If you work with multiple platforms, LTOOLS may offer a way to make your life a whole lot easier.

The LTOOLS under Windows provide a functionality similar to the MTOOLS under Linux: They let you access your files on the “hostile” file system.

At the heart of the LTOOLS is a set of command-line programs, which can be called from DOS or from a DOS-Window in Windows 9x or Windows NT. They provide the same functionality as the well-known LINUX commands ls, cp, rm, chmod, chown and ln. Thus, under DOS/Windows you can do the following:

list Linux files and directories (command: ldir)

copy files from Linux to Windows and vice versa (commands: lread, lwrite)

delete or rename Linux files (commands: ldel, lren)

create symbolic links (command: lln)

create new Linux directories (command: lmkdir)

modify a Linux file's access rights and owner (command: lchange)

change the Linux default directory (command: lcd)

set the Linux default drive (command: ldrive) and

show your hard disk partition setup (command: ldir -part)

As with many UNIX tools, these functions are included in a single executable, which is called with a bundle of command-line parameters. To make life easier, a set of batch files (shell scripts) are provided so that you don't need to remember and type in all these parameters.

Additionally, there is a UNIX/Linux version of the LTOOLS, to be used under Solaris or even Linux, when you want to access a file on another hard disk partition without mounting this partition.

Some may feel that command-line programs are old-fashioned and ask, “Where is the LTOOLS graphical user interface?” Well, no problem: Use LTOOLgui. LTOOLgui, written in Java using JDK 2's Swing library, provides a Windows Explorer-like user interface (Figure 1). In two sub-windows, LTOOLgui shows your DOS/Windows and your Linux directory trees. Navigating can be done with the usual point-and-click actions. Copying files from Windows to Linux or vice versa can be done by copy-and-paste or by drag-and- drop. Clicking the right mouse button will open a dialog to view and modify file attributes like access rights, GID or UID. Double-clicking on a file will start it, if it is a Windows executable, or open it with its associated application. This even works with Linux files if they have a registered Windows application.

By the way, you can also use LTOOLgui as a file manager under Linux. As the LTOOLS command-line programs also come in a Linux version, you may access files on disks without mounting them.

I chose Java for LTOOLgui, because Java is especially suited for low-level hard disk access...only joking! No, of course, this is not possible in Java at all. If you want to access hardware directly, you have to use C++ code and JNI (Java to Native Interface). However, as the JNI only works for 32bit code, under Windows 9x this would mean using 32-bit to 16-bit thunking (see below). As I did not like the idea of combining Sun's Java with Microsoft's MASM code, I took another approach. I simply used LTOOLS' command line program, which gets called from Java via the well-known stdin/stdout- interface. So for the Java side, hardware access means simple stream-based file I/O.

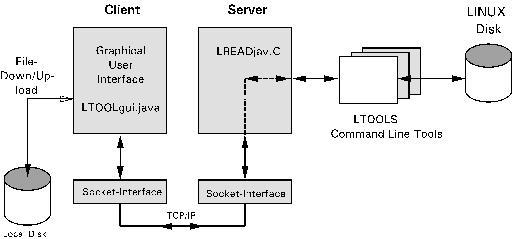

No doubt, any state-of-the-art program must be Internet aware. Well, if you run LREADjav on a remote computer and connect to it via LTOOLgui's connect button, you may access Linux files on this remote server as if they were local. LREADjav is a simple server dæmon, which translates requests, issued by LTOOLgui over TCP/IP, into LTOOLS command line program calls. The output of the command line programs is sent back via TCP/IP to LTOOLgui (see Figure 2). Of course, you can not only view directory listings, but also do everything remotely, that you can do locally, including file upload and download. The remote machine may run UNIX/Linux or Windows. At this point, this is more like a toy than a serious application, because LREADjav can pose security problems. In the default configuration, it can only be used from “localhost”, but it can be configured to allow connections from three different remote clients. As they are identified via their IP address only, there is no password protection or the like. However, if a user has a serious need for that, he can easily implement a login/password scheme...it's all open source!

Figure 2. LTOOLgui for Remote Access

Maybe you don't have Java 2 installed. Well, no problem, as long as you have a web browser. Start LREADsrv and your web browser and as URL type http:localhost (see Figure 3). Now, your Linux directory listing should show up graphically in your web browser. LREADsrv is a small local web server, that, via a simple CGI-like interface, makes the LTOOLS accessible via HTTP-requests and converts their output dynamically into HTML pages (see Figure 4). Of course, not only does this provide local access, but it also allows remote access via the Internet. However, for remote users, LREADsrv does have the same low level of security as LREADjav.

Because LREADsrv is based on HTML forms, which do not support drag-and-drop or direct copy-and-paste, working with your web browser is a little less convenient than working with the Java based GUI. Nevertheless it provides the same features.

As DOS/Windows itself does not support interfaces to foreign file systems, the LTOOLS must access the “raw” data bytes directly on the disk. To understand the internals of the LTOOLS, you need to have a basic understanding of the following areas:

How hard disks are organized in partitions and sectors and how they can be accessed, i.e., how “raw” bytes can be read or written from disk.

Where this information can be found.

How Linux's Extended two-file system is organized.

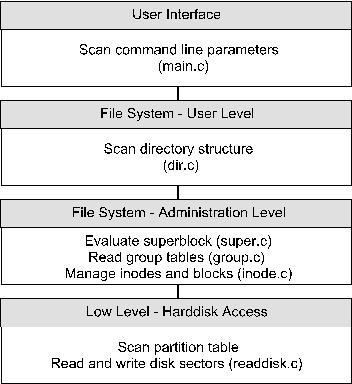

This automatically leads to the layered architecture of the LTOOLS kernel (see Figure 5), which consists of several C files:

Figure 5. LTOOLS Layered Architecture

The lowest layer, layer 1 (in file Readdisk.c), physically accesses the hard disk. This layer deals with (nearly all) differences between DOS, Windows 9x, Windows NT and Linux/UNIX concerning direct hard disk access and tries to hide them from the higher layers (more about that soon).

Layer 2 deals with the UNIX typical inode, block and group structures, into which the ext2 file system is organized.

Layer 3 manages the directory structure of the file system.

The highest layer 4 (in Main.c) provides the user interface and scans the command-line parameters.

Life was easy in the good old days of DOS. There was only one way for low-level read or write access to your hard disk: BIOS interrupt 13h /3/. BIOS data structures limited hard disks to 1,024 cylinders, 63 heads and 255 sectors of 512 bytes, or 8GB. Most C compilers provided a function named biosdisk(). This function could be directly used without needing to code in assembly language. Some years ago, in order to accommodate bigger hard disks, “extended” int 13h functions were introduced. To overcome the BIOS limitations, these functions used a linear addressing scheme, logical block addresses (LBA), rather than the old cylinder-head-sector (CHS) addressing.

This still works in Windows 9x's DOS window (see sidebar) as long as the program is compiled with a 16-bit compiler, at least for read access. (The LTOOLS use Borland C, the Windows NT version compiles with Microsoft Visual C, the UNIX/Linux version uses GNU C.) If you want low-level write access, you need “volume locks” /3/. This mechanism informs the operating system that your program is performing direct disk writes bypassing the operating system drivers, so that Windows can prevent other programs from accessing the disk until you're done. Again, this can be done without assembly programming by using the C compiler's ioctl() function.

In a 16bit Windows program, BIOS functions can only be called via DPMI. As most C Compilers do not provide wrapper functions, this would require an in-line assembler. However, Win16 does not allow command line programs at all, so don't worry.

In Windows NT's DOS box, using BIOS int 13h will lead to a GPF (General Protection Fault). Due to safety reasons, Windows NT does not allow direct hard disk access bypassing the operating system. However, Microsoft provides a solution that is nearly as simple as what you would write under UNIX/Linux:

int disk_fd = open("/dev/hda1", O_RDWR);

This would open your hard disk's partition /dev/hda1; to read, you would call read(), to write you would call write(). Simple and straightforward, isn't it? Under Windows NT, if you use the WIN32 API /5/, function CreateFile() does not only allow the creation and opening of files, but also disk partitions:

HANDLE hPhysicalDrive =<\n>

CreateFile("\\\\.\\PhysicalDrive0",

GENERIC_READ | GENERIC_WRITE,

FILE_SHARE_READ | FILE_SHARE_WRITE,

0, OPEN_EXISTING, 0, 0 );

Reading and writing disk sectors can now be done via

ReadFile() and WriteFile().

You might think that you could use the same Win32 function under Windows 9x. But, if you read on in the documentation for CreateFile(), you will find:

Windows 95: This technique does not work for opening<\n> a logical drive. In Windows 95, specifying a string in this form causes CreateFile to return an error.

Under Windows 9x, Microsoft's Win32 documentation recommends to call BIOS Int 13h via VWIN32, one of the system's VxDs (kernel drivers). However, if you try to do so, you won't succeed. Problem report Q137176 in Microsoft's Knowledge Base states that, despite what the official Win32 documentation says, this only works for floppy disks, not hard disks. As the problem report says, for hard disks, the only option is to call BIOS Int 16h in 16bit code. To call 16bit code from a 32bit program, you need Microsoft's “32bit to 16bit thunking”. This is not only another API (with other undocumented features or documented bugs?), thunking also requires Microsoft's thunking compiler, which from a definition script generates assembler code. From that, a 16bit and a 32bit object file must be generated using Microsoft's assembler MASM. These will be linked with some dozen lines of C-code, which you have to write, resulting in a 16bit and a 32bit DLL (dynamic link library). By the way, you need not only 32bit Visual C++ for this, but you must also have an old 16bit version of Microsoft's C compiler. Using a bundle of proprietary, not widely used tools is not a good solution for an open-source software tool like the LTOOLS!

In summary, there must be separate versions for DOS/Windows 9x, Windows NT and Linux/UNIX. To hide this from the user as far as possible, LTOOLS tries to find out under which operating system it is running and automatically calls the appropriate executable.

Using the LTOOLS may, to a certain extent, pose security problems. Any user may access and modify files on the Linux file system; change file access rights or file owners; exchange password files, and so on. However, this is possible with a simple disk editor, too. Nevertheless, unlimited access is only possible if running DOS or Windows 9x. Under Windows NT, the LTOOLS user needs to have administration rights to access the hard disk directly. In most standard installations of UNIX/Linux, only the system administrator has access rights for the raw disk devices /dev/hda, /dev/hda1, etc.

The LTOOLS are not the only solution for accessing Linux files from DOS/Windows. Probably, Claus Tondering's Ext2tool /6/, a set of command line tools developed in 1996, was the first solution for this problem. However, Ext2tool is restricted to read-only access and does not run under Windows NT. Based on the Ext2tool, in 1997, Peter Joot wrote a windows NT version, still limited to read only /7/. Both programs were written in C and source codes are available.

John Newbigin provides us with Explore2fs /8/, which comes with a very nice GUI and runs under Windows 9x and Windows NT. With read and write access, it provides the same features as LTOOLgui. By the way, John has done great work; he even managed to implement Microsoft's 32bit to 16bit thunking (see above) under Borland's Delphi! All Delphi programs Explore2fs integrate 'seamlessly' into Windows, but porting to non-Windows operating systems may be difficult.

The first version of the LTOOLS, with the original name “lread”, was created by Jason Hunter and David Lutz at Willamette University in Salem, Oregon. This first version ran under DOS, could show Linux directory listings and copy files from Linux to DOS, and was limited to small IDE hard disks and Linux on primary partitions.

I took over maintenance and further development in 1996. Since then, the LTOOLS have learned to deal with bigger hard disks, access SCSI drives, and run under Windows 9x and Windows NT. They have additional write access and were ported back to UNIX run under Solaris and Linux itself. They now have a web browser-based and a Java-based graphical user interface, etc. Many Linux users, most of them named in the source code, helped in testing and debugging. Thank you.

In the meantime, LTOOLS reached version V4.7 /1/ at the time this article was written. Besides additional features, a lot of bugs have been fixed—and most likely new ones have been introduced. A common problem has persisted over the years: Nobody foresaw the rapid advances in hard disk technology, where disk sizes have exploded and consistently hit operating system limits. Do you remember DOS's problems with 512MB disks, Windows 3.x problems with 2GB partitions, BIOS's limit at 8GB and the various problems that Windows NT had at 2GB, 4GB and 8GB? It was only a short time ago. And, by the way, even Linux has its problems. In kernels previous to 2.3, no file could exceed 2GB, as Linux, like most 32bit UNIX systems, uses a signed 32bit offset pointer in read() or write(). (This is resolved in kernel 2.4 by changing offsets to 64bit values, but maintaining upward compatibility may drive Linux into the same problems that we discussed for Windows above.) Software standardization for disk access has always occurred much slower than the disk developers pace, so they invented proprietary solutions to overcome the operating system limits. As always, the developers of LTOOLS—and many other programmers—had to deal with it. So don't be angry if the LTOOLS don't work for you on your brand new 64GB drive. It's open source, so simply try to help debug and further develop them.

Don't forget, if you use the LTOOLS, you do so at your own risk! Read-only access to Linux is not critical. However, if you use write access to delete files or modify file attributes on your Linux disk, the LTOOLS—and you as the user—can create a real mess, so always keep a backup.