Miroslav Lichvar recently submitted some patches to improve the accuracy of the Linux system clock. Nowadays, the Linux clock generally is synchronized periodically with internet sources like everything else, but it's still nice to have a high degree of accuracy during the time in between synchronizations.

John Stultz liked the code, but he wanted to include Miroslav's test suite in the kernel as well, so that other developers could make sure future patches didn't spoil system clock accuracy. And, this turned out to be the biggest point of contention in the discussion thread.

Miroslav felt that his test suite—which really had been written only for his own use—was ugly, breakable and just bad news all around. However, John felt that its value outweighed all those things, and that its presence in the kernel would encourage others to improve the suite over time.

Eventually, they compromised. Miroslav wrote a new, more robust and maintainable test suite that was slower, less precise and less predictable than the original, but that still essentially did the job. It was a rare case where the quality of a feature takes a back seat to a developer's need to be able to hold his head up.

Luis R. Rodriguez, the firmware maintainer, noticed that bugs were creeping into the kernel firmware code, just because the folks submitting patches weren't sure who to cc. Patches, thus, were getting lost in the vast ocean of linux-kernel email. The patches themselves often would be reviewed and approved, but without the eyeballs that really could ferret out any troublesome breakages. Luis wanted to start a new mailing list, just for firmware.

The idea went nowhere, fast. Linus Torvalds said:

Boutique mailing lists are generally a bad thing. All it means is that there's an increasingly small “in group” that thinks that they generate consensus because nobody disagrees with their small boutique list, because nobody else even sees that small list. We should only have mailing lists if they really merit the volume, and are big enough that there are lots of users.

And, this judgment stood even though, as Luis pointed out, many device drivers had their own mailing lists, in spite of their having extremely low traffic. As Greg Kroah-Hartman put it, device drivers were not part of the core kernel infrastructure that everyone relied on. Firmware support, like other parts of the kernel, needed to be broadly scrutinized.

Of course, this was in conflict with Luis' original point—that patches were not being scrutinized enough because they'd get lost in the vastness of the main mailing list.

Even so, it seems that Linus, David, Greg and others want maintainers to find other solutions to that problem—perhaps by documenting a list of people to be cc'd on all patches within a given area of code—or perhaps something else. But, they definitely seem to want to avoid diluting the main linux-kernel mailing list traffic if at all possible.

Containers are weird. The whole idea is to pretend that you've got a virtual system running on top of a Linux box, just by isolating certain resources on that box and having them all act like they're a box of their own. You even could create virtual systems that are crippled or enhanced in bizarre ways, just because they match the specific requirements of a crazy new project you've got in mind. At the same time, the virtualization process itself creates a wide range of feature constraints and security caveats that always must be navigated properly. And, the whole implementation of containers is something that has to happen gradually over time because it's so nuanced and wide-ranging throughout the full breadth of the kernel, so that Linux has been approaching better and better virtualization during a course of years.

So, when David Howells wanted to implement a standardized container “object” that would wrangle all aspects of containers into a single, easy-to-use set of functions, he encountered nearly universal resistance.

In theory, it's a great idea. All the little niggling details of containers can cause odd security relationships, strange communication requirements and odd filesystem structures. Trying to smooth all of that out and give it a clean face seems like a natural next step, as containers become more and more robust.

But, James Bottomley, Jessica Frazelle, Aleksa Sarai and others felt that David was smoothing things about a bit too much and making too many assumptions about the kind of strange uses one might have for containers.

Ultimately, folks like Eric W. Biederman started proposing alternatives to David's approach that would be more flexible, and the discussion ended up being less about David's patches and more about how to implement the features that the people raising their objections seemed to want.

Eventually, some sort of container management system probably will go into the kernel, though there are also projects like Docker that attempt to fill that role. But as David remarked at a few different points, any in-kernel solution will be highly generic, more likely to be relied on by things like Docker, than to replace them.

This month's Editors' Choice award goes to the cool book streaming system BookSonic by Patrik Johansson. Johansson also created an Android app that connects to the BookSonic server, and it has some extra features the web interface lacks. Namely, it can save your place in a book, and it appears to have multiple speed playback.

Because it's based on the SubSonic system, there already are some great features included, such as caching for offline playback. I personally couldn't get the multi-speed playback to work, but it might be something I configured incorrectly on the server. Nevertheless, to experience BookSonic truly in all its glory, you must download the mobile client. It is a $3 purchase from the Google Play Store, but the source code is available on the author's GitHub page (https://github.com/popeen/Popeens-DSub), if you want to compile it yourself. Check it out!

Note: if you're using the Docker image to run the BookSonic server, be sure to use the following server URL when adding it to the Android app: http://your.docker.server.address:8080/booksonic.

The documentation doesn't mention the need for the trailing /booksonic, but without it, you'll get a connection error.

Much of the software I've covered through the years in this column has been focused on engineering, chemistry or physics. However, there is a growing number of software packages that are being written to apply computational resources to problems in biology. So in this article, I'm looking at one particular package for biology named Biogenesis. Biogenesis provides a platform where you can create entire ecosystems of lifeforms and see how they interact and how the system as a whole evolves over time.

You always can get the latest version from the project's main website (biogenesis.sourceforge.net), but it also should be available in the package management systems for most distributions. For Debian-based distributions, install Biogenesis with the following command:

sudo apt-get install biogenesis

If you do download it directly from the project website, you also will need to have a Java virtual machine installed in order to run it.

To start it, you either can find the appropriate entry in the menu of your desktop environment, or you simply can type biogenesis in a terminal window. When it first starts, you will get an empty window within which to create your world.

Figure 1. When you first start Biogenesis, you get a blank canvas so you can start creating your world.

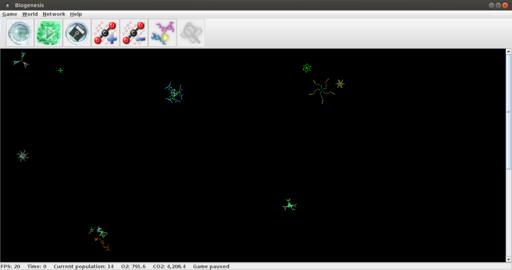

The first step is to create a world. If you have a previous instance that you want to continue with, click the Game→Open menu item and select the appropriate file. If you want to start fresh, click Game→New to get a new world with a random selection of organisms.

Figure 2. When you launch a new world, you get a random selection of organisms to start your ecosystem.

The world starts right away, with organisms moving and potentially interacting immediately. However, you can pause the world by clicking on the icon that is second from the right in the toolbar. Alternatively, you also can just press the p key to pause and resume the evolution of the world.

At the bottom of the window, you'll find details about the world as it currently exists. There is a display of the frames per second, along with the current time within the world. Next, there is a count of the current population of organisms. And finally, there is a display of the current levels of oxygen and carbon dioxide. You can adjust the amount of carbon dioxide within the world either by clicking the relevant icon in the toolbar or selecting the World menu item and then clicking either Increase CO2 or Decrease CO2.

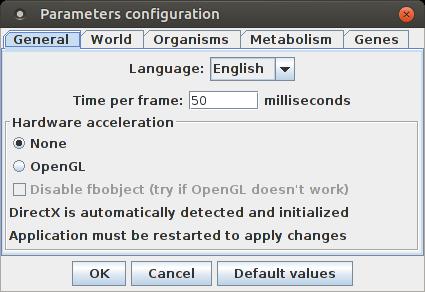

There also are several parameters that govern how the world works and how your organisms will fare. If you select World→Parameters, you'll see a new window where you can play with those values.

Figure 3. The parameter configuration window allows you to set parameters on the physical characteristics of the world, along with parameters that control the evolution of your organisms.

The General tab sets the amount of time per frame and whether hardware acceleration is used for display purposes. The World tab lets you set the physical characteristics of the world, such as the size and the initial oxygen and carbon dioxide levels. The Organisms tab allows you to set the initial number of organisms and their initial energy levels. You also can set their life span and mutation rate, among other items. The Metabolism tab lets you set the parameters around photosynthetic metabolism. And, the Genes tab allows you to set the probabilities and costs for the various genes that can be used to define your organisms.

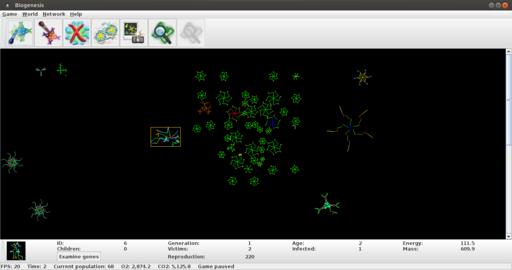

What about the organisms within your world though? If you click on one of the organisms, it will be highlighted and the display will change.

Figure 4. You can select individual organisms to find information about them, as well as apply different types of actions.

The icon toolbar at the top of the window will change to provide actions that apply to organisms. At the bottom of the window is an information bar describing the selected organism. It shows physical characteristics of the organism, such as age, energy and mass. It also describes its relationships to other organisms. It does this by displaying the number of its children and the number of its victims, as well as which generation it is.

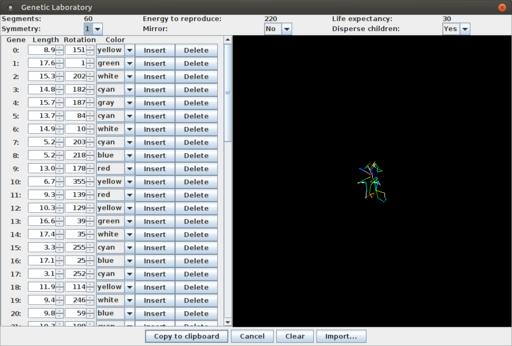

If you want even more detail about an organism, click the Examine genes button in the bottom bar. This pops up a new window called the Genetic Laboratory that allows you to look at and alter the genes making up this organism. You can add or delete genes, as well as change the parameters of existing genes.

Figure 5. The Genetic Laboratory allows you to play with the individual genes that make up an organism.

Right-clicking on a particular organism displays a drop-down menu that provides even more tools to work with. The first one allows you to track the selected organism as the world evolves. The next two entries allow you either to feed your organism extra food or weaken it. Normally, organisms need a certain amount of energy before they can reproduce. Selecting the fourth entry forces the selected organism to reproduce immediately, regardless of the energy level. You also can choose either to rejuvenate or outright kill the selected organism. If you want to increase the population of a particular organism quickly, simply copy and paste a number of a given organism.

Once you have a particularly interesting organism, you likely will want to be able to save it so you can work with it further. When you right-click an organism, one of the options is to export the organism to a file. This pops up a standard save dialog box where you can select the location and filename. The standard file ending for Biogenesis genetic code files is .bgg. Once you start to have a collection of organisms you want to work with, you can use them within a given world by right-clicking a blank location on the canvas and selecting the import option. This allows you to pull those saved organisms back into a world that you are working with.

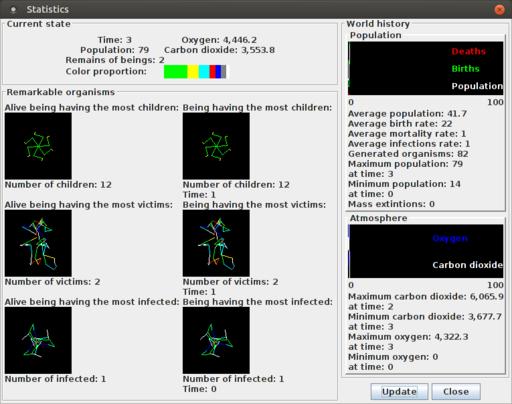

Once you have allowed your world to evolve for a while, you probably will want to see how things are going. Clicking World→Statistics will pop up a new window where you can see what's happening within your world.

Figure 6. The statistics window gives you a breakdown of what's happening within the world you have created.

The top of the window gives you the current statistics, including the time, the number of organisms, how many are dead, and the oxygen and carbon dioxide levels. It also provides a bar with the relative proportions of the genes.

Below this pane is a list of some remarkable organisms within your world. These are organisms that have had the most children, the most victims or those that are the most infected. This way, you can focus on organisms that are good at the traits you're interested in.

On the right-hand side of the window is a display of the world history to date. The top portion displays the history of the population, and the bottom portion displays the history of the atmosphere. As your world continues evolving, click the update button to get the latest statistics.

This software package could be a great teaching tool for learning about genetics, the environment and how the two interact. If you find a particularly interesting organism, be sure to share it with the community at the project website. It might be worth a look there for starting organisms too, allowing you to jump-start your explorations.

I have audiobooks from a variety of sources, which I've purchased in a variety of ways. I have some graphic audio books in MP3 format, a bunch of Audible books in their DRM'd format and ripped CDs varying from m4b (Apple format for books) to MP3 and even some OGG. That diversity makes choosing a listening platform difficult. In order to meet my idea of perfection, I need:

A system that plays any audio format.

A way to play books on multiple platforms, iOS Android and web browsers.

Current location stored and honored across platforms.

The ability to play audiobooks at different speeds.

An easy way to access my entire library remotely.

Several options come close. My favorite Android audiobook app, for instance, is “Listen”, available in the Play Store. But, it falls short on the multi-platform front and also on accessing books remotely. Audible itself will do most of what I need, but it doesn't allow importing remote books. And, traditional music players are out.

Honestly, Plex seems like the perfect platform for audiobooks. And although some people do use it, they're just kludging things. Plex doesn't natively support the concepts behind audiobooks, so the process isn't smooth at all. I'm honestly hoping that changes in the future, because it would be a perfect addition to an already amazing system. Thankfully, in the meantime, there's BookSonic.

You've probably heard of SubSonic, which is a music streaming server that allows you to do pretty much what I'm looking for with audiobooks, but it's strictly for music. Patrik Johansson (https://github.com/popeen) has forked SubSonic and created BookSonic, specifically modified to handle audiobooks. It even handles tagging and book art. Currently, the system isn't perfect, but it's closer than any other projects come to book nirvana, and if you use Docker, it's dead simple to get installed. A simple:

docker -d create \ --name booksonic \ -p 8080:8080 \ -v <path/to/storage/location/on/host>:/audiobooks \ -v <path/to/configuration/on/host>:/var/booksonic \ ironicbadger/booksonic

will get BookSonic running on your Docker host. Once it's installed, just head over to http://docker_host:8080 and log in as admin/admin. You can start the book scan, and fairly soon, your books will show up for you to start playing!

Many things about BookSonic do need work (syncing locations to the web client and so on), but it's a great start, and it's a wonderful way to access all your books in one place. Well, as long as you figure out how to strip the DRM from your Audible books anyway! BookSonic is such a great idea, and fills such a gaping hole, that even with its not-feature-complete release, it gets this month's Editors' Choice Award. For more details, head over to booksonic.org.

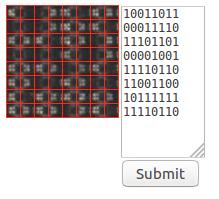

It's no secret that I love classic video games. Fortunately, thanks to emulation, many of the classic arcade games still can be enjoyed and forever will be available via digital copies of the ROM chips. Sadly, some older systems have protection, making them impossible to dump into ROMs properly. If the chips can't be dumped, how will you ever get a digital copy of the ROM data? Well, the folks over at the caps0ff.blogspot.com blog actually are disassembling the original chips and painstakingly transcribing the contents one bit at a time. They're literally looking at the chips and determining the 1s and 0s burned onto them.

Yes, there are a lot of chips. Yes, it takes a long time to copy the bits one by one. And yes, you can help. When a chip is stripped down literally to its bits (using various acid baths and so forth), it is scanned at high resolution. Then, pieces of the chips are put into a database over at https://cs.sipr0n.org, and people like you and me can transcribe the photos into 1s and 0s for the project!

Figure 1. This is a sample of the interface for identifying 1s and 0s on the scanned chips.

Having the underlying code doesn't automatically make your favorite non-dumpable games work in MAME or anything, but it's a crucial and difficult first step. It's also a fairly pricey step, because the chips need to be procured, and the chemicals need to be purchased. If you are passionate enough about preserving the old chips, you might consider donating money to the Caps0ff project as well. There's a great one-time donation site on Indiegogo with an explanation of the project: https://www.indiegogo.com/projects/caps0ff#. And, if you want to support them continually, recurring donations are handled at Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/user?u=4805718.

360° photos aren't a new concept, but if you're on Facebook, you'll notice they're more and more common. In fact, Facebook now will convert panoramic photos into a sort of 180° experience where you can drag the photo to see left and right. With a true 360° photo, you literally can spin the photo in a circle to see everywhere. If you're on a mobile device, the experience becomes a sort of VR thing, where if you turn while looking at the phone, it will pan the image for you, as if you're peering through into another world. Honestly, it's pretty cool.

In order to get the really nice 360° photos, you need a camera, or set of cameras, able to accomplish it. The easiest cameras are simple point (well, pointing is sort of moot) and shoot ones. The more complex multi-camera setups require photo stitching after the fact. I like the Ricoh Theta SC camera. It's a happy medium when it comes to quality, and the photos it takes are high enough resolution to appreciate the experience. There is a more expensive Ricoh Theta S, but the photo quality is similar, so unless you want to record 360° video, the SC is perfect.

Admittedly, connecting Android via Wi-Fi to the Theta camera is a pain in the butt, and it rarely works. There are several apps in the Play Store, and it's not clear which app to get. I ultimately skipped using my phone as a viewfinder and just stuck the camera in the air and snapped. Afterward, I downloaded the photos via USB to my computer and uploaded them from there. You can create a free account on theta360.com to host your photos, or you can upload them to Twitter, Facebook and so on. If you head to https://theta360.com/s/jCOnQ36A8nmw03lzQKgmQw7km, you can see a barn my wife and I looked at. The 360° experience really makes looking at photos more immersive, and I'm excited to see where the technology goes from here!

Put more trust in nobility of character than in an oath.

—Solon

You make me understand how wonderful it is for little lizards when they find that one special rock that's perfect for sunning themselves on. You make me lizard-happy.

—Randy K. Milholland

It is as hard to see one's self as to look backwards without turning around.

—Henry David Thoreau

I live in the present due to the constraints of the Space-Time Continuum.

—Hank Green

All that really belongs to us is time; even he who has nothing else has that.

—Baltasar Gracian