Using UUDeview can relieve you of the problems associated with sending and receiving binary e-mail.

When did you last send or receive an e-mail? Right. The WWW is fun to surf, but the true killer application on the Internet is e-mail. Another similarly popular service is the Usenet, where you can directly address a desired target audience. There is no doubt that these two services are the most personal.

Suppose you want to smile at your pals? Or that you're red with anger? We all know the “emot-icons” to use here. However, you will see no emot-icons on the Web; instead you will see icon smilies or maybe even a photograph of a smile. These same symbols would be more effective in e-mail than emot-icons, and a threatening roll of thunder could really frighten your reader. “Now, that's impossible,” you'll say—and you're almost right. But why?

E-mail service was conceived in the infant days of the Internet, and the Usenet actually started as an off-line network, where messages were distributed via slow modem lines. At that time, transferring large amounts of data like graphics or audio messages was inconceivable, and both systems were designed to handle only plain text messages.

When the available bandwidth increased, people realized that exchange of binary data instead of just ASCII messages should be possible. Now the design limitations became obvious. But instead of going back to the drawing board with their systems, an algorithm was introduced to encode binary data into plain-text messages, thus bypassing the problem—uuencoding was born. Using this algorithm, three arbitrary bytes were encoded in four printable characters which could then be safely transported with the old software. On the other end, the recipient could decode the data back into its original form.

Unfortunately, the original uuencoding algorithm wasn't perfect, and several other encodings were launched. First xxencoding, then a slightly revised uuencoding, the BinHex encoding, which also took care of both the special characteristics of Macintosh files and the slightly better-compressing ship and btoa encodings. The chaos was complete—you needed different tools for each of them.

Finally, MIME (Multipurpose Internet Mail Extensions) came into being. This standard enabled the effortless transportation of binary data by introducing Base64, another encoding algorithm. It also addressed other issues such as content presentation and the required localized character set for international messages. With MIME encapsulation, a combination of text, audio and video can be sent in a single message along with instructions (for example, whether the audio is to be played along with the video or afterwards). Using these capabilities, you can add graphic icons to your text and underline the message with deafening thunder. You can also send your message as HTML with links to your home page, or as a fully formatted PostScript document. MIME can significantly update the look of e-mail and the Usenet, making the Internet a happier place.

But life just isn't that simple. Although the MIME standard was first published in 1992, it hasn't been widely accepted despite its many advantages. Some small improvements have made the jump into real life (such as the Content-Type header), but the full capabilities have yet to be exploited. Still, most binary data posted on the Usenet is encoded using uuencoding, and some Windows-based email software uses BinHex encoding by default. If you are still using the mail and Usenet software that has served you so well over the years, you are probably stuck with decoding the Base64 data used in MIME messages as well.

Until all users have switched to MIME-compliant software, you must save the messages from your mail or Usenet reader into a file and dissect that file with various tools in order to extract the images and audio clips. And even then it is amazing how much can go wrong.

After being disappointed by many similar tools, I developed my own “Smart Decoder” to address the various problems I encounter when receiving an encoded file.

The resultant decoder is a tool called UUDeview. Despite its early development stage—its version number is 0.5—it does its job well. It can read plain encoded data and whole message folders, which are automatically sorted, grouped and threaded in case any data is spread over more than one message (the dreaded multi-part messages). The user can instruct the program to decode each file or not. UUDeview also handles uuencoding, MIME's Base64 and BinHex.

The UUDeview package comes complete with UUEnview. UUEnview has a big advantage over the standard uuencode in that it can directly mail or post files from the command line, either uuencoded or as proper MIME messages.

Both tools can be installed to replace the standard programs uuencode and uudecode, mimicking their command-line syntax, while adding full power to both the encoding and, in particular, the decoding process.

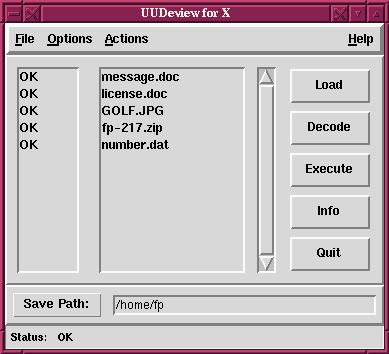

For users who prefer the mouse over the keyboard, a Tcl/Tk-based interface is also included. Alas, I can usually finish decoding from the command line more quickly than the GUI can start up.

Figure 1. Screen Shot of UUDeview Interface

Since development was done on a Linux box and other Unices, the code is highly portable. In the latest release, the programs are built around an encoding and decoding library. Using this library, a programmer can not only easily write different user interfaces (an example of a trivial decoder is 37 source lines in C), but also can use the decoding power of the library in other applications with a small amount of effort. From the web page (see below), you can currently download patches to the elm mail software and the nn news reader. After integrating the patches, you can tag the mail and articles as usual, then decode any binaries with the touch of a button.

Once the whole world has switched to MIME, UUDeview can finally “Rest In Peace”, but until then, it can save you some frustration when trying to read binary mail and news articles. UUDeview is distributed free under the terms of the GNU General Public License and can be downloaded from http://www.uni-frankfurt.de/~fp/uudeview/.