Howard provides an introduction to Cystal Space, and open-source alternative to commercial 3-D graphics engines.

Want to make a 3-D graphics game or application? First, you will need a 3-D graphics software engine on which to build it. Traditionally, your choices have been limited to programming your own from scratch or paying a high licensing fee to use another company's, which can restrict what you do with your final product commercially.

However, a third alternative exists: Crystal Space, an open-source 3-D graphics engine created by 31-year-old Belgian programmer, Jorrit Tyberghein.

An Indoor Environment Rendered with Crystal Space

Tyberghein created Crystal Space in 1997 after seeing games like Doom and Quake and wondering how they were made. With no prior experience in graphics coding, he researched the Internet on 3-D graphics programming and put together the first version of Crystal Space in two months. Tyberghein released the code as open source, and the Crystal Space development community soon was born. The graphics engine has since been ported from its original Linux code to UNIX, Windows 32-bit and NT and other OSes.

Most of the software currently being made with Crystal Space are role-playing games. The fact that the engine includes full control of one or more camera perspectives and has built-in support for networking makes it easier to develop multiplayer games, like role players. There are also flight simulators, real-time strategy games and first-person shooters, similar to Doom or Quake, under development using the engine.

As for how Crystal Space compares to commercial 3-D graphics engines, specifically those that power games like Quake III and Unreal Tournament, presently it is comparable in terms of specific graphics features but not in regard to code readiness and performance speed. But in general, Crystal Space is much richer because it is not just a game-specific engine. It is also a general-purpose graphics API, and it is being put to use to drive applications like a multimedia internet browser, a sound-editing program and an image viewer.

Andrew Zabolotny, a 28-year-old programmer from St. Petersburg, Russia, who has been contributing to Crystal Space's high-level coding says: “We have lots of things Quake or Unreal will never need because a first-person shooter is a very specific type of game that needs just a limited set of features.”

Developers who have been working with Crystal Space cite the engine's stability (it rarely crashes) and the completeness of its 3-D-rendering features as reasons for using it and contributing to its development.

Yet how necessary is a 3-D graphics engine these days, considering the advanced and powerful 3-D graphics chipsets that have become a standard feature in most PCs? The simple answer is that even with the best 3-D technology, you still need a software engine to manage what the hardware is doing.

“There is always a limit to what hardware can do”, says Tyberghein, Crystal Space's creator. “Even the best hardware cannot handle millions or more polygons just by rendering them all. So an engine still has to do some optimization to limit what is sent to the hardware.”

For example, a software engine like Crystal Space is needed to determine quickly which parts of a game's virtual environment are visible to the user. This helps to maximize the performance of the 3-D chipset by not wasting its resources in making it render an object that will not actually appear on the monitor, even if it is supposed to exist (though off-camera, away from the user's point of view) within the virtual environment.

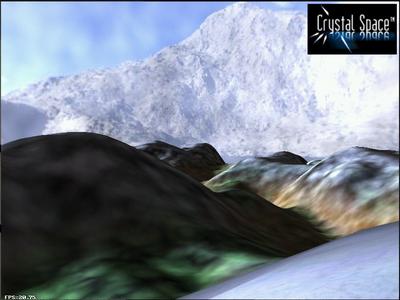

Example Environment Created with Crystal Space's Landscape

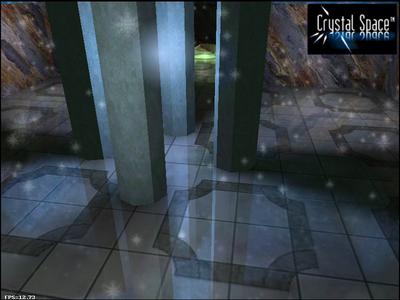

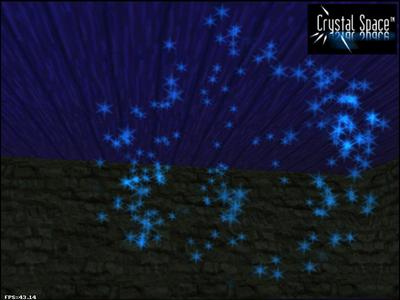

Crystal Space is free under LGPL. This 3-D game development kit written in C++ supports numerous graphics features and fancy effects: true six degrees of freedom; colored lighting; mipmapping; portals; mirrors; alpha transparency; reflective surfaces; frame-based and skeletal-animated 3-D sprites; procedural textures; radiosity; particle systems; halos; volumetric fog; scripting using Python or other languages; 8-bit, 16-bit and 32-bit display support; Direct3D, OpenGL and software graphics rendering; font support; and hierarchical transformations, to list only a few.

Although it cannot match graphics engines like Quake III's or Unreal Tournament's in performance, Crystal Space has its own advantages over them: for one, it is cross-platform, so you can write code that will run equally well on Linux, UNIX, Windows 32-bit, Windows NT and seven other OSes to which the engine has been ported.

Crystal Space has a flexible plugin system so that a single executable works with various renderers like OpenGL, Direct3D and Glide. Since the first release of the engine, the OpenGL renderer in particular has been rewritten and runs a lot faster than in its previous incarnation.

A Starship Flying toward Earth in a Scene Rendered in Real Time

Also important is that Crystal Space can read many 3-D graphics file formats automatically. There are several importers supporting various 3-D formats (such as 3DS, OBJ, MDL, MD2, LWO and ASE). Inversely, the engine has a set of Python scripts so that environments and models can be exported to Crystal Space from within Blender.

Although the primary purpose of the engine is to produce 3-D graphics, it even has a 2-D API to go along with its 3-D API. “I wrote a full-blown windowing GUI based entirely on the Crystal Space low-level API”, says Zabolotny.

Pieces of separate code even can be used outside of Crystal Space in projects unrelated to game or multimedia development. These include a csIniFile class (for .ini file management), an SCF (shared class facility) subsystem, a csArchive class (which deals with .zip files) and a VFS (virtual filesystem) subsystem.

The most significant weakness of Crystal Space is its lack of good collision detection programming. Thomas Hieber, who has been developing Crystal Shooter, a first-person shooter, with Crystal Space, has been spending most of his time improving the engine's capabilities in this area. “There is some support in it, but it is not very useful for games”, says the 30-year-old software engineer from Germany. “There is only static testing of object-against-object that basically will return information about where the collision occurs, if any. But there is no good support for fast-moving objects.”

Another complicated issue is how Crystal Space handles lighting. It supports colored static and dynamic lighting with soft shadows, but getting these to work fast under all possible game processing circumstances is a challenge and one which Crystal Space currently does not totally meet.

Snow Falling over a Shiny Floor Demonstrating Crystal Space's

The Crystal Space community definitely needs programmers to contribute. Tyberghein is looking for people who are skilled in programming graphic engine internals and adept in algorithmic thinking—essentially those who can help fine-tune the performance of the core engine itself. “I have lots of people helping on the other parts of Crystal Space (i.e., OpenGL and Direct3D programming, Windows and Linux porting) but very few people are capable of helping me with the engine”, he says.

“If we had more good programmers, we could do much more”, Zabolotny says. “We primarily need people skilled in cross-platform C/C++ programming.”

As of this writing, the primary goal for the Crystal Space team is achieving API-stability. “Our development version is now rather stable, but there are still a few things to do”, says Tyberghein. The current release of Crystal Space, 0.90, serves as a predecessor to the long-awaited 1.0 release. The API between 0.90 and 1.0 should be nearly the same, but the release of 0.90 is meant to facilitate bug hunting and documentation writing.

One of the enhancements in 0.90 being tested is a revamped landscape-rendering engine that is more tightly and better integrated within Crystal Space's code than it was in previous versions. There are several new special effects that the graphics engine can draw, like hazes and lens flares, and there is the addition of a particle-rendering system. On a technical level, Crystal Space's tools have been made much more modular and simpler to access. More plugins and code, which were previously available in separate libraries, have been incorporated.

Ultimately, could Crystal Space ever evolve to the point where it has what it takes for commercial game development and become as widely used as proprietary 3-D graphics engines? Even Tyberghein expresses doubts:

If you license the Quake III engine, then you're sure to get a quality product that will work. So if you want technical support, you should not use a free engine. However, if you feel like you can cope with the lack of support, or if funding is a problem, then an open-source engine is for you.

Stars Rendered with Crystal Space's Particle Animation System

Hieber concedes that “Crystal Space is miles away from Quake III”, but he does not believe this will hinder anyone from making great games with Crystal Space. It is, after all, well designed, though it doesn't necessarily have powerful technologies, which affect the quality of games. “Look at Tomb Raider or Half-Life”, he points out. “Neither has a really great 3-D engine, but they all have been successful because of the value of their game play.”

Visit the Crystal Space site at crystal.sourceforge.net.