Always wanted to change the look of X Windows? Here are the tools to do it easily.

Do you ever wonder how some peoples' xclocks and xterms always start up with different colors than boring old black and white? Do you wish those Athena 3-D widgets (discussed in Linux Journal, issue 15) looked a bit more like the Motif ones they are supposed to emulate? Through the magic of something called X Resources, you can make all this happen—and a lot more.

Resources may look confusing and complex at first glance, like something only a programmer with a mean streak would foist upon the unwitting user. It's true that resources are very closely tied to X programming, which is why they can appear so arcane. However, with a little practice, you can customize applications to suit your own personal preferences, and kiss “vanilla X” goodbye forever.

Color has already been mentioned, but to dismiss resources as a simple color control mechanism would be a mistake. Don't like an application's choice of fonts? Change them. Want to change the way the cursor appears? You can do that too.

Resources can even be used to modify the entire behaviour of an application, from the appearance and labels of buttons and pull-down menus, to the actual functions that these items call in the program. For instance, if you think that the “Quit” label on a button is too bland, you can easily substitute “Kill”, or something even more imaginative.

X Resources are stored in several locations. Applications often have a default set of resources that are stored in a file in the /usr/lib/X11/app-defaults directory. For example, you will find resource files for both xterm and xload in that directory. Notice the files usually have the first two letters capitalized, i.e. XTerm, and XLoad. While this is only a de-facto standard, it is related to the applications class name, which we'll get to later.

Besides these application-specific files, there are two other files in which you can store resources. If you have a file in your home directory called .Xdefaults, it will be loaded when your X session starts (either through xdm or startx), replacing any system-wide resources that might have been defined (stored in /usr/lib/X11/Xdefaults). A second file, .Xresources, doesn't replace the system defaults but instead is merged with them. For that reason, you probably want to use this file for your own resources instead of .Xdefaults.

Resources are specified in one of the following formats:

name*variable: valuename.variable.variable: value

Resources are case sensitive, and you should be sure that there is at least a space or a tab after the colon, before the value specified. The first format listed, which utilizes the * separator (called loose binding), is used to indicate that all resources of a program with name name and variable variable are to acquire value value. For instance, the resource

Xedit*font: 7x14

will cause xedit to use a 7x14 fixed font for everything, including the main window and the menus. (We will see how to find resource names later in the article—take them on faith for now.) But what if you only want to change the font in a particular area of a program? In that case, the . notation (called tight binding) would be used. This notation allows you to be more specific than loose binding allows:

Xedit.Paned.Label.font: fixed

will make two labels in xedit use the fixed font. However, the default font (7x14, as set by the first resource) will be used everywhere else. Note that although the first resource applies to every font resource in the Xedit program, including those two labels, the second resource is the one used for those labels because it is more specific. More specific resources are always used in preference to less specific resources.

Resources, and the widgets they modify, have a hierarchical nature. “What's a widget?” you ask. Widgets are the basic building blocks, or objects, of X programs. Some example widgets with which everyone is familiar: scrollbars, text-entry fields, buttons, and checkboxes. In the above resource, the Label widget is a “child” of the Paned widget, which is a “child” of Xedit. This will become more clear when the editres program is introduced below.

One other note before we continue: a distinction must be made between classes and instances of a particular class. In the above resource, Label specifies any instance of the widget class Label. There are two that match the specification, whose names are bc_label and labelWindow. All classes begin with a capital letter by definition; Label is the class, and bc_label and labelWindow, which start with lower case letters, are the instances of that class.

You can specify instances as well as classes, so that only one particular widget is affected; you can add the following resource:

Xedit.paned.bc_label.font: 7x14

which will set the font for one of the two Label widgets back to 7x14—it is more specific than the previous resource.

It is usually more convenient to set the resources for an entire class of widgets than for an individual instance, as you typically want to make the entire application look consistent.

Several times, you've been told to add or modify a resource. How is this accomplished? The X distribution provides several programs you can use to add, modify, and view resources. The most simple method (but perhaps the most difficult) is to specify the resource for a program as an argument when the program is started. Most well-behaved X programs accept the xrm command line option for adding or modifying a single resource. The format works like this:

-xrm "resource"

Specifying resources on the command line can become tedious, to say the least. X provides considerably more sophisticated mechanisms to modify and examine resources. The most simple of these is xrdb. Xrdb is a command line utility that can load, query, and merge resources. Here are some of the common command line options:

-load filename Load the resources contained in filename into the resource database. Replaces any resources currently in the database with new values if they are specified in the file.

-merge filename Performs much like the load option, but only loads those resources which are not already modified. Nothing currently in the resource database that is encountered in the file will be loaded.

-query Show the resource database that is currently in use. Only those resources that have been modified are displayed. If all resources were displayed (including defaults), then you would probably have much more information than you expected.

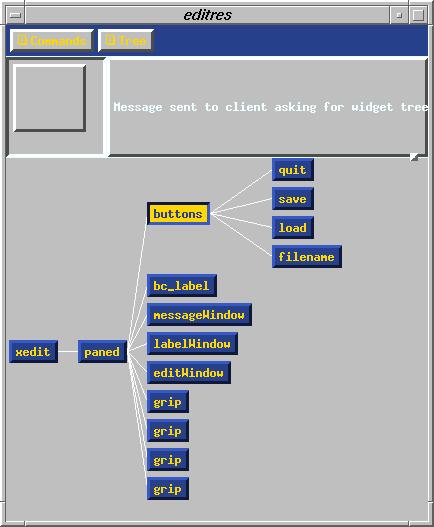

Another very useful program that comes with the X distribution is editres. Editres can be used to interactively modify the resources of a particular program. After starting editres, pull down the “Commands” menu, select “Get Widget Tree”, and then click on the application you want to examine or modify. Now you should see something like what is pictured in Figure 1 (the actual hierarchy pictured is for xedit). Note that it won't look exactly like Figure 1, because I've modified my resources for editres.

Figure 1. editres, an interactive X resource editor

All widgets are laid out in a tree-like fashion, with the parent widgets on the left, and their children progressing to the right. Lines connect children to parents. You can use the box in the upper-left corner of editres to move the display around if the widget tree is larger than the window itself.

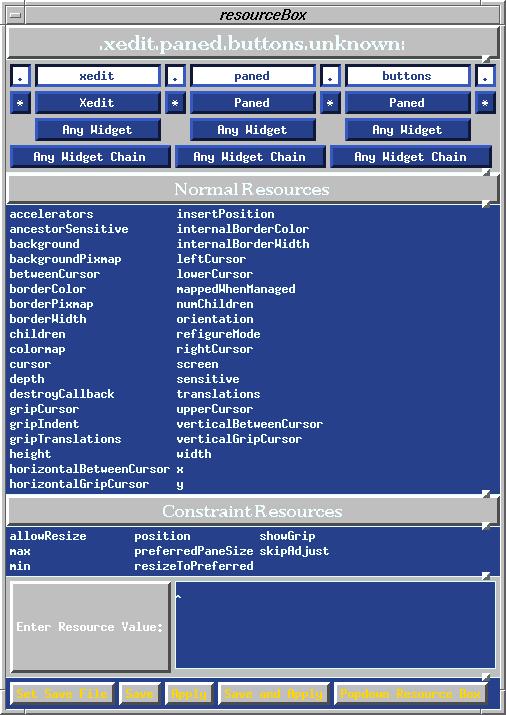

Using the “Tree” menu, you can switch between class and instance names and select certain widgets in particular. If you want to modify the resources of one particular widget, select it by clicking on it once with the left mouse button, and then, from the “Commands” menu, choose “Show Resource Box”. A popup box with all the available resources for the widget selected will be displayed, as shown in Figure 2. In the Resource Box, select a resource with the mouse, and then enter a value for the resource in the text field below. This is perhaps the easiest way to both find the names of the resources and experiment with setting them to different values.

Figure 2. Ascreen from editres showing the resource display screen

You can also make the resource string more loosely or tightly bound by adjusting which fields are highlighted at the top of the popup window. When you are ready to see the results of your changes, push the “Apply” button at the bottom of the window.

More detailed help with editres can be found on the editres manual page.

No article on X resources would be complete without detailed examples of how they can be used. To do this, we'll take a look at one simple X client—xclock—and then at a whole widget set—the Athena widgets (which are a stock part of any X11 distribution).

Let's try a couple of things with xclock. You can either make these changes with editres, so you can view them interactively, or you can add them to your .Xresources file, which you'll need to merge with xrdb. Remember, whenever you make changes to the resource database, the clients affected need to be restarted in order for the changes to take effect. If you think the normal black and white scheme of the clock is too dull, consider the following:

*xclock.foreground: steelblue*xclock.hands: steelblue *xclock.background: ivory

That should give you some ideas for starters. For a more extensive change in appearance, try:

*xclock.analog: 0

This will make the clock display in a digital fashion. Specifying 1 as the value for this resource will reset it to the normal analog display.

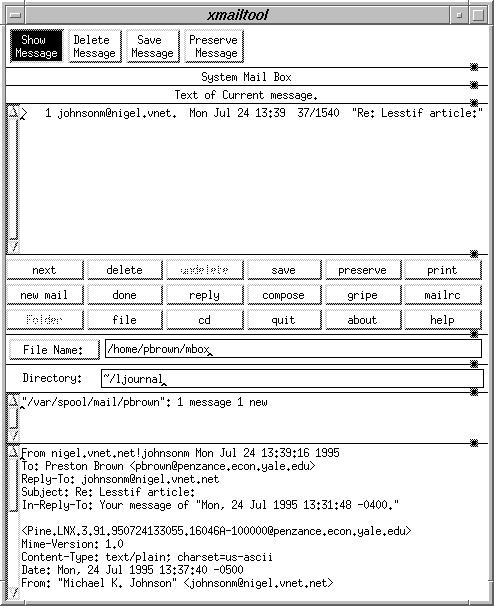

Let's go a step further. In the July, 1995 issue of Linux Journal, the Xaw3D widgets were introduced. The purpose of these widgets is to give the default Athena widgets a more three-dimensional look and feel. However, with no default resources, programs still can look washed out and dull. This is because no default colors have been specified for the widgets, so programs that don't change these resources explicitly will display them in black and white with unattractive, dithered shadowing. See Figure 3 for an example of this.

Figure 3. A “vanilla” xmailtool

A set of resources which make the Xaw3D widgets appear more like the popular Motif widgets appear in Listing 1.

Listing 1

! Good Xaw3d Defaults*customization: -color *shadowWidth: 3 *Form.background: gray75 *MenuButton.background: gray75 *SimpleMenu.background: gray70 *TransientShell*Dialog.background: gray70 *Command.background: gray75 *Label.background: gray75 *ScrollbarBackground: grey39 *Scrollbar*background: gray75 *Scrollbar*width: 15 *Scrollbar*height: 15 *Scrollbar*shadowWidth: 2 *Scrollbar*cursorName: top_left_arrow *Scrollbar*pushThumb: false *shapeStyle: Rectangle *beNiceToColormap: False *SmeBSB*shadowWidth: 3 *highlightThickness: 0 *topShadowContrast: 40 *bottomShadowContrast: 60 ! fix up a few of the default X clients who ! now look silly *xclock*shadowWidth: 0 *xload*shadowWidth: 0 *xcalc*shadowWidth: 0

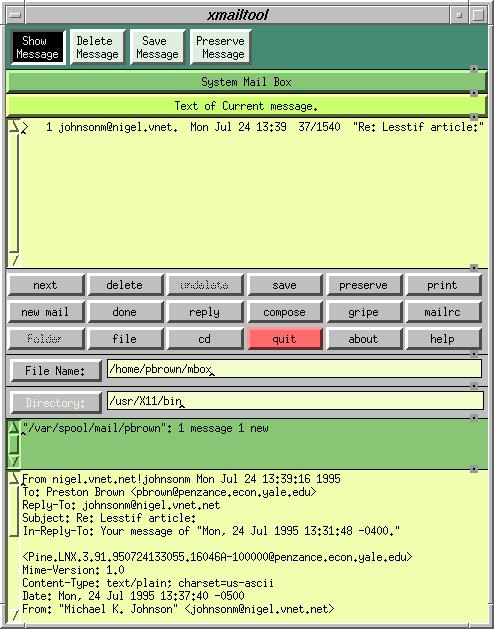

The first resource tells all programs that color is available and should be used. Then, the shadow width for all Athena widgets is set to 3 (which looks like Motif). Default colors are then selected for most of the common widgets (buttons, scrollbars, and the like), and shadow contrast levels are set. Finally, shadows on a few X clients is a bit overkill, so shadowWidth is reduced to 0 for these. Figure 4 shows how the program now looks more aesthetically pleasing as a result of these modifications.

Figure 4. xmailtool after resource changes

This should get you started. X resources are one of the most important aspects of X programs in general, so a basic understanding of them is essential—not only for using and customizing X programs, but also writing them. You should now be able to discover the resources hiding behind your own favorite programs, and it would be good practice for you to apply the techniques in this article to a different program of your own choosing right now. Remember this while you are tinkering with X resources: X may not be as simple to configure as MS Windows, but it is much more powerful.

Enjoy!