The stable kernel series recently got bit by an over-eagerness to accept patches. Typically, the rule had been that Greg Kroah-Hartman wouldn't accept patches that had not gotten into Linus Torvalds' development kernel first. People sometimes complained that this was absurd, since the patches in question always were intended for the stable tree, and so it seemed to make no sense to wait for them to be accepted into a completely different, development-centric tree. But the rule existed to ensure that the good and useful stabilization patches wouldn't go only into the ephemeral stable releases, but also would be incorporated into the long-term future of the kernel (that is, Linus' tree).

Nevertheless, sometimes people complained. And, Greg did try to take patches as soon as they crossed the threshold into Linus' git repository. But recently he did this with a genetlink patch that seemed fine at first, but it ended up having a bad interaction with other code that wasn't caught until after the 3.0.92 stable kernel came out.

Greg viewed this as a bit of a wake-up call to slow down on accepting patches until they were not only in Linus's tree, but also had a chance to be tested for the duration of one -rc cycle. That would provide a much better chance of shaking out any bugs and keep the stable kernels as stable as one might reasonably expect.

Linus pointed out that tying the waiting period to an -rc cycle was fairly arbitrary. He said waiting a week or so probably would be fine. He also added that for particularly critical or well-discussed patches, a delay probably would be unnecessary.

Greg posted a more formal description of his new patch-acceptance policy, which also specified that if an official maintainer signed off on the patch, or if Greg saw a sufficient amount of discussion about it, or for that matter, if the patch was just obvious, then the delay for acceptance could be skipped.

Greg's initial proposal also included his idea of waiting for a full -rc cycle. Nicholas A. Bellinger had no problem with that, and Willy Tarreau said that even waiting for a full dot release would be fine. But Greg vetoed that, saying three months would be too long.

Josh Boyer offered to help out in some way, and Greg said it would be useful to know when things were broken. He said, “Right now, that doesn't seem to happen much, so either not much is breaking, or I'm just not told about it, I don't know which.” So Josh volunteered to send any such information he collected as part of his work on Fedora to Greg. Greg said this would be great. Greg also suggested that patches going into distribution kernels also should be sent to him as a matter of course, “as those obviously are things that are needed for a valid reason that everyone should be able to benefit from.”

At some point in the discussion, Linus came back and again recommended that Greg just wait a week to accept patches, rather than wait for an -rc release. Linus pointed out that some people did test the bleeding-edge git kernels, and there at least should be some encouragement for them to keep doing so.

This led to a discussion of whether people actually should run the git kernels in between -rc releases. Borislav Petkov suggested that at any point in time the raw git tree would be fairly arbitrary and possibly broken. But, Tony Luck said that if the git tree never got any testing, all the arbitrariness and breakage simply would cascade forward into the -rc release.

It does seem as though Greg will be more careful about when patches go into the stable tree, and hopefully, some new people will start testing the raw git kernels.

The device tree (DT) bindings have begun a major overhaul. Grant Likely announced that maintainership would be changing to a group model to keep up with the pace of change in that area. He asked for volunteers to join in, and he said that the entire schema for specifying DT bindings will be revised.

DT bindings are generalized, machine-parsable descriptions of certain aspects of hardware. They make it possible for the kernel code to be somewhat more generic and avoid the need to hard-code a lot of hardware-specific details. It makes for a much cleaner and more readable kernel.

Grant said that Tomasz Figa was going to be leading the work on revising the DT schema. This, he said, hopefully would result in something that could be validated programmatically, while at the same time being human-readable, in order to double as documentation.

The development process itself also will change. At the time of Grant's announcement, the process had become too frantic, and there was no distinction between DT bindings that were clearly stable and those that were in flux and still under development.

Tomasz suggested having a clear process for migrating any given DT binding from a staging area into a stable area. Once stable, he said, they should have the sanctity of an application binary interface (ABI), which typically must never be allowed to break backward compatibility.

David Gibson also was very interested in this project. He'd made an earlier attempt at schema validation, and he wanted to see if Tomasz could fare better. He also pointed out that there was a perception problem among users, and that they tended to think that a given DT binding—as being distributed in the kernel—was valid for that kernel and no others. But David said this was not the case, and that some effort should be made to inform users that DT bindings are intended to be generalized descriptions of hardware and not tied to any particular kernel version. But, he wasn't sure how that could be done.

The discussion took many paths. At some point, someone suggested using XML with a corresponding document type definition as the DT schema. There was some support for this, but Tomasz didn't like mixing XML with the existing DT schema format.

The overarching discussion was open-ended, but clearly there are big changes on the way, regarding the DT-binding specifications.

As luck would have it, shortly after I purchased a Flickr Pro subscription, Yahoo decided to eliminate the pay-for option with Flickr and give everyone a free Terabyte of space to store photos. Although I'm still not convinced Flickr is the best way to store photos, I have found it to be very flexible, so for now, my family members dump all their photos to Flickr from all their devices. (And then I back them up with https://pypi.python.org/pypi/flickrbackup because I'm paranoid.)

On my phone, a Galaxy S4, I find it cumbersome to upload photos directly to Flickr, so I bought Flickr Uploader from the Google Play store, and now all my photos are uploaded to Flickr instantly when I take them. Options are available to limit uploading to Wi-Fi only, or to upload only certain kinds of photos (camera photos but not screenshots, for example). The application is $4.99, but the developer has created “coupons” to get the application for a huge discount or even free (https://github.com/rafali/flickr-uploader/wiki/Coupons).

I find the application to be smooth, stable and incredibly convenient. It's important to realize, however, that if you're the sort of person to take personal or compromising photos, double- and triple-check your settings to make sure you don't upload publicly viewable shots automatically! If you're a Flickr user, check out Flickr Uploader today: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.rafali.flickruploader.

Hopefully by the time you're reading this, Chrome Desktop Applications will be available for Linux. In the meantime, this is a Windows treat. The ability to make a “single-purpose” browser has been around Chrome/Chromium for a long time, but with the new breed of Chrome Applications, the browser is a base for a standalone, off-line application. According to Google, the new Chrome apps will have the following features (from snar.co/chromeapps):

Work off-line: keep working or playing, even when you don't have an Internet connection.

More app, less Chrome: no tabs, buttons or text boxes.

Connect to the cloud: access and save the documents locally and in the cloud.

Desktop notifications: you can get reminders, updates and even take action, right from the notification center.

Local device support: interact with your USB, Bluetooth and other devices.

Automatic updates: apps update silently (unless permissions change).

Chrome App Launcher: appears on the taskbar when you install your first new Chrome App.

Chrome dabbles with off-line abilities with many of its current Web applications, but with the new Chrome Apps, this should go to an entire new level. If the hype is correct, these should be local applications, not just Web apps with off-line hooks. Also, although Chrome Apps are Windows-only today, Google promises Linux support in the future.

Many programs exist that try to serve as a replacement for MATLAB. They all differ in their capabilities—some extending beyond what is available in MATLAB, and others giving subsets of functions that focus on some problem area. In this article, let's look at another available option: FreeMat.

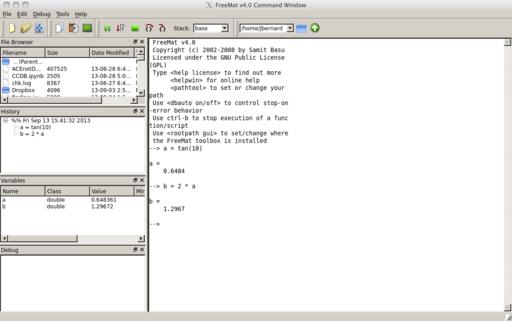

The main Web site for FreeMat is hosted on SourceForge. Installation for most Linux distributions should be as easy as using your friendly neighborhood package manager. FreeMat also is available as source code, as well as installation packages for Windows and Mac OS X. Once it's installed, you can go ahead and start it up. This brings up the main window with a working console that should be displaying the license information for FreeMat (Figure 1).

As with most programs like FreeMat, you can do arithmetic right away. All of the arithmetic operations are overloaded to do “the right thing” automatically, based on the data types of the operands. The core data types include integers (8, 16 and 32 bits, both signed and unsigned), floating-point numbers (32 and 64 bits) and complex numbers (64 and 128 bits). Along with those, there is a core data structure, implemented as an N-dimensional array. The default value for N is 6, but is arbitrary. Also, FreeMat supports heterogeneous arrays, where different elements are actually different data types.

Commands in FreeMat are line-based. This means that a command is finished and executed when you press the Enter key. As soon as you do, the command is run, and the output is displayed immediately within your console. You should notice that results that are not saved to a variable are saved automatically to a temporary variable named “ans”. You can use this temporary variable to access and reuse the results from previous commands. For example, if you want to find the volume of a cube of side length 3, you could so with:

--> 3 * 3 ans = 9 --> ans * 3 ans = 27

Of course, a much faster way would be to do something like this:

--> 3 * 3 * 3 ans = 27

Or, you could do this:

--> 3^3 ans = 27

If you don't want to clutter up your console with the output from intermediate calculations, you can tell FreeMat to hide that output by adding a semicolon to the end of the line. So, instead of this:

--> sin(10) ans = -0.5440

you would get this:

--> sin(10); -->

Assignment in FreeMat is done with the equals operator (=). Variable names are untyped, so you can reuse the same name for different data types in different parts of your worksheet. For example, you can store the value of tan(10) in the variable a, and the value of 2 times a in the variable b, with:

--> a = tan(10)

a =

0.6484

--> b = 2 * a

b =

1.2967

Notice that the variables active in your current session are all listed in the variable window on the left-hand side (Figure 2).

Figure 2. All of the current variables, along with their values and data types, are listed in the variable window.

The arithmetic operators are overloaded when it comes to interacting with arrays too. For example, let's say you want to take all of the elements of an array and double them. In a lower-level language, like C or Fortran, you would need to write a fair bit of code to handle looping through each element and multiplying it by 2. In FreeMat, this is as simple as:

--> a = [1,2,3,4] a = 1 2 3 4 --> a * 2 ans = 2 4 6 8

If you are used to something like NumPY in the Python programming language, this should seem very familiar. Indexing arrays is done with brackets. FreeMat uses 1-based indexes, so if you wanted to get the second value, you would use:

--> a(2)

You also can set the value at a particular index using the same notation. So you would change the value of the third element with:

--> a(3) = 5

These arrays all need to have the same data type. If you have need of a heterogeneous list of elements, this is called a cell array. Cell arrays are defined using curly braces. So, you could set up a name and phone-number matrix using:

--> phone = { 'Name1', 5551223; 'name2', 5555678 }

There are two new pieces of syntax introduced here. The first is how you define a string. In FreeMat, strings are denoted with a set of single quotation marks. So this cell array has two strings in it. The second new syntax item is the use of a semicolon in the definition of your array. This tells FreeMat that you're moving to a new row. In essence, you're now creating a matrix instead of an array.

Plotting in FreeMat is similar to plotting in R or matplotlib. Graphics functions are broken down into high-level and low-level functions. The most basic high-level function is plot(). This function is overloaded to try to do the right thing based on the input. A basic example would be plotting a sine function:

--> t = -63:64; --> signal = sin(2*pi*t/32); --> plot(t, signal)

This will pop up a new window to contain the results of the plot function (Figure 3). You then can use low-level functions to alter these plots. For example, you can set the title of your graph with the function:

--> title('This is my plot')

There are low-level functions to alter almost all of the elements of your plots.

One process that FreeMat tries to excel at is making the importation of external code easy on the end user. The import function is used to import a function from an external library and make it available to be used just like any other FreeMat function. The signature of the import function is:

import(libraryname,symbol,function,return,arguments)

This way, if you have some piece of code that is already written and tuned in C to get the maximum performance, you simply can import it and use it from within FreeMat with very little fuss.

Since FreeMat is as capable as MATLAB or Octave, you can assume that I've barely covered everything offered by FreeMat here. Hopefully, you have seen enough to spark your interest and will make some time to go and explore even more.

Resources

Main Web Site: freemat.sourceforge.net

FreeMat Tutorials: https://code.google.com/p/freemat/wiki/Tutorials

FreeMat Wiki: https://code.google.com/p/freemat/w/list

I've teased about Steam, speculated about Steam and even bragged about Steam finally coming to Linux. Heck, check out the screenshot for just a partial list of games already running natively under our beloved OS. Little did I know that the folks at Valve not only planned to support Linux, but they're also putting a big part of their future behind it as well!

Valve recently announced SteamOS (store.steampowered.com/livingroom/SteamOS), which is a Linux-based operating system designed from the ground up to play games. Steam games. The operating system will be free, and it also will be the OS running on Valve's next big thing, SteamMachines (store.steampowered.com/livingroom/SteamMachines). Although the hardware won't be available until sometime in 2014, the OS should be out before then.

Will Valve be the company to bridge the gap between computer gaming and console gaming? Will PC games translate to a television screen smoothly? Will the SteamOS's “game streaming” technology effectively bring the entire Steam library to Linux? I've learned enough not to make any predictions, but I can tell you it's an exciting prospect, and it's even more exciting because it's all running on Linux!

My Internet connection is unstable. I do realize ISPs generally claim some downtime is expected, and service is not guaranteed, and countless other excuses are common for intermittent service. I currently pay $120/month for business-class service, however, and I expect to get reliable Internet access on a regular basis. The most frustrating part is that the folks at my ISP don't believe I'm having intermittent problems, because every time they look, it seems fine.

Enter SmokePing.

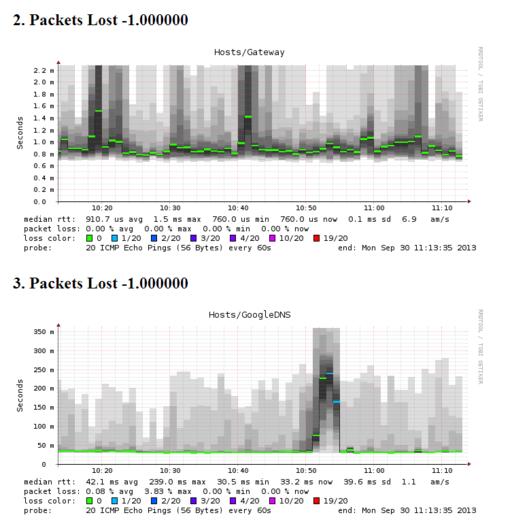

With past ISP problems, I've been able to run a continuous ping to an outside IP address and show the tech-support representative that I have packet loss. Unfortunately, a running ping command doesn't give a history of when the packets are lost. With SmokePing, not only is there a record of when packets are lost, but there's also a graphical representation of how many packets were lost, and from several IP addresses to boot.

Notice packet loss to the Google DNS server, but none to my gateway. So, the problem isn't with my house connection.

For my purposes, I keep track of pings to my local router, to the gateway provided by my ISP, and then a Google IP address and a foreign IP address. With that information, I usually not only can tell the ISP when the packets drop, but also whether it's an issue between me and its gateway or routing somewhere past my subnet. (For what it's worth, the problem is almost always between my router and my ISP's gateway, because there's some problem with its line coming to my office.)

If you need to prove packet loss, or if you just like to keep track of potential problems between hosts, SmokePing is an awesome uptime tracker that comes with colorful graphs and lots of useful information. For its incredible usefulness and straightforward approach to monitoring, SmokePing gets this month's Editors' Choice Award. Check it out at oss.oetiker.ch/smokeping.

It is wonderful how quickly you get used to things, even the most astonishing.

—Edith Nesbitt

There is nothing like the occasional outburst of profanity to calm jangled nerves.

—Kirby Larson, Hattie Big Sky, 2006

The art of being wise is the art of knowing what to overlook.

—William James

Laughter is inner jogging.

—Norman Cousins

Facing it, always facing it, that's the way to get through. Face it.

—Joseph Conrad