Video editing in Linux can be hell, but a handful of programs are showing the way forward to a better world.

In the January 2006 issue of LJ, I wrote an extensive article surveying the state of the art in video production software on Linux. At the time, there were a lot of new players, some brought into the field from the first Google Summer of Code, and very few of them were serviceable all the way around.

The intervening years have done their Darwinian work, with some projects maturing rapidly, others stagnating and others being abandoned or disappearing off the Net altogether. But, as Nietzsche noted (or would have if he were as interested in software as he was in philosophy), “What doesn't kill a project, makes it stronger.” This article is about the survivors. Few though they are, some have managed to thrive.

Video editing on Linux always has been curiously bifurcated. On the one hand, there are glorious high-end finishing packages, such as Discreet Smoke, that are used routinely on big-budget productions, but the price tag for a single Smoke system runs into the tens of thousands of dollars, so it's not particularly budget-friendly. On the other hand, there are excellent low-end packages, such as Kino, which handles DV with grace, speed and polish. The middle ground between them is littered with half-finished projects, failed projects and Cinelerra, a behemoth that is both finished and polished but can be said to “work” only in the sense that a horse with five legs might learn how to walk.

That is changing.

There is nothing, in theory, stopping an open-source video editor from offering the basic functionality of a Premier or a Final Cut Pro, together with the switching ability of a product like Casablanca to produce very quick edits of multicamera shoots. Cuisine, in fact, was developed with this ability in mind, and even though it got only halfway there before it was abandoned, several of the innovations it used toward that end could be instructive. Some of the projects here already are well on that road.

The Linux multitrack field is now dominated by three programs that have been going gangbusters on development. All of them are not only still standing but also are proceeding at a meteoric pace—and in a promising direction: Jason Wood's KDENLIVE, Richard Spindler's OpenMovieEditor and The Blender Foundation's Blender.

KDENLIVE (the KDE Non-LInear Video Editor) is the project that has garnered the bulk of my ink thus far (I reviewed it in-depth in the September 2007 issue of LJ), mostly because it has been a clear leader for quite a long time. It was the first multitrack in the current crop to attain usability.

Pioneered by Jason Wood and now maintained by a team of developers, KDENLIVE is a Qt-based editor that uses FFmpeg as its decoding engine and Dan Dennedy's MLT as its frameserver and EDL backbone. It's a powerful combination, putting it into a position to handle HD as easily as garden-variety DV, and opening up its importable profile to include pretty much any video format you can watch on a Linux box.

The interface is laid out much like that of the late MainActor. It's familiar and easy to pick up, and if you're like me and really hate this paradigm, you can undock the interface components and reconfigure them until your picky little heart is content.

The underlying MLT framework supports infinite audio and video tracks, and there are a healthy number of built-in video and audio effects (although extensive keyframing remains problematic at the time of this writing). Its interface sluggishness mentioned in my prior review largely has been solved, as have the difficulties working with interlaced footage when scaling. The titler subsystem now works and is very nicely compatible with installed TrueType fonts and a wide variety of raster graphics formats.

All of this is great, but it doesn't amount to a hill of beans in this crazy world if it can't perform. That's where the drawbacks show up. It's still fairly crash-prone, and the current migration from FFmpeg as the frameserver to MLT has broken a few things relating to a/v synchronization with NTSC footage. These are known issues due to MLT bugs, which are, at the time of this writing, being fixed (and hopefully will be fixed by the time you read this).

There is still a way to go in a couple of areas. Its audio toolkit is rudimentary, but its easy exporting dialogue-splitting means you can split the audio and push it over to Audacity or Ardour for sweetening once your edit is done.

The export GUI also presents a problem. As extensive as it is, it isn't friendly for creating new profiles, which means that you have to hand-tweak scripts or wait for new profiles if you want one that doesn't happen to come prepackaged. Fortunately, the plethora of profiles is quite staggering, including a wide range conforming to all the current HD broadcast standards.

The final weakness—and the most annoying to me personally—is KDENLIVE's lack of support for importing image sequences. It's something that should be axiomatic in a system using FFmpeg as a back end, as FFmpeg is an excellent manipulator of image sequences and Bash has wild cards for such things built in. This alone bumps KDENLIVE out of the professional space, but with this exception, it is a highly promising work in progress, stable enough to use so long as you don't mind pressing Ctrl-S fairly frequently. Its most irritating issues are pretty much solved, and I've used it to complete several short and long-form projects. It's perfectly serviceable for day-to-day use if you know your way around your footage.

KDENLIVE is the only product in this roundup that supports video capture.

Here's hoping the development team keeps up the excellent work!

OpenMovieEditor is the brainchild and personal hobby of Richard Spindler, and it's generally stable, fast and usable. It supports the full range of framerates and allows for the creation of pretty much any working profile, and it sits partly—though by no means exclusively—on FFmpeg with all the glorious format compatibility that this implies.

Figure 2. OpenMovieEditor's FLTK interface: the editing tools are all embedded right in the interface next to the tracks, and the nodes editor for the compositing subsystem is visible at bottom left.

The work flow is pretty much what you'd expect, with the interface closely mirroring what we've come to expect from KDENLIVE and similar projects. Unlike KDENLIVE, the interface is not easily reconfigurable. However, because it's built on FLTK, it's fairly rock-solid. It doesn't crash, it's fast and light and doesn't bog down due to fancy widget rendering. The resulting look is fairly inhospitable cosmetically, but you don't need rounded corners and crystalline widgets when you have a program that stays up like a truck and speeds along like a Trans Am.

HD compatibility is no problem; OpenMovieEditor is profile-agnostic. If FFmpeg or libquicktime can read it, you can use it, and it's always obvious what's compatible because it shows up with a thumbnail in the media browser tab.

The development philosophy under which Spindler has proceeded leverages the power of the Open Source world to his project's advantage. When I interviewed him for background for this article, he told me that, behind the scenes, he is involved in several external video projects that he uses to advance OpenMovieEditor, building on a suite of highly stable external libraries: gavl, libquicktime, the Frei0r plugin API, JACK and several others. All of these things extend the package considerably, with Frei0r being of special note as the primary source for the video effects. Spindler himself is involved in Frei0r, libquicktime and Cinelerra development in varying degrees, which gives him the familiarity he uses to integrate their best tricks into his own project.

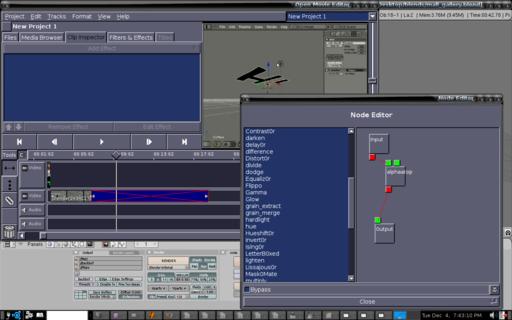

He has used it to stunning effect. The audio and video effects in OpenMovieEditor work splendidly, although many of them could use more settings controls to move them into a more professional realm. The latest addition to his bag of tricks though is a major step in the right direction and something hereto unheard-of in the realm of open-source video editing packages: nodes-based compositing, which can use all the installed video effects (although Blender also has a nodes-based compositor, its interface with the video editor is oblique and patterned more after the fashion of a finishing system than a video editor).

OpenMovieEditor is unique among Linux multitrack editors in that it is capable of running its audio through the JACK Audio Connection Kit (JACK). This gives it access to all the excellent, readily available Linux pro-audio tools, and with proper kernel patching it works in real time. The upshot is that you can use OpenMovieEditor as part of a sync chain that will allow you to create, compose and tweak your soundtrack while always seeing the video and hearing the audio as it's mixed. It's hard to overstate the power of this; it is unambiguously a professional feature, and it's a great benefit to independent filmmakers and small studios who need the performance it offers and aren't able to buy the higher-end turnkey systems on offer for the film industry. But Spindler isn't done—he and his community members are working on integrating the system with Inkscape and with Blender for generating new transitions and other effects. The future on this seems bright!

When it comes to asset management, the program seems, at first glance, not much different from KDENLIVE. Looks are deceiving though—it's much more flexible. When it comes to open-source projects, OpenMovieEditor's asset management system, which allows clips to be stored in a bin off the timeline for grabbing and inserting, is a work-flow tweak that makes shot selection independent of the status of the edit, and also makes assembling the selected shots far quicker. With its ability to set clips in the use bin rather than whole files, its ability to use image sequences and its thumbnail filesystem browsing, it is far above par, and much more sensible than what's available for asset management in KDENLIVE or Blender.

One caveat that Spindler gave me when I interviewed him via e-mail:

OpenMovieEditor is very much a work in progress; this means that it is not yet feature-complete, but that it has a rapid pace of changes; development is happening rather fast, and not in a very “controlled” fashion. So, it might happen that stuff that worked once can break, or that new features are not as well tested as they should be.

So, it's a wise procedure, when upgrading OpenMovieEditor, to test fresh compiles thoroughly before installing them, or at least to keep around an older package you know to be working to revert to should there be problems.

In sum, OpenMovieEditor is an excellent package all around and well worth the time investment in learning it. It lacks the plethora of export profiles offered by KDENLIVE, but it makes up for this with a well-appointed, intuitive GUI that allows experienced editors to specify their own export settings for pretty much any destination or mastering format supported anywhere under Linux. It goes further, supporting high bit-depth editing, effects and export with integrated (though still primitive) nodes-based compositing. This is a project with nowhere to go but up.

Blender is justly and primarily famous for its standing as the premier free/open-source 3-D graphics package, but that's not all it can do. Because it is intended as an end-to-end finishing system for animation, it has integrated a full-featured, OpenGL-driven video editor called the VSE (Video Sequence Editor).

Figure 3. Blender comes preconfigured with a video editing screen setup. Video files are in cyan, sound in blue, and image sequences are in purple, so you can tell at a glance what you're working with.

The VSE is, to say the least, pretty strange. Like all things in Blender, the interface is built for efficiency and speed of use over user-friendliness, so the learning curve is a bit steep, although knowing a good bit about how the rest of Blender works will help out handsomely.

Blender's major shortcomings to this point, as a video editor, have been threefold:

As it started life as an animation editor, it hasn't had support for fractional framerates such as are found in NTSC (29.97), which causes sound sync problems when editing NTSC footage with sound. This is now fixed in CVS, and with any luck, it will be in the next main release before this article goes to press.

Its export paradigm is obtuse and hard to cope with, setting an entry bar too high for most editors to be willing to consider. A bit of practice makes this a non-issue.

It also has no asset management system—all that work has to be done outside the program by editors carefully structuring their directories and assets if they care to keep track of everything. This probably never will be addressed—thus far, there isn't a significant cry from within the user community to change it, and I suspect it would take some nontrivial code refactoring to pull it off.

However, despite these initial weirdnesses, Blender's VSE has a lot to recommend it, not the least of which is its easy integration with the other parts of Blender. It can accept as inputs both rendered and unrendered strips from the animation subsystem and the compositing subsystem—a very powerful bonus. The compositing system itself (reviewed in the November 2007 issue of LJ) is a full-fledged professional nodes-based system that goes far beyond the video effects available in any other Linux editor. Additionally, Blender's VSE is itself a layers-based compositor, with quite a few native and community-generated plugins for color correction, greenscreen compositing, PIP work and so on.

In practice, this means that, when properly used, Blender's VSE has, by one path or another, all the power of After Effects (sans easily usable rotosplines), particularly for plane-based animation, a trick I use regularly to design animated DVD menus. It also has a professional color-correction tool that is totally absent from the other editors in this article, a vectorscope.

For format compatibility, Blender shares the FFmpeg backbone with KDENLIVE and OpenMovieEditor (initially integrated into Blender by Ian Gowen as a Google SoC project), and it deals excellently with image sequences (which is only natural, as it was originally an animation editor). Its audio compatibility also is FFmpeg-based, and although Blender's audio tools are paltry to the point of vanishing, it is quite suitable for video editing where a separately mixed soundtrack is conformed to the video in the VSE.

Like OpenMovieEditor and unlike KDENLIVE, Blender's VSE is format-agnostic—the final output profile being controlled by the output settings in the RenderButtons window.

Alas, Blender VSE has one more shortcoming: unlike KDENLIVE or OpenMovieEditor, it has no option for direct stream copy to prevent generation loss when rendering out to the same format you are using for your source footage. If you're using Blender as a finishing system, this isn't an issue; most of your footage will have effects applied and thus be recompressed on export anyway.

I personally don't use Blender as my primary video editor, though I have found myself using it more and more as a finishing system and may give it a go doing a full project on it sometime in the not-too-distant future. It's an odd mix of best-of-bunch and worst-of-bunch, which might not seem like a glowing recommendation, but it is an indispensable tool for a Linux production pipeline.

Of course, there are a number of projects I haven't mentioned here. Without exception, they are all unusable. They either haven't achieved usability yet (Pitivi and Jahshaka), they are poorly designed, unstable and resource-hungry (Cinelerra), or they are dead on the vine (MainActor and Diva).

One of the great weaknesses in open-source software in the video domain thus far has been a lack of imagination. In the commercial world, because of the way the industry has developed, there long have been a handful of sharply divided paradigms for editing. Market strategy being what it is, it's in the interest of commercial developers to keep their products for the various paradigms in separate tracks: more programs equals more redundant software sales, and the ability to set high prices for some markets while giving away the software for other markets (usually bundled with hardware). So far, open-source developers have been content to emulate it, and it's a philosophy that has hobbled the development of a killer app for video editing on Linux. All three of the projects covered here would do well to take a look at the asset management, footage commenting and multicamera switching strategies innovated by Drew Pertulla and implemented in his now-fallow multitrack editor Cuisine and at other innovations among the also-rans.

Fortunately, OpenMovieEditor and Blender are starting to break the mold, and I have high hopes that KDENLIVE will follow suit.

However, what's left is quite usable and in some cases bordering on downright impressive. So, grab your cameras, get a script, and dive on in!