This article covers the use of the Java Development Kit on a Linux platform. It includes a general introduction to Java, installing the JDK 1.1.6, compiling Java support into the Linux kernel, writing a simple Java program and studying an example.

Although several ongoing projects have the goal of porting Sun's Java Development Kit (JDK) to Linux, for the purpose of this article I will look at the largest and most stable effort. It is hosted by the Blackdown Organization, with much of the effort coming from Randall Chapman (for JDK 1.0) and Steve Byrne (for JDK 1.1). At the time of this writing (August 1998), JDK 1.1.6 version 3 was in beta testing. This version will be publicly released by the time this magazine is printed. See the Blackdown's web page at http://www.blackdown.org/java-linux.html for up-to-date information on the JDK port for Linux.

Note that I use the Caldera Open Linux 1.2 Standard distribution of Linux, so I will discuss the JDK installation with respect to that distribution. The JDK 1.1.6 port to Linux is quite stable on Caldera Open Linux 1.1 and 1.2 out-of-the-box installations. It will also work with many other distributions of Linux.

The Blackdown Java Linux porting effort still needs volunteers. Please feel free to contact them. In fact, I received an e-mail message from Steve Byrne stating that the source code is not hard to understand and many areas besides debugging need volunteers. He also said many areas of specialization exist in the source code, so if you are good at one thing but not another, please don't let that stop you from volunteering.

I will review the high points of three different JDK files, drawing on personal experience. The main source of information is the Java Linux FAQ at the Blackdown site. The first file is http://www.blackdown.org/java-linux/docs/faq/FAQ-java-linux.html. The two other files are the README that comes with Sun's JDK and the README.linux that comes with the Linux port of the JDK. These two files are found in the jdk1.1.6 directory after installing the JDK. There is also a link to README.linux from the Java-Linux FAQ.

Two types of Java programs exist: applications and applets. Applets are simply small Java programs that run within the context of a web browser. Applications are stand-alone programs.

Both applications and applets start as Java source code files. When a Java program is compiled, the source code is turned into Java byte code. In general, a byte-code file is generated for each “class” declared in your source-code file. These byte-code files have the extension “.class”.

The byte code is then interpreted by the Java Virtual Machine (JVM). Unless you have a machine that implements Java byte code in hardware, the JVM is a program run by the operating system you are using. This is the case under Linux.

As I stated before, the difference between applications and applets is revealed by the way each is started. An application is started from the command line. It is a stand-alone program. In contrast, an applet is started by a web browser.

When an application is written, a method called main is defined. Execution of the application starts in main. To start an application at the command line, type java SomeApplication. Please note that you do not type in the .class extension.

An applet has a method called init. In addition to the applet byte code, an HTML file exists which contains an <APPLET ...> </APPLET> tag pair defining the location of the byte code and other useful information. When the applet is started from within a web browser, init is called to start the applet. An applet can be started from the command line with a program called appletviewer. This program, distributed with the JDK, takes the name of an HTML file, finds all applet tags and runs those applets.

Both main and init can be implemented in a single Java program. The resulting program can therefore be started by either java SomeApplication or with a web browser.

As I mentioned above, the Blackdown Organization is the repository for the largest Java Linux effort. This site contains distribution locations, e-mail lists and known problems with the current JDK for Linux. Currently, the latest release of the Java Development Kit for Linux is JDK 1.1.6 version 3.

JDK comes in two flavors: one for libc and one for glibc. For an explanation of the differences, see the Java-Linux FAQ. According to the README.linux file that comes with the JDK, a good way to determine which version you need is by looking at the libraries installed on your system. This can be done with the following command:

ls -l /lib/libc.so.*

If the files are libc5, you should download the libc version. If they are libc6, then you should download the glibc version.

To download the JDK distribution, point your web browser to http://www.blackdown.org/java-linux/mirrors.cgi. This page lists sites that distribute the JDK. You can obtain the Linux JDK port only from a mirror of Blackdown.

Take a look at the mirrors, and choose a download site near you. Since Caldera uses libc5, I followed the links to JDK-1.1.6/i386/libc/v3/. Download the file jdk1.1.6-v3-libc.tar.gz. You can also download other files from this directory.

Choose a directory to unpack the distribution using the tar command. I chose /usr/local/. If you choose a different directory, use that directory in place of /usr/local/ wherever it appears in the rest of this article. Once you've picked a directory, go to it using cd, then type:

tar xzf jdk.1.1.6-v3-libc.tar.gz

The installation of JDK is complete. You should now visit JavaSoft to download documentation. Please see http://www.javasoft.com/docs/index.html for download and installation instructions.

To complete the setup, you should modify your PATH environment variable to include the location of JDK wrappers. Using your favorite editor, edit the appropriate startup file (for me, this was .profile) and add /usr/local/jdk1.1.6/bin to your PATH. Adding this to the beginning of your current PATH setting ensures that this JDK is invoked.

You also need to add two new environment variables: JAVA_HOME and CLASSPATH.

JAVA_HOME tells JDK where its base directory is located. Although it isn't mandatory to set this variable since the JDK does a good job of determining this location, it is used by other Java programs such as the Swing Set.

CLASSPATH can be confusing and frustrating, but it is possible to use it well and correctly from the beginning. Just remember this simple analogy: CLASSPATH is for Java what PATH is for a shell on your machine. Looking closer at the analogy, your shell executes only those programs or scripts residing in the directory pointed to by PATH, unless the full path of the program is specified. CLASSPATH works the same way for Java. Only those applications and applets in the directories specified by the CLASSPATH environment variable can be run without specifying the complete location.

I usually set CLASSPATH to a simple dot. This lets me run any application that is in my current directory. I also create scripts that set my CLASSPATH on an “as needed” basis, depending on what I am doing during that particular session.

If you use bash as your shell, these three environment variables can be set as follows:

PATH=/usr/local/jdk1.1.6/bin:$PATH CLASSPATH=. JAVA_HOME=/usr/local/jdk1.1.3" export PATH CLASSPATH JAVA_HOME

Note that the RPMs which come with Red Hat 4.1 and 4.2 do not work out of the box. I recommend erasing the RPMs and using the JDK distribution from Blackdown. Erase the RPMs with the commands rpm -e jdk and rpm -e kaffe.

You're now ready to test the JDK. Either log in or execute the startup file to set your new environment variables, and make sure the new environment variables are indeed taking effect. Executing rlogin localhost will do the trick.

Now, type java. A message giving usage parameters should appear. Typing javac should also work, displaying different usage parameters.

Next, use your favorite editor and type in your first Java program; name this file HelloLinux.java.

public class HelloLinux {

public static void main (String args[]) {

System.out.println("Hello Linux!");

}

}

To compile this program, type javac HelloLinux.java. The compilation process creates a single file called HelloLinux.class. To run your Java application, enter java HelloLinux. This outputs the single line “Hello Linux!”

The Linux kernel is capable of detecting Java byte code and automatically starting Java to run it. This eliminates the need to type java first. When the kernel is configured with Java support, you need do only two things. First, change permissions of your .class file to make it executable using the chmod command. Then, run it like any normal script or executable program.

For example, after compiling the Java program HelloLinux, perform the following commands:

chmod 755 HelloLinux.class ./HelloLinux.class

Note that you now have to specify the full name of the application. This includes the .class extension.

To set up Java support, you need the source code to the Linux kernel. The default installation of Caldera OpenLinux installs the kernel source code for you. Use this or download the latest and greatest kernel source and install it.

If you haven't compiled a kernel for your Linux box before, I recommend doing it once or twice to get a feel for it. This will also ensure that problems unrelated to Java don't arise when you are trying to add native Java support to the kernel.

Three steps are required to set up the kernel to automatically run Java byte code. You can find more information about using this feature of the kernel in Documentation/java.txt in your kernel source tree.

In the “Code Maturity Option” menu, select “Prompt for development and/or incomplete code/drivers”. The support of Java is still somewhat new and may have problems which not everyone is prepared to encounter.

In the “General Setup” menu, select “Kernel Support for Java Binaries”. Mark it as either a module or a part of the kernel.

Before compiling the kernel, edit the fs/binfmt_java.c file and place the path to your java interpreter in the #defines located at the start of that file. (For me, this path is /usr/local/jdk1.1.6/bin/java/.) Also, edit the path pointing to the applet viewer. An alternate method is to leave the paths alone in fs/binfmt_java.c and make symbolic links to the appropriate locations.

If you compiled Java support as a part of the kernel—i.e., it was not a module—then there is still another way to tell the kernel where your java wrapper lives. Log in as root and issue the command:

echo "/path/to/java/interpreter" >\ /proc/sys/kernel/java-interpreterNote that this command needs to be executed each time you boot the kernel, so you should place it in the rc.local file or an equivalent location.

JDK includes many examples in addition to the applets and applications. Change the current path to /usr/local/jdk1.1.3/demo/ and you will see the numerous directories containing examples in this directory. Some of the examples include Tic-Tac-Toe, a graphics test and a molecule viewer.

To run Tic-Tac-Toe, use your web browser to open the file /usr/local/jdk1.1.6/demo/TicTacToe/example1.html.

The graphics test is located in jdk1.1.6/demo/GraphicsTest/. It is noteworthy for having been written to be executed as both an application and an applet.

The molecule viewer is an applet located in jdk1.1.6/demo/MoleculeViewer/. I mention it just because it is cool—it shows off the power of Java.

The company I work for, Visualize, Inc. (http://www.visualizetech.com/), specializes in high-end data-graphing software also known as data visualization. Our products all derive from our core library called VantagePoint. VantagePoint is 100% Pure Java certified. Writing our products in Java allows us to develop the software once, then run it on any platform for which Java has been ported. In practice, our customers have encountered few problems with the products as a cross-platform software package. In fact, the earliest version of VantagePoint was developed completely on Linux. Linux still plays an important role in our company.

VantagePoint products, as a graphing solution, view the world as data sets. The possible operations on a data set are graphing, loading and analyzing. After an analysis has been performed on a data set, it is possible to do any of these operations again. A useful sequence of operations is opening and loading a data set, graphing the data to get a visual representation, analyzing the data and then graphing the result of the analysis.

One VantagePoint product, DP Server, is a manager for any data sets you may have. It also allows connections from applets running in a web browser on either an Intranet or the Internet.

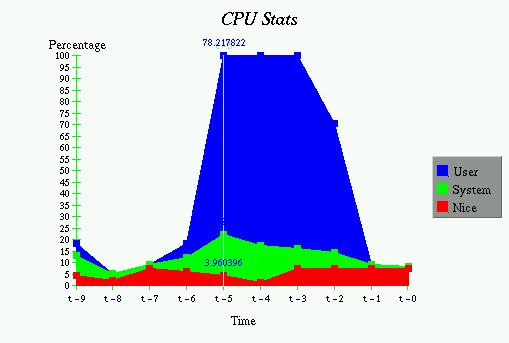

Figure 1: Real-Time Linux CPU Usage Statistics

Now, go to the page at http://www.visualizetech.com/lj/. Follow the link to “Linux Statistics”. This page, which looks like Figure 1, starts a Java applet that connects to a DataPoint Server to show a two-dimensional line chart. It is updated regularly with each update showing the current CPU usage on the Linux web server. During this particular snapshot, the Linux box had just finished compiling the HelloLinux.java program.

Java is a boon to the software development industry. Java and Linux offer the best combination the computer industry has to offer: a free, dependable operating system and a platform-independent software language.