Techniques and scripts for automating scanning of log files produced by ipchains.

Firewalls are computers dedicated to filtering particular kinds of network traffic between two networks. They are usually employed to protect a LAN from the rest of the Internet. Securing every box on the LAN is much more costly and time consuming than deploying, administering and monitoring a single firewall. A firewall is particularly essential to those institutions permanently connected to the Internet. Depending on the network configuration, the router can be set up as a packet filter; usually, though, it is more convenient to set up a dedicated box to act as a firewall. Because they can be made extremely secure and have a low cost, Linux boxes can be very effective firewalls.

Deploying a firewall on the Linux kernels 2.2.x is done with ipchains, while iptables are used on the new 2.4.x kernels. How to set up the actual firewall is beyond the scope of this article; we refer the reader to the ipchains HOWTO for the 2.2.x kernels and to Paul “Rusty” Russell's Packet-Filtering HOWTO for the 2.4.x kernels. Both of them can be found on the Internet by using any search engine. But building the actual firewall is not enough; in order to offer tight security, a firewall needs to be monitored. In this article we explain how to build and use a web-based ipchains monitoring system called inside-control.

There are two main uses of a firewall monitoring system: to check that no malicious cracker is trying to wreak havoc in the internal LAN and to check that users inside the LAN are not abusing the internet service.

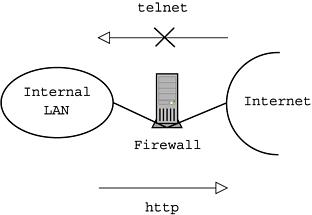

Here is a setup for a very simple firewall to which we will refer as a working example later in the article.

Suppose, for example, that the internal network is 10.0.1.0/255.255.255.0, the Linux gateway/firewall has the addresses 10.0.1.1 on the interface connected to the internal LAN and 10.200.200.1 on the interface connected to the Internet (both IP addresses are in fact nonroutable, so this is just a fictitious example). The first step to setting up a firewall is to enable gatewaying between the network interfaces:

echo 1 > /proc/sys/net/ipv4/ip_forward

We then proceed to build up a logging firewall using ipchains. First we flush all preceding rules, and we allow packets on the loopback interface and all ICMP packets:

ipchains -F ipchains -A input -i lo -j ACCEPT ipchains -A input -p ICMP -j ACCEPTNow we block and log the Telnet protocol from the Internet to the internal LAN:

ipchains -A input -p TCP -s 0.0.0.0/0 -d 10.0.1.0/24 23 -l -j DENYBut we allow and log the HTTP protocol from the internal LAN to the Internet:

ipchains -A input -p TCP -s 10.0.1.0/24 -d 0.0.0.0/0 80 -l -j ACCEPTFinally we set up permissive policies:

ipchains -P input ACCEPTThis firewall blocks and logs all incoming Telnet connections, it allows and logs all outgoing HTTP connections, and it allows everything else (see Figure 1). Such a setup is too permissive for serious protection, but it will illustrate well what the automated log scanning script can do.

Figure 1. Setup of Sample Firewall

The file the firewall outputs its logs to is usually either /var/log/syslog or /var/log/messages. In order to find out which one, you can do

grep -q "Packet log" /var/log/syslog && echo yes

If it outputs “yes” then it is /var/log/syslog, if it outputs nothing it is most probably /var/log/messages. You can confirm with

grep -q "Packet log" /var/log/messages && echo yesIf both commands produce no output, then the firewall is inactive or there was no logged traffic (in our example, Telnet and HTTP) through the firewall.

Regarding the 2.4.x kernels and iptables, things are a bit more complicated. First you must remember to compile the kernel with all of the packet-filtering options, including the LOG target. Second, change ipchains to iptables. Then change the names of the chains to uppercase (e.g., input becomes INPUT). Next, change the name of the targets (DENY becomes DROP). Lastly, specify port numbers in a different way. Listing 1 is the 2.4.x sequence of commands equivalent to the 2.2.x sequence of commands given above.

Let us now examine a sample log entry from our firewall's /var/log/syslog:

Jun 12 16:15:54 myfirewall kernel: Packet log: input DENY eth1 PROTO=6 212.65.214.2:34251 10.0.1.2:23 L=52 S=0x10 I=24016 F=0x4000 T=53 SYN (#38)

This means that at quarter past four in the afternoon on 12 June, the firewall (called, rather boringly, myfirewall) denied and logged a packet coming into its network interface eth1 (the external interface on the Internet) with the TCP protocol coming from 212.65.214.2 (from port 34251), directed to 10.0.1.2 (on port 23, i.e., the Telnet port) and having a length of 52 bytes. We shall skip most of the other details, apart from one: “SYN” means that the packet is the first packet of a connection. In practice, this information is very useful in discriminating those packets that are part of a pre-existing connection (that might have been initiated from the internal LAN) and those packets that attempt to establish a connection from the Internet towards the internal LAN. Usually one allows “reply” packets (which do not have the “SYN” flag set) but denies “SYN” packets because it means somebody out there is trying to make a connection to a computer in the internal LAN.

Of course, it is possible to check the status of a firewall by inspecting all relevant entries in the log file, but this is feasible if one logs only a few strange-looking packets. For example, on some firewalls I set up I decided to log all those packets coming from the Internet towards port 31337 on computers on the internal LAN, as 31337 is the default port BackOrifice uses. Whenever one is interested in getting some statistics from the firewall, it is likely that the size of the log file will be in excess of 5MB per day. In such cases, inspection of the log file by hand is no longer an option. This is when automated log scanning comes in.

When analyzing 2.4.x kernel firewall logs, the format is different:

Jun 12 16:15:54 myfirewall kernel: Packet log: IN=eth1 OUT= MAC=00:00:00:00:00:00:00:00:00:00:00:00:08:00 SRC=212.65.214.2 DST=10.0.1.2 LEN=52 TOS=0x10 PREC=0x00 TTL=64 ID=0 DF PROTO=TCP SPT=34251 DPT=23 WINDOW=11592 RES=0x00 SYN URGP=0

The fields we are interested in are SRC (source IP address), DST (destination IP address), SPT (source port), DPT (destination port) and the presence or absence of the SYN flag.

I am going to use Perl to build the log scanner. It is not the only option and, in fact, in order to achieve top performance one should use a compiled language. When I recoded this script in C++, I observed an execution speed gain of 100%.

The inside-control script is composed of a main parsing loop and an HTML data display loop. Since the script is a CGI it needs to reside on a web server configured for running CGI programs.

Note that the code, as described below, sacrifices functionality and useful details like error-checking for clarity. For example, there is no check that “opening a file” was successful before actually reading that file. Note also that the code below is customized to analyze the packet-logging format of kernels 2.2.x. Changing to the logging format of kernels 2.4.x, on the basis of the sample packet log described above, should be straightforward.

First, we open the log file and initialize some variables (those with Red Hat should use /var/log/messages instead of /var/log/syslog):

#!/usr/bin/perl open(LOGFILE, "/var/log/syslog"); $firstdate = ""; $date = ""; $total_traffic = 0;

Now we loop over each line in the log file:

while ( <LOGFILE> ) {

Skip all log entries which do not belong to the firewall:

next unless /Packet log/;We also parse the line (warning: in the Perl script, write the last line in this chunk as a whole long line, without the backslash):

chomp; @log = split; ($month,$day,$time,$policy,$proto,$ipsource,$ipdest, \ $tot_len) = @log[0,1,2,8,10,11,12,13];We then calculate the date and store the first date in the log. As we go on, we store the current date as the last date, so that after the last step the variable lastdate will contain the last date in the log:

$date = $day . " " . $month . " " . $time;

if (length($firstdate) == 0) {

$firstdate = $date;

}

$lastdate = $date;

Read the protocol type, the source IP address, the source port, the

destination IP address, the destination port and the packet length:

$proto = substr($proto, -1); ($ips, $ports) = split ":", $ipsource; ($ipd, $portd) = split ":", $ipdest; ($flush, $packetlen) = split "=", $tot_len;Now record the destination IP address in a string, and associate that string to the source IP address so that in the data display loop we will be able to loop over source IP addresses and retrieve the hosts they connected to:

unless ( $sourcedest{$ips} =~ /$ipd/ ) {

$sourcedest{$ips} = $sourcedest{$ips} . $ipd . " ";

}

We count the log entries for the source IP address:

++$source{$ips};

and sum up the total traffic volume:

$total_traffic += $packetlen;Finally, we sum up the per-host traffic volume:

$traffichost{$ips} += $packetlen;

}

Notice that not all the information gathered has been used (no talk

of ports, for example), so there is plenty of room for expansion

here.

First we display a nice-looking web page header, as shown in Listing 2.

Loop over the sorted source IP addresses and print the source IP address, the number of packets coming from that IP and the traffic (in bytes) generated from that IP:

for (sort keys %source) {

print "<TR><TD>$_</TD> ";

print "<TD>$source{$_} </TD>\n";

print "<TD>$traffichost{$_} bytes</TD>\n";

Now we are able to print the string containing the destination IP addresses contacted by the current source IP address:

$tmp1 = $sourcedest{$_};

if (length($tmp1) gt 0) {

print "<TD>\n";

@lt1 = split " ", $tmp1;

for(sort @lt1) {

printf "$_ <br>\n";

}

print " </TD>\n";

}

print " </TR>\n";

}

Finally, we print the HTML tail:

print "</TABLE>\n"; print "</center>\n"; print "</BODY></HTML>\n";

The version of inside-control I actually implemented is richer in functionality than the one presented here. You can download the script from www.iris-tech.net/hdsl-fw. Some of the main added features include the ability to display arbitrary names instead of IP addresses in the “Source IP” column. This is done with a very simple text database that maps IP numbers to names. The format is the same as the /etc/hosts file, and you can use that file if it is meaningfully configured for your internal LAN. The exact location of the “IP to names” database file can be specified by changing the relevant variable ($useripdb) at the beginning of the script.

There is also a search facility that allows one to look for a particular source IP address (or corresponding name found in the “IP to names” database) in the logs. The search form is displayed whenever the CGI is called without arguments from the browser. Arguments passing is done by the GET method.

Additionally, the main loop includes some data validation (the kernel cannot always log properly, especially on low RAM or low-spec CPUs) and some storage of port-dependent information.

Finally, the script can also be called without the web interface. Just pass any argument to inside-control, and all HTML output will be suppressed and some normal output will be provided instead. A search string for a source IP address (or its corresponding name found in the “IP to names” database) can be passed to the program via the -t option.

The purpose of this article is to explain some design principles and give some hints, not to give a prepackaged solution to log scanning problems. There are many areas where the inside-control script can be made better, such as performance and security. The following are some notes about inside-control, mostly related to security issues.

In order for a CGI to read the computer log files /var/log/syslog or /var/log/messages, these have to be made readable by all. This can be accomplished with the command chmod +r /var/log/syslog. This, however, is not very secure as it gives anybody on the system permission to read the computer log files. It would be much better to get the web server to run inside-control with a particular group permission, and then make the log files belong to that group.

After reading the article, one could conclude it is essential that a firewall also runs a web server, as inside-control needs to read the firewall log files. In fact, putting a web server on a firewall is very insecure: ideally a firewall should run no dæmon service, and all maintenance should be done at the console. When there is a need for remote administration, the only service that may be installed on the firewall is ssh, the secure shell. Running inside-control is still possible by setting up a separate web server within the internal network that also acts as a syslog server for the firewall.

Firewall logs can fill up a partition pretty quickly. In order to avoid having a clogged hard disk on the firewall (which could lead to a malfunctioning internet connection), depending on the amount of traffic you want to log, you have to allow for a large log file space. For high data volume services (typically HTTP, FTP, SMTP, NetBIOS, LPD and database services) I would advise setting up a second hard disk of at least 20GB in size, with just one partition mounted on /var/log. Also keep in mind that the script needs some error-checking code on critical steps like opening a file.

Finally, there is a lot of room for improvement everywhere in the script and especially in the main loop. One can use much more data from each log line than is discussed here. However, it is always a good idea to not show too many details; otherwise, the whole point of having an automated log scanner is defeated. If you display all available details, you end up having to look for suspicious entries in an unmanageably high volume of traffic log.