This edition of diff -u is dedicated to David Brownell, a kernel hacker who gave a lot his time and creativity to Linux, and a lot of help and encouragement to many open-source developers. Rest in peace, David. May your name linger long in the source tree.

Pekka Enberg has been working on a helpful virtualization tool to make it relatively straightforward to boot a virtual system on a running Linux box. There are various virtualization tools available, but Pekka says this one is intended to be a clean, lightweight alternative that anyone could use.

Tony Ibbs has released KBUS, available at kbus-messaging.org. It's a message-passing framework, intended to support software running on embedded systems. The main idea is that it will be very reliable: a process that dies before it can send a needed message still will have a message sent by KBUS on its behalf; messages flying through the system will all arrive in a predictable order, making their significance easier to interpret; and messages that are sent by one process are as nearly as possible guaranteed to arrive at their destination.

Dan Rosenberg kicked off a new drive to increase Linux security, when he posted some patches to hide the /proc/slabinfo file from regular users. It turned out that his approach was too much of a blunt instrument, with too little gain, for certain folks' taste. But in the process of debating its various merits, a bunch of folks, including Linus Torvalds, dove into the memory allocation code, trying to figure out ways of preventing various security exploits that had been seen in the recent past.

David Johnston alerted the kernel folks to the idea that some of his code had been included in the kernel, without attributing him as the author and without having been licensed by him to be included in the source tree. It appeared to be a clear copyright violation. David actually said he'd be pleased and honored to have his code in the kernel; he just wanted to make sure the attribution was correct, and the license issues sorted out. So a few folks worked on finding out how the code had gotten into the kernel in the first place and how to fix the attribution. These kinds of debates always are fascinating, because they put everyone in the awkward position of already having done something wrong and trying to figure out the best legal and ethical way to back out of it again.

A bit of political wrangling: David Brown tried to remove Daniel Walker and Bryan Huntsman from the MAINTAINERS file, as the official maintainers of ARM/Qualcomm MSM machine support. Bryan was fine with this, but Daniel had not given his approval. It turned out that Bryan and David were both industry folks, and Daniel wanted to remain a maintainer, partly in order to make sure they “did right by the community”. As Linus Torvalds pointed out during the discussion, there was no real reason for any good maintainers to be supplanted if they didn't want to step down. Their contribution could be only positive, and so the argument by the industry folks amounted to an exclusivity that Linus said he found distasteful. And as Pavel Machek pointed out, the fact that David had thought it would be okay to do this in the first place was a good enough argument that he wasn't yet ready to be a sole maintainer.

If you are an Ubuntu user and a fan of the new Unity interface, you might be interested in a new lens in development by David Callé. The Books Lens provides a real-time search interface for e-books. It currently interfaces with Google Books, Project Gutenberg and Forgotten Books. By the time you read this, that list probably will have grown.

The Books Lens instantly finds metadata on your search, including book covers, and gives you direct links to the books themselves. For us book nerds, it's quite a handy little tool. Check it out yourself at https://launchpad.net/unity-books-lens, or install the PPA with:

sudo apt-add-repository ppa:davicd3/books-lens

Then, install the package unity-books-lens.

One of the things that frustrates me about GNOME is the lack of wallpaper rotation integration. Thankfully, several tools are available to remedy that shortcoming. My current favorite solution is DesktopNova by Stefan Haller. DesktopNova not only lets you add multiple folders to your wallpaper rotation group, it also optionally allows you to show a tray icon to interact with it.

DesktopNova comes precompiled for several distributions, and it already may be in your repository. When combined with the hundreds of space photos I've downloaded from NASA, DesktopNova makes my computing experience out of this world! (Yes, I think that counts as the cheesiest thing I've written all year.)

Check it out at sites.google.com/site/haliner/desktopnova.

DesktopNova has many options to set, and a convenient method to set them.

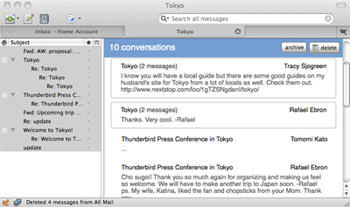

Most people are familiar with Thunderbird. In fact, I used its predecessor back when it was just a part of the Netscape Communicator suite. Thunderbird has come a long way in recent months, however, and it's still being developed very actively. If you haven't checked out some of its new features, now might be the time to do so. Thunderbird supports Gmail-style archiving, tabs and better searching, and it's completely extensible with add-ons.

Oh, and if you're stuck with Windows or OS X, no problem! Thunderbird always has been a cross-platform e-mail solution, and it still is. It makes the transition from one platform to another easier for users, and if you don't like your e-mail to be kept on some Web company's servers, it might be the ideal e-mail solution for you. Check it out at getthunderbird.com.

One area that chews up a lot of cycles on machines around the world is CFD. What is CFD? CFD is short for Computational Fluid Dynamics. The general idea is to model the flow of gases and liquids (or fluids) as they interact with solid surfaces. This type of modeling is used in designing aircraft, automobiles, submarines and fan blades—basically, anything that travels through water or air. As you increase the complexity of the surfaces, or increase the complexity of the flow (such as going from subsonic to supersonic), the amount of computer time needed to model it goes up. One of the big packages available to do CFD is the suite of programs made by Ansys. Several groups here at my university use it. But, there is an open-source option available, OpenFOAM (www.openfoam.com). This month, I describe what you can accomplish with OpenFOAM. The OpenFOAM Project includes binary packages as deb files or RPM files. You also can download a source code package of files or even download directly from the Git repository.

OpenFOAM (Open Source Field Operation and Manipulation) basically is a set of C++ libraries that are used in the various processing steps. OpenFOAM, just like most other CFD packages, breaks down the work to be done into three separate steps. The first step is called pre-processing. In pre-processing, you define the problem you are trying to model. This involves defining the boundary conditions given by the solid objects in your model. You also describe the characteristics of the fluid you are trying to model, including viscosity, density and any other properties that are important for your model. The next step is called the solver step. This is where you actually solve the equations that describe your model. The third step is called post-processing. This is where you take a look at the results and visualize them so that you can see what happens in your model. An obvious consequence of this breakdown is that most of the computational work takes place during the solver phase. The pre- and post-processing steps usually can be done on a desktop, while the solver step easily can use up 50 or 100 processors. OpenFOAM includes several pre- and post-processing utilities, along with several solvers. But the real power comes from the fact that, because OpenFOAM is library-based, you can build your own utilities or solvers by using OpenFOAM as a base. This is very useful in a research environment where you may be trying something no one else ever has.

A model in OpenFOAM is called a case. Cases are stored as a set of files within a case directory. Many other CFD packages use a single file instead. A directory allows you to separate the data from the control parameters from the properties. Case files can be edited using any text editor, such as emacs or vi. Pre-processing involves creating all of the files required for the case you are investigating.

The first step is mesh generation. Your fluid (be it a liquid or a gas) is broken down into a collection of discrete cells, called a mesh. OpenFOAM includes a number of utilities that will generate a mesh based on a description of the geometry of your fluid. For example, the blockMesh utility generates simple meshes of blocks, and the snappyHexMesh utility generates complex meshes of hexahedral or split-hexahedral cells. If you want to generate a basic block mesh, you would lay out the details in a dictionary file, called blockMeshDict, in the subdirectory constant/polyMesh within your case subdirectory. The file starts with:

FoamFile

{

version 2.0;

format ascii;

class dictionary;

object blockMeshDict;

}

Case files, in general, start with a header of this format, describing what each case file consists of. In this particular file, you can define sections containing vertices, blocks, edges or patches. Once you have created this file, you can run the blockMesh utility to process this dictionary file and generate the actual mesh data that will be used in the computation.

The next step is to set your initial conditions. This is done by creating a subdirectory called 0 and placing the relevant case files here. These case files would contain the initial values and boundary conditions for the fields of interest. For example, if you were looking at a fluid flowing through a cavity, you may be interested in the pressure and velocity. So, you would have two files in the 0 subdirectory describing these two fields. You also need to set any important physical properties in files stored in the Dictionaries subdirectory. These files end with Properties. This is where you would define items like viscosity. The last step in pre-processing is to set up the control file. This file is named controlDict and is located in the system subdirectory. As an example, let's say you wanted to start at t=0, run for 10 seconds with a timestep of 0.1 seconds. This section of the control file would look like this:

startFrom startTime; startTime 0; stopAt stopTime; stopTime 10; deltaT 0.1;

You also set output parameters in this control file. You can set how often OpenFOAM writes output with the writeControl keyword. So, let's say you want to write out the results every 10 timesteps. That section of the control file would look like this:

writeControl timeStep; writeInterval 10

This tells OpenFOAM to write out results every 10 timesteps into separate subdirectories for each write. These subdirectories would be labeled with the timestep.

You also can set the file format, the precision of results and file compression, among many other options.

Before you actually start the solver step, it probably is a good idea to check the mesh to be sure that it looks right. There is a post-processing tool called paraFoam that you can use. If you are in your case directory, calling paraFoam will load it up. Or, you can specify another directory location with the command-line argument -case xxx, where xxx is the case directory you are interested in.

The next step is to run a solver on your model and see what you get. Solvers tend to be specialized, in order to solve one particular class of problem efficiently. So OpenFOAM comes with a rather large set of standard solvers out of the box. If you are interested in solving a laminar flow problem for an incompressible fluid, you likely would use icoFoam. Or, if you are interested in looking at cavitation, you could use cavitatingFoam. Or, you may want a solver for internal combustion engines (engineFoam). Take a look at the documentation to see what is available. Once you know which solver you are going to use, you can run it by simply executing the relevant binary from within your case directory, or you can use the -case command-line argument to point to another case directory.

The last step is the post-processing step, where you actually look at the results and see what happened inside your model. Here, you can use the supplied utility paraFoam. It can accept a -case command-line argument, just like all of the other utilities I've discussed. You then can manipulate the data and look at various time slices. You can generate isosurface and contour plots, vector plots or streamline plots. You even can create animations, although not directly. You can make paraFoam output image files representing movie frames. So they would be saved with filenames of the form:

fileroot_imagenum.fileext

Then, you can take this sequence of images and run them through something like the convert utility from ImageMagick to bundle them together into a single movie file.

As a final comment, in both the pre- and post-processing steps, there are utilities that allow you to convert to and from file formats used by other CFD packages, including fluent, CFX and gambit, just to name a few. This comes in handy if you are collaborating with other people who happen to be using one of these other packages. If you are working with someone who is using fluent, you would use fluentMeshToFoam in your pre-processing step and foamMeshToFluent in your post-processing step.

This short article provides only a small taste of OpenFOAM. If you are interested in fluid dynamics, you definitely should take a look at OpenFOAM. The home page includes links to great documentation and several tutorials. The installation package also includes several example cases, so you can see how standard problem sets are handled. You usually can use one of these examples as a jumping-off point for your own problem. Check it out and see if it can help you in your work.

Vote for your Linux and open-source favorites in this year's Readers' Choice Awards at www.linuxjournal.com/rc11. Polls will be open August 2–22, 2011, and we'll announce the winners in the December 2011 issue of Linux Journal.

If at first you don't succeed, call it version 1.0.

—Unknown

WE APOLOGIZE FOR THE INCONVENIENCE—God

—Douglas Adams, So Long and Thanks for All the Fish

All Your Base Are Belong To Us

—Zero Wing (Nintendo Game)

Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.

—J. Robert Oppenheimer

Klaatu barada nikto.

From 1951's The Day the Earth Stood Still

This month's issue is all about community. The Linux and Open Source community is what keeps all of us motivated and having fun with what we do. These communities range in size and scope from a small LUG in your hometown, to the distributed development teams on the largest Linux distributions, to other Open Source communities that exist to support projects like Drupal. They are all part of the larger ecosystem that is open-source software. We also like to think of LinuxJournal.com as its own community, and we hope you'll join us.

Visit www.linuxjournal.com/participate to connect with Linux Journal staff and others, check out our forums and learn about community events. We encourage you to chime in with your comments, and let your opinions be known. It's a great way to give and get feedback from our writers and readers. We also invite you to visit us on Freenode on our IRC channel, #linuxjournal. There, you'll find Linux Journal staff and readers who always are eager to share stories and sometimes lend a hand. See you there!

Xbox Media Center (XBMC) is one of those projects whose name makes less and less sense as time goes on. Sure, people still are using XBMC on an actual Microsoft Xbox, but for the most part, XBMC now is run on computers. In fact, recent versions of XBMC installed on an ION-based nettop makes just about the perfect media center. Version 10 (Dharma) introduced a fancy plugin system that allows XBMC to be extended beyond its built-in media-playing abilities. The next version, currently in development, will focus partially on recording as well as playback.

When it comes to performance, it's hard to beat XBMC. It's faster and more responsive than a Boxee Box, has local media playback unlike the Roku, and is open source, unlike Microsoft's media center options. It does currently lack in premium on-line streaming, but that's largely because the live version is based on Linux. It's a trade-off I'm willing to make. (I actually keep a Roku for that purpose and use XBMC for everything else.)

Check out the latest features and download a copy for your operating system at xbmc.org.