Linux servers and applications are being used in Denmark to provide an interactive teletext system for TV viewers and to offer phones and movies to hospital patients.

In a modest building outside Copenhagen, Grundig TV-Communications engineers Niels Svennekjaer and Peter Hansen tend to the information needs of Danish hospital patients and TV viewers, monitoring and making fixes to Linux-based applications running on PCs. In the basement, a Linux server hosts an interactive teletext system. Television viewers phone this system and navigate a Raima database of classified ads, horoscopes, job listings and other information, entering their choices through the telephone keypad and receiving text responses on their TV screens. Already, Denmark's TV2 nation-wide broadcaster and several local stations have adopted this technology; the government unemployment bureau recently made it the official channel for job listings.

In a hardware-cluttered office upstairs, Svennekjaer phones in via modem and fine-tunes a Linux server at a local hospital. This application makes amenities such as phones and pay-per-view movies available in Denmark's highly efficient (yet somewhat spartan) hospital system and has already been sold to five hospitals in Scandinavia. Grundig TV-Communications' vision includes taking this system into Poland and the Baltic nations.

Is the quintessential hacker's operating system making inroads at one of the Europe's largest electronics manufacturers? At Grundig TV-Communications, a Danish outpost of the large German firm Grundig AG, Linux has become the standard platform for information-on-demand applications. Grundig TV-Communications likes the freely distributable operating system's low cost, robustness and the availability of tools. They are also impressed by its support—not from a raft of engineers on call at a vendor's headquarters, but from the multitude of other Linux users who can be reached via the Internet.

Grundig has chosen Linux for its new hospital and broadcasting systems and will likely move to Linux with its core product, a hotel teletext system serving some 200,000 rooms in Europe and Asia. It has also standardized on Raima's embedded database as the data management component in its applications. Both the hospital and broadcasting applications use Raima Database Manager++, a low-level database tailored to the needs of C and C++ programmers. In the next step of their evolution, these products will move to a client/server architecture with Raima's Velocis Database Server. Svennekjaer believes this redesign will better support the heavier load of concurrent users and more complex queries the applications are beginning to experience.

Teletext is largely unknown in the United States, but it is widely used in Europe, where viewers obtain sports scores, news updates and other text by tuning into special channels. This service is supported by a band of the broadcast spectrum that governments set aside for teletext and other special purposes, such as remote equipment maintenance.

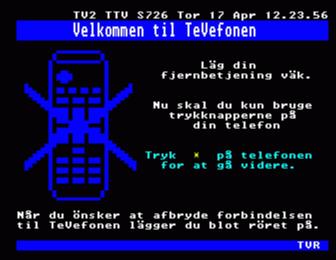

Grundig TV-Communications goes well beyond these usually passive teletext services by adding a dimension of user interaction. When viewers call into the server, a personal “page” appears on their screen. From that page they begin navigating the Raima database. A user might first request all real estate listings, then “drill down” to two bedroom, waterfront holiday homes on the Jutland peninsula. At TV2 the resulting data streams are sent from a Pentium server PC to one of 16 inserter PCs placed in TV station broadcast towers at different locations in the country, where they are mixed with the broadcast signal.

The revenue from this application comes from content providers, who pay for their data to be accessible in Grundig's Linux server. Television advertisers frequently provide teletext codes for obtaining more information, and the server's peak loads occur when commercials are particularly successful in drawing viewers. The server and database respond to requests for some 200,000 pages of information per day.

For the hospital application, Grundig TV-Communications provides tape-deck-sized panels which sit next to the patient's bed. When they check in, patients receive “smart cards” to insert in these panels to activate their personal television, telephone and radio accounts. Listening to the radio is free, but patients pay by the minute for phone and TV and per-movie for videos. Most are happy to pay. Danish medicine is of high quality, but the government-run system provides few amenities—nurses wheeling trolleys of shared phones are still a common sight in many hospitals, according to Svennekjaer.

A Linux-based application controls access to these services and monitors patient usage and billing. Grundig shares the revenues from this application with two partner companies which handle marketing, installation and billing. So far, hospitals earn no money from the application, but they benefit from having happier patients.

The multi-user, multi-tasking demands of these applications made Unix a natural choice of operating systems, Svennekjaer says. Interactive Unix, their first platform, was produced by an independent vendor, sold to Kodak, then sold to Sun. The Grundig team felt this platform's future was uncertain and decided to switch. For cost reasons, they wanted to use PCs, so they evaluated SCO and Solaris. About the same time, Svennekjaer says, some of his friends were “playing around” with Linux version 0.99 at the Aalborg University Center in Denmark. They recommended that he try this unknown (to Svennekjaer) Unix. “We ported our application to Linux in one week, and it worked. And it was free!” Svennekjaer recalls.

But did the freely distributable operating system make sense for commercial applications targeted at hundreds of deployment sites? When the Grundig TV-Communications team weighed the risks and rewards, Linux looked better than the alternatives. First, there was the price tag of approximately $2,000 per site for a commercial release of Unix versus $20 apiece for CD-ROMs with the complete Linux system plus ample tools, add-ons and enhancements.

And what about the frequently-voiced concern that Linux is an “unsupported” operating system? The idea of support, it turns out, is relative for developers working far away from the OS vendors—or perhaps for any developers making especially complex system demands. Svennekjaer notes that in the past he relied on local distributors of commercial software products for help. When his dealer couldn't help him with a stack overflow, the $2,000 he spent on a supposedly “supported” product started looking like money wasted.

In contrast, with Linux “we get the source code, so we can address problems directly when they come up,” he says. In addition, when particularly difficult issues arise, Svennekjaer posts his questions to one of the many Linux newsgroups on the Internet. “Usually the next day we have five answers” from Linux programmers around the world, many of whom are intimately familiar with the source code.

For example, Svennekjaer uses a RAID with four hotplug/hotswap disks as backup for the teletext application, in case its hard drive fails. Distributed Processing Technologies (DPT), the manufacturer of the SCSI disk-controller for the RAID, did not provide a Linux driver at that time, but one was included with the kernel source of Svennekjaer's Linux distribution. However, after moving to an updated version of the disk-controller, Svennekjaer experienced problems with the old driver. So he tracked down the driver's author, Michael Neuffer, from an e-mail address listed in the driver source, obtained an updated version and was back on track within days. (Since that time, DPT has begun distributing a Linux driver developed by a third party.)

According to Svennekjaer, the problem with Linux tools is not lack of availability, it's that there are so many that it's distracting—CAD/CAM programs, ray-tracing software, biomolecular analysis programs, diagram editors, multi-user games, web servers and other interesting free or demo packages announced in comp.os.linux.announce.

While Svennekjaer downloads many of his Linux-based tools for free, his firm has opted for commercial database technology, first with Raima Database Manager++ and later with Velocis Database Server, an SQL client/server DBMS that evolved from the RDM++ technology. Velocis and RDM++ are unique in that they support database architectures using the relational database model, network database model and combinations of both models. This flexibility can be useful. Relational “keyed” data access is typically better for finding randomly selected records, while the network model is faster when retrieving related records or drilling down through hierarchical data, as is often the case for users of the teletext application.

The current applications based on RDM++ enable multiple processes to access the database. The move to client/server is intended to support even heavier usage, as both the hospital and teletext systems scale up to serve thousands of users, and as these users generate more complex queries.

Client/server architecture will centralize database processing on the server, thus reducing network traffic. It will also improve concurrency, the ability of multiple processes to share data. In databases, concurrency is regulated by locking whereby a certain portion of the database is made off limits to other processes while a single process accesses it. Like most file-server architecture database management systems, Raima Database Manager++ provides file-level or table-level locking—a data file or database table is the typical unit that is locked. Velocis, on the other hand, provides row-level locking, in which a much smaller unit (data files or tables are made up of many rows) is made unavailable to other processes. It also includes features for protecting the integrity of transactions, such as “roll-forward recovery”, in which related changes to the database are completed only as a unit, even if the system goes down during a transaction.

In the future, the teletext application will offer more demanding services, like providing a calculator so a user can figure out the monthly payments on a car with a specific price, interest rate and down payment. Grundig TV-Communications also wants to let users customize their queries. In the past, the Grundig team has “hard-wired” its calls to the database, coding them in C function calls that are embedded in the application. However, the introduction of Velocis will add SQL capabilities to the system. SQL is a high-level database query language that can be used to give end-users the ability to define their own queries.

For example, a user might want to view listings for all cars with air conditioning in a particular price range and within a particular geographic area. As more possible variables exist for a search, much more complex queries can be defined. Offering SQL will let users search using their own criteria, eliminating the Grundig TV Communications' engineers need to define all queries in advance. It's one more step toward making information truly available on demand.

Grundig TV-Communications Engineer Niels Svennekjaer can be contacted at nrs@gtv.dk. Lars Teil, who manages the Linux teletext system at TV2, can be reached at late@tv2.dk.