An exercise in porting Linux applications to Windows is made easier using GUI toolkits like GTK+.

Unfamiliar software has been a frequent excuse for Windows users not to switch to Linux. A lot of work is being done to undo this reasoning, not by bringing closed Microsoft software to Linux, but by bringing the benefits of open-source Linux software to Windows. Cross-platform versions of most popular Linux desktop applications are available today, including the GIMP image editor, StarOffice/OpenOffice office suite, the Mahogany e-mail client, the Amaya WYSIWYG Web Editor and many web browsers, including Mozilla and Opera. These all run on Linux and Windows, and some even support Macintosh.

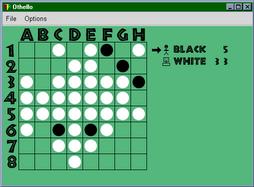

Robin (black) being clobbered by the Windows version of LinuxGothello in AI play.

Popular server applications like Apache and MySQL also have been ported to Windows, but most programmers consider porting desktop graphical user interface (GUI) software to be the most daunting task. There are tricks that can help, but we'll show that it's not that hard to accomplish. In this article we'll port Gothello, a Linux version of the game Othello, to Windows. In the process we'll learn something about programming GTK+ (also called GTK). Our code changes to Gothello will be made in such a way as not to break existing Linux code.

Othello, a cross between checkers and tic-tac-toe, is a popular game. Released in Japan in 1971, Othello is a variant of the game Reversi, invented in England in 1888. Although many open-source software versions of Othello exist for Linux, none of them would compile under Windows until now.

A quick search for Linux applications at Freshmeat.net reveals many open-source, Linux-only versions of Othello: Darwersi, Desdemona, Gothello, GReversi, QtHello, Rhino and xreversi. Choosing software based on a GUI with cross-platform support makes porting much easier. Both GTK+ and Qt are Windows-ready, but X11 is not (eliminating xreversi from our list). Fortunately, most modern Linux software is based on those two portable GUI libraries that form the underpinnings of GNOME and KDE, respectively. For our first Linux-to-Windows 2000 porting project we chose GTK+-based Gothello written in C.

Gothello author Osku Salerma is a computer science student at the University of Helsinki, where Linus Torvalds studied while creating Linux. Salerma says, “Gothello came about because I was interested in game trees. The AI is implemented using Negamax search with Alpha-Beta pruning and Iterative Deepening.” Gothello uses AI to provide a virtual opponent in the game. Salerma plans to work in UNIX systems programming after he graduates in a year or so.

GTK+ (GIMP Toolkit) is a popular library for creating graphical user interfaces in C or C++. Under the LGPL you can develop open software, free software or commercial software using GTK+. Although originally written for developing GIMP, GTK+ is used in a large number of software projects, including GNOME. GTK+ is built on top of GDK (GIMP Drawing Kit), a portable wrapper for platform-specific windowing APIs like Xlib and Win32. The primary authors of GTK+ are Peter Mattis, Spencer Kimball and Josh MacDonald.

Tor Lillqvist, an engineer at Tellabs in Finland, ported GTK+ and GIMP to Windows in 1997. Lillqvist says he ported GIMP for fun so he could use it with his Minolta slide scanner in Windows. Although the current release of his Windows port, version 1.3.0, is from December 2000, there is a lively developers list in which Lillqvist actively takes part. “I am still working on it as much as time permits”, says Lillqvist. “I am the father of a three-month-old baby girl.”

Before attempting to build Gothello on Windows, we need to download and install the necessary GTK+ Windows libraries. A link to GTK+ for Win32 is provided on the main GTK+ web site. Download and unzip the glib, libiconv, gtk+ and extralibs files. The lib files are prebuilt, so there's no need to remake them. Where you place the files is a matter of personal preference, but we like /code/lib/gtk. We'll download Gothello and untar it in /code/oss/gothello. Note that Windows, except at the DOS command prompt, supports forward slashes in all file paths. Avoiding Windows-only back slashes saves trouble when switching back and forth with Linux.

Many books are available on GTK+ programming. We have GTK+/Gnome Application Development by Havoc Pennington (New Riders, ISBN 0-7357-0078-8). A book isn't required, however, because the GTK+ web site provides a nice on-line tutorial maintained by Tony Gale. We'll use his “Hello World” code example to test that we have GTK+ properly installed [Listing 1, available at ftp.linuxjournal.com/pub/lj/listings/issue93/5574.tgz]. The heavily commented code is a good introduction to how GTK+ works.

Open-source purists may prefer choosing an open-source Windows C++ compiler, and that is certainly feasible. Dev-C++ is a full-featured, open-source Windows integrated development environment (IDE) that we've used successfully in the past. This compiler incorporates the MinGW or Cygwin (gcc) compilers and the Insight or GDB debuggers. Most Windows C++ programmers, however, use the popular Microsoft Visual C++ compiler. It doesn't matter which Windows compiler is used, but we'll select Visual C++ so that we can cover some pitfalls that often trap less-experienced VC++ programmers. If you are a Linux open-source project leader accustomed to working with gcc, these VC++ tips can save you a lot of aggravation when working with the Windows VC++ programmers porting your code.

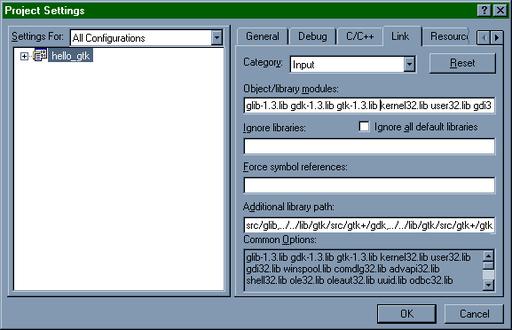

The deceptively simple Visual C++ project settings dialog, estimated to have more potential configurations than there are atoms in the universe.

Although VC++ can use Makefiles, smooth handling of project files is one of its most popular features. Project files are generated automatically by VC++. The typical VC++ programmer has no clue how to write a Makefile. Project files consist of a workspace file (extension .dsw) and one or more project files (extension .dsp). These text files are written by the {Project}{Settings} tabbed dialog box and are not intended for editing by hand—there's a zillion setting combinations. Not knowing what to look for here is one of the hardest aspects facing a user unfamiliar with VC++. A few settings are critical. Note that simply because a project will build doesn't mean the settings are right.

Now we come to the heart of setting up a complex VC++ project. Listen carefully because even though you may never use VC++ yourself, you almost certainly will have to tell any member of your team doing a Windows port how to set it up correctly. What VC++ programmers typically do is set absolute paths to libraries in the project or configure their copy of VC++ to search implicitly for libraries where they have installed them. That would make the project files fail for anyone other than the person doing the port—not cool.

Here's how to set relative paths in the project from {Project}{Settings} in VC++:

{C/C++}{Preprocessor}{Additional include directories}:

../../lib/gtk/src/gtk+,../../lib/gtk/src/glib,

../../lib/gtk/src/gtk+/gdk

{C/C++}{Use runtime library}:

Multi-threaded

{Link}{Input}{Object/library modules}:

glib-1.3.lib gdk-1.3.lib gtk-1.3.lib

(added before the others here)

{Link}{Input}{Additional library path}:

../../lib/gtk/src/glib,../../lib/gtk/src/gtk+

/gdk,../../lib/gtk/src/gtk+/gtk

Make sure that All Configurations is selected before entering these settings, or else after you get the Debug version to build you'll have to do it over again with Release settings. Since GUI applications typically are multithreaded, it is always prudent to turn that on.

Our hello_gtk project will build now, but it won't run. A Windows error message complains that we haven't installed the GTK+ dll files (dynamic link libraries). Copy these to the Windows system32 folder, or better still, create a new folder for them and set Windows {Control Panel}{System}{Advanced}{Environmental Variables}{Path}. (Note: path changes won't take effect in the VC++ debugger without restarting VC++.)

After all this work to get VC++ and Windows configured properly, the Gothello porting effort itself isn't so hard. The first step is to deal with build errors from missing UNIX include files that don't exist under Windows, such as <sys/time.h> and <unistd.h>. Fortunately, most of the functions and type definitions included in these missing files are available somewhere in Windows. It's a bit of an Easter-egg hunt to find the right Windows header file. Some are documented and easily found, others are not. It turns out that <winsock.h> is a good place to look for undocumented, UNIX-compatible Windows calls. Berkeley sockets incorporate many common UNIX types and were implemented as part of Windows sockets.

Building and running the GTK+ “Hello World” test application proves that GTK+ is installed correctly.

Code revisions to Gothello's timer.h include:

#ifdef _WIN32 #include <winsock.h> #else #include <sys/time.h> #include <unistd.h> #endif

Windows compilers implicitly define the system variable _WIN32. Using that name as a conditional is the standard method of making code automatically sense whether it is being compiled under Windows or some other operating system. This allows us to keep good Linux code in place while substituting Windows-specific code where needed.

Fixing Gothello's timer.c is a little more difficult because we encounter a UNIX function not implemented anywhere in Windows:

#ifdef _WIN32

#include <sys/timeb.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <winsock.h>

void gettimeofday(struct timeval* t,void* timezone)

{ struct _timeb timebuffer;

_ftime( &timebuffer );

t->tv_sec=timebuffer.time;

t->tv_usec=1000*timebuffer.millitm;

}

#endif

Having a copy of Using C on the UNIX System by David Curry (O'Reilly & Associates, ISBN 0-937175-23-4) comes in handy to tell us what the gettimeofday() function is supposed to do.

Code revisions to Gothello's child.c include:

#ifdef _WIN32 #include <stddef.h> #include <io.h> #include <stdlib.h> #include <winsock.h> #include <stdio.h> #else #include <sys/time.h> #include <unistd.h> #endif

Making child.c compile wasn't hard. We just had to track down the relevant Windows include files when the compiler complained about size_t, timeval, fd_set, FD_ZERO, FD_SET, tv_sec, tv_usec, select, NULL and _exit.

Code revisions to Gothello's gtk_main.c include:

#ifdef _WIN32 #include <io.h> #include <fcntl.h> #include <process.h> #else #include <unistd.h> #endif

It isn't until the body of gtk_main.c that we break a sweat. Windows doesn't fork(), and that can be a big problem in porting Linux applications. With fork(), Linux creates a clone of the running program in memory that can then branch to perform a simultaneous task. Windows has the less-powerful spawn() function but prefers to do its multitasking with threads. We'll rewire Gothello's main() to make it think that a Windows thread is a child process. Gothello uses pipes to communicate between parent and child processes, a standard approach. Pipes work in Windows threads, too.

Explaining this thread (Windows) and fork (Linux) code in detail would be too tedious, but the design is based on the simple idea of creating two thread functions containing the code that the child and parent processes each would execute after forking. Be careful not to put the gtk_main() message pump loop function into these threads; doing so would stall the Windows message queue and lock up the application. If you are designing a Linux project with porting in mind, you can save yourself some trouble by using threads from the beginning. Linux threads are similar to those found in Windows.

The code in Listing 2 [available at ftp.linuxjournal.com/pub/lj/listings/issue93/5574.tgz] is much easier to understand if you read the functions in reverse order. The code in read_thread() requires some special explanation. Inside Gothello init_all() we make this minor modification, commenting out gdk_input_add() in Windows:

#ifndef _WIN32

gdk_input_add(to_parent[0], GDK_INPUT_READ,

read_from_child, NULL);

#endif

When we first tried to run Gothello under Windows, the program locked up. The Windows port of GTK+ doesn't seem to be happy with gdk_input_add(). Threads are a better way to go than multitasking in the message loop. Instead of using gdk_input_add() to detect input on a pipe inside the GTK+ message queue, we handle that as an independently running, simultaneous thread. We also make a minor change to child.c to fake out the select() call that in Linux sets the pipe to operate asynchronously:

#ifdef _WIN32

ret = 0;

#else

ret = select(to_child + 1, &set, NULL, NULL, &tv);

#endif

Porting Gothello was our first time using

GTK+. It would have been easier to do the port had we first built

Gothello under Linux. We didn't do that

because we wanted to evaluate how hard it would be for a Windows

programmer unfamiliar with GTK+ to do a port sight unseen. It took

myself and partner Gabrielle Pantera a couple of weeks, working

part-time during nights and weekends. That popular Linux GUI

toolkits such as GTK+ and Qt are portable vastly simplifies the

task of making Linux applications run on Windows.

Ported Linux desktop GUI applications can ease the learning curve of Windows users considering a move to Linux. And Linux users can access their favorite applications when using a Windows machine that may be at the office or that belongs to a friend. You even can program enhancements to your favorite open-source application for Linux while working in another operating system. Besides, there's nothing wrong with easing a million Windows C++ programmers into open-source programming.