Ease your creation and maintenance of web pages using this handy pre-processor called m4.

It's amazing how easy it is to write simple HTML pages—and the availability of WYSIWYG (what you see is what you get) HTML editors like Netscape Gold lulls one into a mood of “don't worry, be happy”. However, managing multiple, inter-related pages of HTML rapidly gets very difficult. I recently had a slightly complex set of pages to put together, and I started thinking, “there has to be an easier way.”

I immediately turned to the WWW and looked up all sorts of tools—but quite honestly I was rather disappointed. Mostly, they were what I would call “typing aids”—instead of having to remember arcane incantations like <a href="link"7gt;text</a> text, you are given a button or a magic keychord like alt-ctrl-j which remembers the syntax and does all the typing for you.

Linux to the rescue—since HTML is built as ordinary text files, the normal Linux text management tools can be used. This includes revision control tools such as rcs and the text manipulation tools like awk, Perl, etc. These tools offer significant help in version control and managing development by multiple users as well as automating the process of displaying information from a database (the classic grep |sort |awk pipeline).

The use of these tools with HTML is documented elsewhere, e.g., Jim Weirich's article in Linux Journal Issue 36, April 1997, “Using Perl to Check Web Links”. I highly recommend this article as yet another way to really flex those Linux muscles when writing HTML.

What I will cover here is work I've done recently using the pre-processor m4 to maintain HTML. The ideas can very easily be extended to the more general SGML case.

I decided to use m4 after looking at various other pre-processors including cpp, the C front-end, which is perhaps a little too C-specific to be useful with HTML. m4 is a generic and clean macro expansion program, and it's available under most Unices including Linux.

Instead of editing *.html files, I create *.m4 files with my favourite text editor. These files look something like the following:

m4_include(stdlib.m4) _HEADER(`This is my header') <P>This is some plain text<P> _HEAD1(`This is a main heading') <P>This is some more plain text<P> _TRAILER

The format is just HTML code, but you can include files and add macros rather like in C. I use a convention that my new macros are in capitals and start with an _ character to make them stand out from HTML language and to avoid name-space collisions.

The m4 file is then processed as follows to create an .html file using the command:

m4 -P <file.m4 >file.html

This process is especially easy if you create a makefile to automate these steps in the usual way. For example:

.SUFFIXES: .m4 .html

.m4.html:

m4 -P <$*.m4 >$*.html

DEFault: index.html

*.html: stdlib.m4

all: default PROJECT1 PROJECT2

PROJECT1:

(cd project2; make all)

PROJECT2:

(cd project2; make all)

Some of the most useful commands in m4 are listed here with their

cpp equivalents shown in parentheses:

m4_include: includes a common file into your HTML (#include)

m4_define: defines an m4 variable (#define)

m4_ifdef: a conditional (#ifdef)

m4_changecom: change the m4 comment character (normally #)

m4_debugmode: control error diagnostics

m4_traceon/off: turn tracing on and off

m4_dnl: comment

m4_incr, m4_decr: simple arithmetic

m4_eval: more general arithmetic

m4_esyscmd: execute a Linux command and use the output

m4_divert(i): This is a little complicated, so skip on first reading. It is a way of storing text for output at the end of normal processing. It will come in useful later, when we get to automatic numbering of headings. It sends output from m4 to a temporary file number i. At the end of processing, any text which was diverted is then output, in the order of the file number i. File number -1 is the bit bucket and can be used to comment out chunks of comments. File number 0 is the normal output stream. Thus, for example, you can use m4_divert to divert text to file 1, and it will only be output at the end.

In many “nests” of HTML pages, each page shares elements such as a button bar containing links to other pages like this:

[Home] [Next] [Prev] [Index]

This is fairly easy to create in each page. The trouble is that if you make a change in the “standard” button-bar then you have the tedious job of finding each occurrence of it in every file and manually making the changes. With m4 we can more easily do this job by putting the shared elements into an m4_include statement, just like C.

Let's also automate the naming of pages by putting the following lines into an include file called button_bar.m4:

m4_define(`_BUTTON_BAR', <a href="homepage.html">[Home]</a> <a href="$1">[Next]</a> <a href="$2">[Prev]</a> <a href="indexpage.html">[Index]</a>)

and then these lines in the document:

m4_include button_bar.m4 _BUTTON_BAR(`page_after_this.html', `page_before_this.html')The $1 and $2 parameters in the macro definition are replaced by the strings in the macro call.

It is troublesome to have items change in multiple HTML pages. For example, if your e-mail address changes, you need to change all references to it to the new address. Instead, with m4 you can put a line like the following in your stdlib.m4 file:

m4_define(`_EMAIL_ADDRESS', `MyName@foo.bar.com')

and then just put _EMAIL_ADDRESS in your m4 files.

A more substantial example comes from building strings with multiple components, any of which may change as the page is developed. If, like me, you develop on one machine, test out the page and then upload to another machine with a totally different address, then you could use the m4_ifdef command in your stdlib.m4 file (just like the #ifdef command in cpp). For example:

m4_define(`_LOCAL') ... m4_define(`_HOMEPAGE', m4_ifdef(`_LOCAL', `//127.0.0.1/~YourAccount', `http://ISP.com/~YourAccount')) m4_define(`_PLUG', `<A HREF="http://www.ssc.com/linux/"> <IMG SRC="_HOMEPAGE/gif/powered.gif" ALT=<"[Linux Information]"> </A>')

Note the careful use of quotes to prevent the variable _LOCAL from being expanded. _HOMEPAGE takes on different values according to whether the variable _LOCAL is defined or not. This definition can then ripple through the entire project as you build the pages.

In this example, _PLUG is a macro to advertise Linux. When you are testing your pages, use the local version of _HOMEPAGE. When you are ready to upload, remove or comment out the _LOCAL definition in this way:

m4_dnl m4_define(`_LOCAL')

... and then re-make.

Styles built into HTML include things like <EM> for emphasis and <CITE> for citations. With m4 you can define your own new styles like this:

m4_define(`_MYQUOTE', <BLOCKQUOTE><EM>$1</EM></BLOCKQUOTE>)

If, later, you decide you prefer <STRONG> instead of <EM>, it is a simple matter to change the definition. Then, every _MYQUOTE paragraph falls into line with a quick make.

The classic guides to good HTML writing say things like “It is strongly recommended that you employ the logical styles such as <EM>...</EM> rather than the physical styles such as <I>...</I> in your documents.” Curiously, the WYSIWYG editors for HTML generate purely physical styles. Using the m4 styles may be a good way to keep on using logical styles.

I don't depend on WYSIWYG editing (having been brought up on troff) but all the same I'm not averse to using help where it's available. There is a choice (and maybe it's a fine line) to be made between:

<BLOCKQUOTE><PRE><CODE>Some code you want to display. </CODE></PRE></BLOCKQUOTE>

and:

_CODE(Some code you want to display.)In this case, you would define _CODE like this:

m4_define(`_CODE', <BLOCKQUOTE><PRE><CODE>$1</CODE></PRE></BLOCKQUOTE>)Which version you prefer is a matter of taste and convenience although the m4 macro certainly saves some typing. Another example I like to use, since I can never remember the syntax for links, is:

m4_define(`_LINK', <a href="$1">$2</a>)Then, instead of typing:

<a href="URL_TO_SOMEWHERE">Click here to get to SOMEWHERE </a>I type:

_LINK(`URL_TO_SOMEWHERE', `Click here to get to SOMEWHERE')

m4 has a simple arithmetic facility with two operators m4_incr and m4_decr. This facility can be used to create automatic numbering, perhaps for headings, for example:

m4_define(_CARDINAL,0) m4_define(_H, `m4_define(`_CARDINAL', m4_incr(_CARDINAL))<H2>_CARDINAL.0 $1</H2>') _H(First Heading) _H(Second Heading)

This produces:

<H2>1.0 First Heading</H2> <H2>2.0 Second Heading</H2>

For simple date stamping of HTML pages, I use the m4_esyscmd command to maintain an automatic timestamp on every page:

This page was updated on m4_esyscmd(date)

which produces:

This page was last updated on Fri May 9 10:35:03 HKT 1997

Using m4 allows you to define commonly repeated phrases and use them consistently. I hate repeating myself because I am lazy and because I make mistakes, so I find this feature an absolute necessity.

A good example of the power of m4 is in building a table of contents in a big page. This involves repeating the heading title in the table of contents and then in the text itself. This is tedious and error-prone, especially when you change the titles. There are specialised tools for generating a table of contents from HTML pages, but the simple facility provided by m4 is irresistible to me.

The following example is a fairly simple-minded table of contents generator. First, create some useful macros in stdlib.m4:

m4_define(`_LINK_TO_LABEL', <A HREF="#$1">$1</A>) m4_define(`_SECTION_HEADER', <A NAME="$1"><H2>$1</H2></A>)

Then define all the section headings in a table at the start of the page body:

m4_define(`_DIFFICULTIES', `The difficulties of HTML') m4_define(`_USING_M4', `Using <EM>m4</EM>') m4_define(`_SHARING', `Sharing HTML Elements Across Several Pages')Then build the table:

<UL><P> <LI> _LINK_TO_LABEL(_DIFFICULTIES) <LI> _LINK_TO_LABEL(_USING_M4) <LI> _LINK_TO_LABEL(_SHARING) <UL>Finally, write the text:

... _SECTION_HEADER(_DIFFICULTIES) ...The advantages of this approach are twofold. If you change your headings you only need to change them in one place, and the table of contents is then automatically regenerated. Also, the links are guaranteed to work.

The table of contents generator that I normally use is a bit more complex and requires a bit more study, but it is much easier to use. It not only builds the table, but it also automatically numbers the headings on the fly—up to four levels of numbering (e.g., section 3.2.1.3), although this can be easily extended. It is very simple to use as follows:

Where you want the table to appear, call Start_TOC.

At every heading use _H1(`Heading for level 1') or _H2(`Heading for level 2') as appropriate.

After the last line of HTML code (probably </HTML>), call End_TOC.

The code for these macros is shown in Listing 1. One restriction is that you should not use diversions (i.e., m4-divert) within your text, unless you preserve the diversion to file 1 used by this TOC generator.

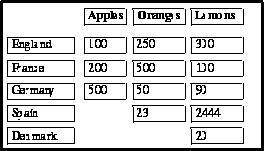

Other than Tables of Contents, many browsers support tabular information. Here are some funky macros as a short cut to producing these tables. First, an example (see Figure 1) of their use:

<CENTER> _Start_Table(BORDER=5) _Table_Hdr(,Apples, Oranges, Lemons) _Table_Row(England, 100,250,300) _Table_Row(France,200,500,100) _Table_Row(Germany,500,50,90) _Table_Row(Spain,,23,2444) _Table_Row(Danmark,,,20) _End_Table </CENTER>

Figure 1. Example Table

Unfortunately, m4 needs some taming. A little time spent on familiarisation will pay dividends. Definitive documentation is available (for example, in the Emacs info documentation system) but, without being a complete tutorial, here are a few tips based on my experiences.

m4's quotation characters are the grave accent ` which starts the quote, and the acute accent ' which ends it. It may help to put all arguments to macros in quotes, for example:

_HEAD1(`This is a heading')

The main reason for using quotes is to prevent confusion if commas are contained in an argument to a macro, since m4 uses commas to separate macro parameters. For example, the line _CODE(foo, bar) would put the foo in the HTML output but not the bar. Use quotes in the line _CODE(`foo, bar'), and it works properly.

The biggest problem with m4 is that some versions of it swallow key words that it recognises, such as include, format, divert, file, gnu, line, regexp, shift, unix, builtin and define. You can protect these words by putting them in single quotes, for example:

Smart people `include' Linux in their list of computer essentials.

The trouble is, this is both inconvenient and easy to forget.

A safer way to protect keywords (my preference) is to invoke m4 with the -P or --prefix-builtins option. Then all built-in macro names are modified so that they all begin with the prefix m4_ and ordinary words are left as is. For example, using this option, one would write m4_define instead of define (as shown in the examples in this article). One hitch is that not all versions of m4 support this option—most notably some PC versions under MS-DOS.

Comment lines in m4 begin with the # character—everything from the # to the end of the line is ignored and output unchanged. If you want to use # in the HTML page, you must quote it like this: `#'. Another option (my preference) is to change the m4 comment character to something exotic with a line like this:

m4_changecom(`[[[[')

and not have to worry about # symbols in your text.

If you want to use comments in the m4 file but not have them appear in the final HTML file, use the macro m4_dnl (dnl = Delete to New Line). This macro suppresses everything until the next newline character.

m4_define(_NEWMACRO, `foo bar') m4_dnl This is a comment

Yet another way to have source code ignored is the m4_divert command. The main purpose of m4_divert is to save text in a temporary buffer for inclusion in the file later—for example, in building a table of contents or index. However, if you divert to “-1”, it just goes to limbo-land. This option is useful for getting rid of the whitespace generated by the m4_define command. For example:

m4_divert(-1) diversion on m4_define(this ...) m4_define(that ...) m4_divert diversion turned off

Another tip for when things go wrong is to increase the number of error diagnostics that m4 outputs. The easiest way to do this is to add the following to your m4 file as debugging commands:

m4_debugmode(e) m4_traceon ... buggy lines ... m4_traceoff

It should be noted that HTML 3.0 does have an include statement that looks like this:

<!--#include file="junk.html" -->

However, the HTML include has the following limitations:

The work of including and interpreting the include is done on the server-side before downloading and adds overhead as the server has to scan files for include statements.

Most servers (especially public ISPs) deactivate this feature because of the large overhead.

Include is all you get—no macro substitution, no parameters to macros, no ifdef, etc., as with m4.

There are several other features of m4 that I have not yet exploited in my HTML ramblings so far, such as regular expressions. It might be interesting to create a “standard” stdlib.m4 for general use with nice macros for general text processing and HTML functions. By all means download my version of stdlib.m4 as a base for your own hacking. I would be interested in hearing of useful macros, and if there is enough interest, maybe a Mini-HOWTO could evolve from this article.

There are many additional advantages to using Linux to develop HTML pages, far beyond the simple assistance given by the typical typing aids and WYSIWYG tools. Certainly, I will go on using m4 until HTML catches up—I will then do my last make and drop back to using pure HTML. I hope you enjoy these little tricks and encourage you to contribute your own.