, you can highlight some text, then move the cursor to the position where you want to repeat the text and press the left mouse button.

When you are new to GNU/Linux, you soon realize that it has a directory structure completely different from Windows. You will probably quickly learn your way around your home directory, because you can set it up as you please, but, beyond the fact that it is a subdirectory of /home, you may have little idea of the rest of the directory tree. Fortunately, you can use the command man here to read a summary of the main directories. From that, you can learn, for example, whether a command is more likely to be in /bin or in /sbin, where only the root user can run it.

Another point that you soon learn is that your home directory is full of configuration files that start with a period and are not ordinarily listed when you run the ls command. These are not listed because most of the time you do not want them - and, perhaps, because if they are out of sight, you are less likely to tamper with them. The fact they are not listed does not mean that you cannot use the cd command to move into them, but, if you need to see their names, then ls -A will reveal them.

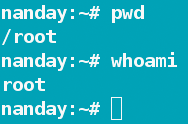

If you get lost in the directory structure while in the command line, you can use pwd, which is short for "present working directory" to get your bearings. If you have been switching accounts and want to be sure, for example, that you are not running a dangerous command as root, then the whoami command will tell you the name of the account that you are currently using. If, however, you find yourself continually forgetting the current account name, you might want to research how to add it to your command prompt (Figure 2).

As you enter commands, Bash also has several ways to save time and reduce typing. Unless a full path is given, any files or sub-directories that you type are assumed to be in the present directory. However, if you want to be absolutely sure (which is never a bad idea), you can use ./ to indicate the present directory. For instance, if you are in a user account named bruce, then typing /home/bruce/download is the same as typing ./download. If your sub-directories are several levels deep, then this piece of shorthand can significantly reduce your typing.

There are also several different shortcuts that you can use with the cd (change directory) command:

These last two shortcuts explain why you often see references to the home directory reduced to a tilde. For example, if you see a reference to ~/.bashrc, it is indicating the .bashrc configuration file in your home directory.

As you work at the command line, you will undoubtedly come across unfamiliar commands, many with more options than you can easily remember. If all you want is a quick explanation of a command, you can use apropos or what is. The only trouble is that, while these commands can serve as reminders for veteran users, their output is often cryptic to the less experienced. For example, if you enter apropos chmod, the definition you receive is "change file mode bits," which is geeky enough to scare off most beginners (Figure 3).

You can get more detailed information by typing man followed by the name of the command. However, the quality of so-called man pages varies wildly. Although some pages, especially more recent ones, read easily enough, others are written for an expert audience. In fact, some may have remained almost unchanged for a decade or more.

In theory, info pages - the explanatory notes you receive when you enter info followed by a command name - are more user-friendly than man pages. And, in practice, they often are. However, they are sometimes little better than the worst man pages and can vary almost as much. Moreover, the original impetus to help info pages evolve into a replacement for man pages seems to have weakened in recent years, and the quality varies.

Often, the most useful help you can find is to use the -h or --help option for a command, which produces a short summary of options. What is missing, however, is any sort of built-in help that allows you to enter a description of the action you would like to perform and receive a list of possible commands. Unfortunately, the options here are the only ones available to you without searching on the web.

Naturally, there is more to Bash than detailed here. Bash is such a large subject that it takes years to learn its intricacies. In fact, it is so large that few people can claim to know it completely.

However, the points I mention here should serve as a general orientation. If nothing else, they should be enough to show that Bash is a flexible program with countless ways to save you effort - if only you take the time to learn. If you familiarize yourself with these basics, you should know enough to really take advantage of the usefulness of Bash.