Use Linux to visit virtual consoles, cities and battle zones.

François, what are you looking for on Freshmeat? Quoi? A program to digitize you so you can go inside the computer? Yes, I know what it looks like in the movies, but virtual reality hasn't quite made it there yet. I thought you understood that when we discussed lightcycles months ago. No, François, I don't think people are going to be living inside computers anytime soon. I'm not laughing at you, mon ami. I am just amused, that's all. No, I'm sorry to disappoint you, but I don't think there are cities or people in your Linux system either. We will discuss this later. Our guests will be here any moment, and we must be ready for them.

What did you say, mon ami? They are already here? Quickly, François, help our guests to their tables. Welcome, everyone, to Chez Marcel, where fine wine meets exceptional Linux fare and the most superb clientele. When you have finished seating our guests, François, head down to the wine cellar and bring back the 2002 Ctôes du Roussillon Villages.

François and I were just discussing the possibility of virtual worlds inside our computers, a truly amazing prospect but one that is still fantasy. It's true that amazing things have happened in the time I've been working with computers. Your Linux system is one of those things, and its open nature means a freedom to explore that simply doesn't exist elsewhere. Still, I keep thinking that the computing model in general is still in its infancy. Maybe it's because I watched too much science fiction and as a result, my expectations are a bit high. Think back to the movie Tron, for instance. In the opening sequence, Flynn the hero of the show, sends a program named CLU into the system to locate some missing files. CLU, the program, looks like Flynn and moves around in a 3-D tank while a companion bit offers yes or no advice. There are towering skyscraper-like structures all around as he navigates his tank down digital streets. That's the virtual computer world I wanted to experience in my younger days.

Ah, François, you have returned with the wine. Please, pour for our guests. May I suggest, mes amis, that you enjoy the many hidden flavors in this excellent red.

Although there may be no hidden worlds inside the system, plenty of things are otherwise hidden from view. Virtual consoles, for instance, scroll information that is hidden from view once your graphical desktop starts up. Sure, you could jump out of your graphical session with a Ctrl-Alt-F1 to see what is happening out there, but there is a better way. To view the hidden contents of that virtual console, type the following at a shell prompt (you will need root permissions for this):

cat /dev/vcs1

You see, what you may not know is that your system keeps track of the contents of those virtual consoles (1-6) in a special device file, /dev/sdaX, where X is the number of your virtual console. For example, here is a sample of the output of the first VT on my Ubuntu test system:

* Starting OpenBSD Secure Shell server... [ ok ] * Starting Bluetooth services... hcid sdpd [ ok ] * Starting RAID monitoring services... [ ok ] * Starting anac(h)ronistic cron: anacron [ ok ] * Starting deferred execution scheduler... [ ok ] * Starting periodic command scheduler... [ ok ] * Checking battery state... [ ok ] * Starting TiMidity++ ALSA midi emulation... [ ok ] Ubuntu 6.04 "Dapper Drake" Development Branch francois tty1

This is interesting stuff, but it hardly qualifies as a hidden world, and it just doesn't have the Wow! factor my humble waiter is looking for. Yet, despite what I said to François, there are ways to see cities inside your Linux system. It's a bit of a stretch, but some fascinating visualization programs exist—experimental in nature—that try to create a real-world view of the virtual world of processes, memory and, of course, programs. One of these is Rudolf Hersen's ps3 (see the on-line Resources), and to take full advantage of ps3, you need a 3-D video card with acceleration.

Compiling the program is fairly simple, but it does require that you have the SDL development libraries:

tar -xjvf ps3-0.3.0.tar.bz2 cd ps3-0.3.0 make

To run the program, type ./ps3 from the same directory, and you should see a 3-D representation of your process table. When it starts, you may get something other than an ideal view, but that's the whole point of ps3. You can rotate the views in all three axes and look at the process table from above or below. If the processes are too high at the beginning, simply scale them down to something more reasonable. Each process is identified by its program name and its process ID.

Navigating the ps3 display is done entirely with the mouse. Click the left-mouse button and drag to rotate and adjust the height and speed of horizontal rotation. Click and and drag using the right-mouse button to rotate the view horizontally and vertically. The wheel on your mouse lets you zoom in and out. To quit the ps3 viewer, press the letter Q on the keyboard.

ps3 is in no way a scientifically accurate means of viewing system processes, but it is enlightening and entertaining. So now we have virtual buildings and the makings of a virtual city somewhere inside your system. All we're missing now are tanks. Well, I may have an answer to that one as well. It's called BZFlag, and this certainly calls for François to refill our glasses. Mon ami, if you please.

BZFlag is a multiplayer 3-D tank battle game you can play with others across the Internet (Tim Riker is the current maintainer of BZFlag, but the original author is Chris Schoeneman). The name, BZFlag, actually stands for Battle Zone capture Flag. It is, in essence, a capture-the-flag game. To get in on the action, look no further than your distribution's CDs for starters. BZFlag's popularity means it is often included with distros. Should you want to run the latest and greatest version, however, visit the BZFlag site (see Resources). You'll find binaries, source and even packages for other operating systems. That way, you can get everyone in on the action.

Unless you specify otherwise, BZFlag starts in full-screen mode, but you can override this by starting the program with the -window option. The game begins at the Join Game screen. Before finding a server (the first option on the screen), you may want to change your Callsign (or nickname). We'll look at some of these other options after we've selected a server. For now, move your cursor to the Find Server label and press Enter.

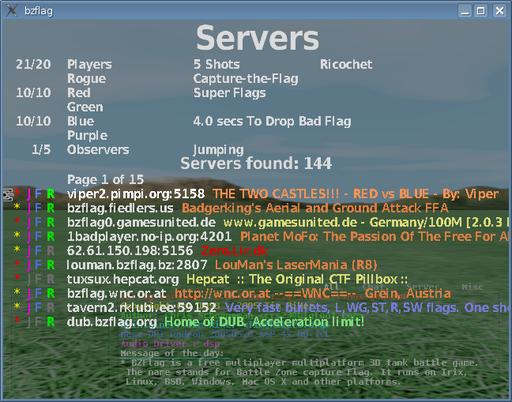

You won't have any trouble finding people to play with—you'll get a list of dozens of servers currently hosting games (Figure 2). Scroll down the list of names to find one that suits you. Your criteria might be the number of players, how busy a server is or how many teams are involved. When you look at the server list, make sure you pay attention to the type of game being hosted on the server. Some have team-oriented capture-the-flag play, and others host free-style action. You also may be limited by the number of shots at your disposal, so aim carefully.

Figure 2. At any given time, dozens of BZFlag servers are running worldwide and hundreds of people are playing.

When you have made your choice, press Enter, and you'll find yourself back at the Join screen (Figure 3) with a server selected. You could simply start the game, but you may want to fine-tune a few more things before you start up your tank. Cursor down to the Team label, and press your left or right arrow keys. By default, you will be assigned to a team automatically, but you can change that here if you prefer. One of the roles you can play instead of joining a team is that of Observer. This is not a bad idea if you are new to the game, because it lets you watch how others are handling themselves.

The Join screen also lets you enter the name of a server manually, rather than search for it. This is useful for hosting private games on a local LAN. Speaking of hosting games, I'm sure you noticed the Start Server option at the bottom of that list. Let's go ahead and join the game. Scroll back up to Connect and press Enter.

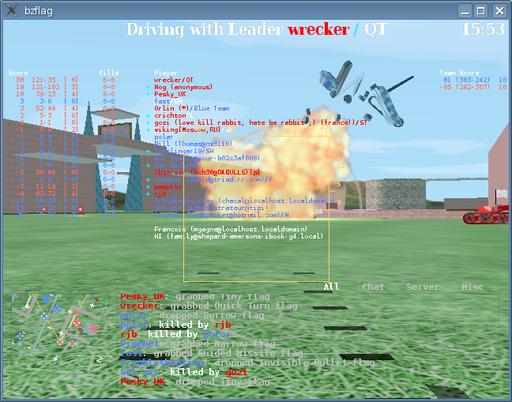

I hope you are ready, mes amis, because the action starts immediately, and some of these players are, well, seasoned. Move your tank using your mouse, and fire by clicking with the left-mouse button. These tanks are highly maneuverable and even can jump in some games (you do this by pressing the Tab key). To learn all the keystrokes, by the way, press Esc at any time, and select Help. During play, BZFlag provides an extensive heads-up display with stats on players, kills, personal scores, team scores and more (Figure 4). Keep an eye on the map to your lower left, as it can alert you to enemy tanks. If you can drive, fire and type at the same time, press N to send a chat message to the group, or M to send one only to your teammates. If you see the boss coming, press F12 to exit the game in a hurry. Just a little joke, mes amis. I would never suggest that you play this at work.

Figure 4. The action is fast and tense, with tanks blowing up everywhere you turn. Be careful not to be one of them.

The hour is getting late, mes amis, but I don't want to leave you with the impression that all the virtual worlds that may exist in our systems are built entirely on destruction and mayhem. You can, in fact, build an entire civilization, including a city, its farms, factories, markets and every other trapping of modern (or premodern) civilization. Download Lincity (or check your distribution CDs) and start building. The idea of this highly addictive and time-consuming game is for you to build a city, and in the process, feed and clothe your people, and create jobs so you can build and sustain an economy. Invest in renewable energy as you strive to build a civic Utopia (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Lincity is a computerized city simulation that makes you wonder why creating a Utopia is so darn difficult.

As things get better and better, you can save your game and get back to creating this ideal world of yours. Okay, you're right, it's not as easy at it sounds. The clock is ticking, and the months go by fast. Without careful attention, your world may wither away in its own poisons. I should warn you that starting from scratch may be a bit of a confidence destroyer. Why not start when things are good? When the game begins, click the Menu button in the upper left. The main window then provides you with some choices, including one to Load a saved game. The game comes with two: one is called Good Times and the other (you guessed it), Bad Times. I recommend Good Times to get your virtual flippers wet. When you get so good at this that you feel you can fix anything, go for the Bad Times, and see if you can pull your city back from being $25 million in debt.

The clock, mes amis, it is telling us that closing time is upon us. With all these sounds of artillery and explosions coming from your workstations, it seems obvious that we will have to stay open just a little longer. François will happily refill your glasses one final time before we say, “Au revoir”. The games may be all virtual, but the wine is real. It's a good thing too, but I'd hate to have it spilled every time someone fired a shot. On that note, please raise your glasses, mes amis, and let us all drink to one another's health. A votre santé Bon appétit!

Resources for this article: /article/8882.