Some futex benchmarking code seems to be making its way into the official Linux tree. Hitoshi Mitake started porting over some of Darren Hart's and Michel Lespinasse's out-of-kernel benchmarking suite and turning it into a new perf subsystem for futexes.

Futexes are simple locking mechanisms that allow the kernel to divvy up resources among all the users on a given system, without each user's actions conflicting with any of the others. There are a lot of simple and complicated locking mechanisms in the kernel, and futexes are used in the design of many of them. Without them, the kernel would have a tough time being multitasking.

Darren had no major objections to Hitoshi's work, and Hitoshi suggested migrating even more of Darren's futex test code into perf's tools/ directory, because it offered good examples of how to use futexes, in addition to being useful test code in general. Everyone seemed favorable, so it looks like this will happen.

It can be difficult to navigate the vicissitudes of feature requirements. Sometimes a seemingly inexplicable aspect of a feature can turn out to be needed by one particular corner case of users.

John Stultz recently tried to improve the way the kernel handled anonymous memory on swapless systems. He'd noticed that anonymous RAM was tracked on two lists: an active page list and an inactive page list. Inactive pages typically would be swapped to disk if they went unused too long. But on swapless systems, inactive pages would just sit on the inactive list, making that list seem irrelevant. John proposed that on swapless systems, it made more sense to have just a single list.

Minchan Kim pointed out that he too had tried introducing a similar refinement, but that Rik van Riel had vetoed his patch. The reason Rik gave was that swapless systems were not always entirely swapless—sometimes they were systems where swap had been only temporarily disabled, or systems where there really was not going to be any swap, but people still could enable it if they wished. In that case, the absence of an inactive page list would make it harder to use the newly available swap space.

Back in June, the world gained a “leap second”, and Richard Cochran wrote up some code in preparation for it that he hoped would be less messy than the current way such things were handled in the kernel. The problem, apparently, is that POSIX UTC was designed as a standard back in the before-time, when computer clocks were highly inaccurate, and no one could clearly anticipate why any such issues would matter in the future.

But, to be POSIX-compliant, Linux still has to support POSIX UTC. Richard's answer to this was interesting. Instead of actually implementing POSIX UTC as the true “Way of the Kernel”, he implemented a better system that could track things like leap seconds and other oddities. And then, for the benefit of any user threads that wanted POSIX semantics, Richard's code would translate the inner timekeeping mechanism into UTC for that process.

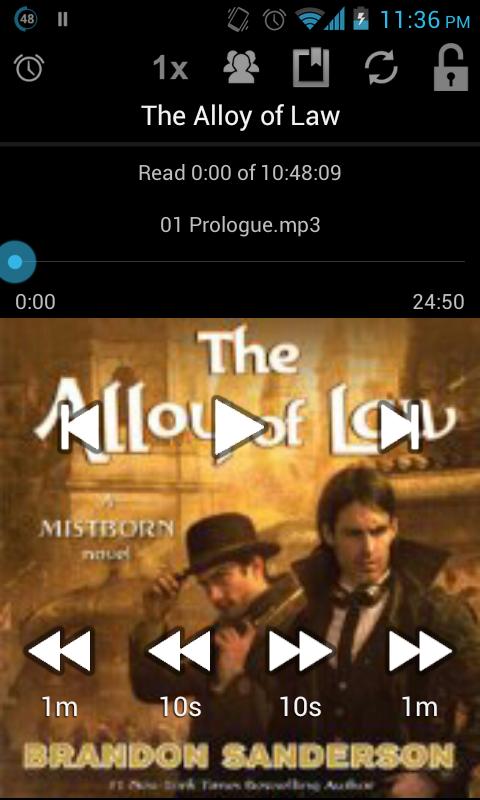

The Audible app for Android is a great way to consume audiobooks. You have access to all the books you've purchased on Audible, and you can download them at will. Plus, the app provides all the bookmarking features you'd expect from a professional application. Unfortunately, if your audiobooks are from somewhere other than Audible, you need something a little more flexible.

For non-DRM audiobooks, there are a few stand-out apps. Mort Player and Audiobook Player 2 are the standbys I've been using for a couple years, but the newer Smart Audiobook Player is truly an amazing piece of software. Although it boasts the same features you'd expect from any audiobook player, Smart Audiobook Player also includes:

Support for almost every audio format, including .m4b (the format iPods use).

Built-in cover art searching and downloading.

Lock screen feature to avoid accidental chapter skipping.

Playback speed adjustment.

Audiobooks are organized by putting each book, whether it is a single large file or many small files, into its own folder. Smart Audiobook Player treats each folder as a separate book and sorts the files inside each folder by filename. In order to keep audiobook files from appearing in your music collection, a simple .nomedia file can be added to your root audiobook folder.

Although the features all work together to make an incredible audiobook player, by far my favorite feature is the speed control. By setting playback speed to 1.2x, the voices are still quite comprehensible, and you can cram more book into each morning commute. Smart Audiobook Player is free, but for a $2 in-app purchase, you can unlock the “Full” features permanently, allowing for bookmarking of several books simultaneously, and a few other nifty features. If you listen to audiobooks, but don't purchase them all directly from Audible, you owe it to yourself to try Smart Audiobook Player: is.gd/smartaudiobook.

Every time my paycheck is direct-deposited, I contemplate purchasing a Chromebook. Long gone are the days of the CR-48 laptops with the clunky interface and frustrating usability. Although I never quite seem to pull the trigger and buy a Chromebook, thanks to the developer Hexxeh, it's possible to run the Chromium OS on a wide variety of hardware combinations. I'm writing this on my Dell Latitude D420 booted into Hexxeh's Vanilla build of Chromium. (I'm using the excellent Chrome App Writebox as an editor.) You can get the most recent build of Vanilla from Hexxeh's Web site: chromeos.hexxeh.net.

Image from hexxeh.net

The exciting news, however, has nothing to do with laptops at all. Like most Linux-based pseudo-embedded projects, Hexxeh's Chromium build is getting ported to the Raspberry Pi. Once complete, a Chromium-enabled Raspberry Pi desktop machine will be a very affordable, power-sipping alternative to Google's ChromeBox units. Projects like this really beg the question: is there anything the Raspberry Pi can't do? For more details on the Pi port, visit Hexxeh's blog: hexxeh.net.

If you're using Windows and want an incredible virtual music studio, DarkWave Studio is something you definitely should check out. Licensed under the GPLv3, DarkWave Studio has a slew of built-in audio plugins, and it supports VST and VSTi plugins out of the box.

Screenshot Courtesy of www.experimentalscene.com

The DarkWave Studio installer includes both the 32-bit and 64-bit versions of the program. Once installed, you can create electronic music, mix existing sounds and do post-production editing as well. A shining example of open-source programming, DarkWave Studio has a modular design allowing for third-party instruments and plugins while keeping its source code completely open. Check out DarkWave Studio at www.experimentalscene.com.

In quantum physics, one of the calculations you might want to do is figure out how two or more particles may interact. This can become rather complicated and confusing once you get to more than two particles interacting, however. Also, depending on the interaction, there may be the creation and annihilation of virtual particles as part of the interaction. How can you keep all of this straight and figure out what could be happening? Enter the Feynman diagram (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Feynman_diagram). American physicist Richard Feynman developed Feynman diagrams in 1948. They represent complex quantum particle interactions through a set of very simple diagrams, made up of straight lines, wavy lines and curly lines. This works really well if you happen to be using a chalk board or white board. But, these media are not very useful when sharing your ideas across the Internet. Additionally, most word-processing software is unable to draw these diagrams for your articles, papers and documents. So what can you do? Use the JaxoDraw software package (jaxodraw.sourceforge.net).

JaxoDraw provides a graphical environment for drawing Feynman diagrams on your computer. JaxoDraw is a Java application, so it should run on any OS that has a reasonably recent Java virtual machine. There currently are packages only for Fedora and Gentoo, but both source and binary downloads are available. The binary download is a jar file containing everything you need. There also are installers for Windows and a disk image for Mac OS X users. You also can download the source files and compile JaxoDraw for yourself or make alterations to the sources to add extra functionality. JaxoDraw supports a plugin architecture, with documentation on how to create your own. This might be a more effective way of adding any extra functionality you need.

Let's use the most flexible setup for JaxoDraw. This involves downloading a tarball from the main Web site, in the Downloads section. The filename you should see is jaxodraw-x.x-x-bin.tar.gz. Once this file is downloaded, you can unpack it with the command:

tar xvzf jaxodraw-x.x-x-bin.tar.gz

This will create a subdirectory containing the jar file and some documentation files. To start up JaxoDraw, first change to the new subdirectory and run:

java -jar jaxodraw-x.x-x.jar

Be aware that currently the GNU Java virtual machine doesn't run JaxoDraw. On start up, you will have an empty canvas and a list of the elements available to draw your Feynman diagram (Figure 1). The left-hand side is broken into several sections, including the types of particles or the types of edits available. JaxoDraw uses XML files to save Feynman diagrams. This way, you can load them again later to make edits or build up more-complicated reactions.

To begin drawing, first select an object type from the left-hand side. The regular particle types are fermions (straight lines), scalars (dashed lines), ghost (dotted lines), photons (wiggly lines) and gluons (pig-tailed lines). In the diagrams, there are four versions of these particle lines: lines, arcs, loops and beziers. Once you select one of those, you can draw on the canvas by clicking and dragging to draw the relevant line. You can draw anywhere on the canvas, or you can force the drawing to snap to grid points. The spacing of these grid points is adjustable in the Preferences. At least in the beginning, you probably will want to turn this on so that you can make the different sections of your drawing line up. Each of the elements of your drawing has properties that can be edited. You need to select the edit tool from the left-hand side, and then select the element you want to edit (Figure 2).

From here, you can edit the location, whether there is an arrow and which direction it points, the line width and arrow dimensions. There is also a text element you can use to label your diagram. You can enter text in either LaTeX format or PostScript format. This allows you to use special characters, such Greek letters, in your text label. One thing to remember is that you can't mix PostScript and LaTeX text objects. Be sure to select the text type based on what you want to produce for exported output.

You can group a number of diagram elements together in a single entity. You need to press the selection tool on the left-hand side and then click on each of the entities for the group you are creating. This grouped entity then can be moved as a single object. You can group together these groups into super groups. There is no technical limit to this type of nesting.

You can get a rough idea of what your Feynman diagram will look like, but things like LaTeX text aren't rendered on the drawing canvas. You need to pass it through a rendering program and then view the output. You will need to go to Options→Preferences and set the paths for the helper programs. To get a preview of your finished diagram, be sure to set the preferred PostScript viewer, the LaTeX path and the dvips path. A common PostScript viewer is gv, the viewer that comes with ghostscript.

Once you have finished your diagram, save it as a JaxoDraw XML file. This way, you always can go back and re-create the diagram if needed.

You can export your Feynman diagram in one of several formats. You can export into image files (JPEG and PNG). This is useful if you are using PowerPoint or Web pages or some other software package that doesn't understand LaTeX or PostScript. You also have the option to export into LaTeX or PostScript file formats. If you export to LaTeX, you need to include the JaxoDraw LaTeX style file to handle the rendering of your Feynman diagram. This style file is called axodraw4j.sty, which is based on J. Vermaseren's original axodraw.sty (www.nikhef.nl/~form/maindir/others/axodraw/axodraw.html). This is now a separate download from the main JaxoDraw application download. You will want to install this where your LaTeX installation can find it and use it. The easiest thing to do is copy it into the same directory as your LaTeX document source files. LaTeX searches there by default when you render your LaTeX documents. axodraw4j.sty is still in beta, so you may want to stick with the original axodraw package. This package also is needed if you want to preview your diagram in JaxoDraw.

Now that I've covered some of JaxoDraw's features, let's look at drawing one of the classic particle interactions. This is where an electron and a positron collide, producing photons. The first step is to draw two fermions, with arrows pointing in opposite directions (Figure 3). In these diagrams, space is in the vertical direction, and time is in the horizontal direction. Time increases from left to right. The electron and positron collide and annihilate, producing at least one photon (Figure 4).

At the time of this writing, four plugins are available. These are different export functions. Two of them are for exporting to PDF or SVG file formats. The third one is to serialize your diagram in the Java binary file serialization format. This format should be functionally equivalent to the XML file format, but it is smaller and loads faster, especially for larger diagrams. The only problem with it is that it is a binary file format, so you can't take a look inside it. The last plugin is just a text exporter. It provides a template to show you what a simple custom exporter looks like.

JaxoDraw has a plugin manager to handle installing and uninstalling plugins (Figure 5). You simply have to download the relevant jar file, then use the plugin manager to install it. Plugins are stored at $HOME/.jaxodraw/$VERSION/plugins. If you like, you can install plugins manually by dropping the associated jar file into this directory. To uninstall manually, you can delete the relevant jar file and any corresponding property files from this location.

With the possible sighting of the Higgs boson at the LHC, interest in particle physics is growing. Now, with JaxoDraw, you too can write about particle interactions and be able to draw a proper picture to show others what you are trying to describe. Have fun, and share your insights with others.

We recently asked our LinuxJournal.com readers to answer a poll about all things Linux kernel, and we present the answers below. Although it's clear that we have readers with widely varying experiences, a few answers stand out. We're happy to learn that most of you have read the GNU GPL v.2, and that a full 40% of you have helped a friend compile the kernel for the first time. We're not at all surprised to learn that 68% of you have read the kernel source code just for fun, and that 27% have grepped for naughty words. We do, however, wonder how the 17% of you who have never sacrificed sleep to keep coding have managed it. We'll just assume programming isn't your thing in order to feel better about our own time management skills. And finally, I would love to know more details on the machine that has had 3,649 days of uptime.

1. What's the earliest kernel version you've used?

0.01: 1%

0.02–0.12: 2%

0.95–1.0.0: 12%

1.2.0–2.2.0: 39%

2.4.0–2.6.x: 39%

3.0–3.5.1: 7%

2. Have you ever read the GNU General Public License, version 2?

Yes: 63%

No: 37%

3. Have you ever configured and compiled the kernel yourself, from source code?

Yes: 80%

No: 20%

4. Have you ever helped a friend compile the kernel for the very first time?

Yes: 40%

No: 60%

5. Have you ever compiled a kernel on one architecture, that was intended to run on a different architecture?

Yes: 30%

No: 70%

6. Have you ever compiled a kernel on a virtual Linux machine running on your own hardware?

Yes: 35%

No: 65%

7. Have you ever compiled other free software kernels (BSD, GNU Hurd and so on)?

Yes: 25%

No: 75%

8. Have you ever run an alternative free software OS (BSD, GNU Hurd and so on) under a virtual machine on a Linux box?

Yes: 52%

No: 48%

9. Have you ever tried to find out how deeply you could nest virtual machines under Linux before something would break?

Yes: 12%

No: 88%

10. Have you ever browsed through the /proc directory and catted the files?

Yes: 85%

No: 15%

11. How many days are given as the output if you run uptime on your current computer right now?

Less than 7: 53%

8–30: 19%

31–180: 16%

181–365: 7%

366–730: 4%

More than 730 (and if so, how many): 1% (longest uptime was 3,649 days)

12. Have you ever boasted about your Linux uptime (not counting this poll)?

Yes: 45%

No: 55%

13. Have you ever reported a kernel bug to the linux-kernel mailing list?

Yes: 15%

No: 85%

14. Have you ever upgraded your kernel because of a bug you'd heard existed in your running version?

Yes: 63%

No: 37%

15. Have you ever read some of the kernel source code for fun?

Yes: 68%

No: 32%

16. Have you ever grepped for naughty words in the kernel source tree?

Yes: 27%

No: 73%

17. Have you ever run git log (or the equivalent) on a kernel tree and read the patch comments for fun?

Yes: 24%

No: 76%

18. Have you ever edited the kernel source code, and compiled and used the result?

Yes: 39%

No: 61%

19. Have you ever submitted a kernel patch to the linux-kernel mailing list?

Yes: 7%

No: 93%

20. Have you ever maintained your own kernel patch across multiple official releases of the kernel?

Yes: 8%

No: 92%

21. Have you ever run a program as a regular user just because you heard it could crash a Linux box?

Yes: 38%

No: 62%

22. Have you ever written a program whose purpose was to expose bugs in (or crash) the kernel?

Yes: 18%

No: 82%

23. Without looking it up, do you know what the SCO lawsuit was about?

Yes: 65%

No: 35%

24. Without looking it up, do you know how Linus Torvalds came to own the Linux trademark?

Yes: 45%

No: 55%

25. Without looking it up, do you know what events precipitated Linus' migration away from BitKeeper, and his creation of git?

Yes: 50%

No: 50%

26. Without looking it up, do you know why Microsoft was legally forced to contribute code to the Linux kernel?

Yes: 34%

No: 66%

27. Have you ever read any POSIX specifications?

Yes: 50%

No: 50%

28. Have you ever had an argument with someone else about whether a given Linux kernel feature was POSIX-compliant or not?

Yes: 13%

No: 87%

29. Have you ever tried to write a standard or a specification for anything?

Yes: 38%

No: 62%

30. Have you ever sacrificed sleep in order to keep coding?

Yes: 83%

No: 17%

It's getting harder and harder to differentiate between schizophrenics and people talking on a cell phone. It still brings me up short to walk by somebody who appears to be talking to themselves.

—Bob Newhart

The only still center of my life is Macbeth. To go back to doing this bloody, crazed, insane mass-murderer is a huge relief after trying to get my cell phone replaced.

—Patrick Stewart

The single biggest problem in communication is the illusion that it has taken place.

—George Bernard Shaw

Effective communication is 20% what you know and 80% how you feel about what you know.

—Jim Rohn

Of all of our inventions for mass communication, pictures still speak the most universally understood language.

—Walt Disney

This month, all subscribers will receive a bonus issue in addition to their regular October 2012 issue of Linux Journal. This Drupal Special Edition focuses on Drupal's versatility as a CMS, a platform and as a base on which to develop products and distributions. This special issue features articles with technical takeaways for all levels of Drupal users and developers. So, whether you're a seasoned developer or just curious about Drupal and its capabilities, I encourage you to dive in.

In this special issue, you'll learn more about Drupal's hook system, the Drupal community, how to create a re-usable installation profile, how a distribution aimed at higher education scrapes and imports large amounts of data, continuous integration options, customizing the popular Open Atrium distribution, and much more.

Subscribers will receive a notification when the Drupal Special Edition is ready for download, or you can find out how to get a copy at www.linuxjournal.com/special/drupal2012.

I've reviewed plenty of simple text editors designed for writers. For my writing, I really desire only a few features:

Support for plain text.

Spell Czech.

Running word count.

Oddly enough, the last item is the most difficult to find. In fact, most text editors don't have a running word count, even though that's the metric most writing is measured by. In fact, the editor I'm using right now, from is.gd/writebox, didn't have that simple feature when I first started using it. I e-mailed the developer, and within hours, the feature was added to the application!

If you followed the link, you'll notice Writebox is a Chrome application that runs completely inside your browser. Because it's a Web application, when the running word-count feature was added, it instantly was available to all users. If a text-only editor with Dropbox syncing, off-line support and a running word count sounds like the text editor of your dreams, check out Writebox.