One of the great things we can do with Linux and GNU tools is build an environment for cross-platform development. The perfect example for cross-platform development using Linux is the Palm Pilot development tools for Linux. In this article, I will explain the tools and methods you should use in order to program this small but very smart machine from your own Linux machine.

The Palm Pilot is a very smart hand-held computer based the on the Motorola 68000 Dragon Ball CPU. A few models are on the market: PalmIII, PalmIIIx, PalmV and PalmVII. (The older machines are Palm-1000, Palm-5000, Palm-personal and Palm-professional). All of the new models use the PalmOS-3.x as their operating system. The basic functionality of these machines is the same. The differences between the new models are mainly the RAM size, the screen type, the battery and the shape of the machine. Details about the Palm devices can be obtained from http://www.palm.com/.

The Palm Pilot operating system uses the RAM to store and organize its “files”. Each file on the RAM is actually a Palm Pilot database. Each database has a header indicating the type and the creatorID of the database. The type can be anything: it is a 4-byte value the programmer can assign to his application or data. A type of appl is actually an application. If we assign a different type of database to an application, we will not be able to see it when we press the application button on the Palm Pilot. The creatorID is another 4-byte value; the PalmOS uses this value to identify the database (like a name for a file). The combination of type and creatorID is unique, so we need to apply for a creatorID if we want to give our application to other people. Databases can store resources such as bitmaps, executable code, forms and more. An application, for example, stores its User Interface objects and its code.

To program the Palm Pilot, we first choose a programming language. Many tools and compilers can be run on our Linux desktop to program our Palm Pilot. Here, we use the gcc ANSI C cross-compiler to demonstrate a simple program. Palm provides its SDK (software development kit) and documentation for free, and it is downloadable from http://www.palm.com/. A handy book to have would be the MC68328 Dragon Ball manual from Motorola (for more information, see the Palm web site).

The most important tool we need to install is the gcc cross compiler. The good news about this compiler is that by the time you read this, it should be supported by Palm itself. You should be able to find the gcc, binutils, gdb and prc-tools somewhere at the http://www.palm.com/devzone/ web site. No version of gcc comes with palmOS support out of the box yet; there are some patches to install. The patches come with the prc-tools package, containing the tools needed to combine all resources into a prc (PalmPilot resource database) file. I recommend using the gcc-2.95.2 version and not the earlier 2.7.2, because it fixes many problems. The binutils-2.9.1 should also be patched, as well as gdb-4.18, if you want to be able to debug your application. There is a good chance that by the time this is printed, this group of software will be in one big compressed tar file. The installation instructions for the cross compiler are very simple and may be found on J. Marshall's web page at http://homepages.enterprise.net/jmarshall/palmos/. (This page is about to move to the official Palm site, somewhere under the devzone section.)

Palm Pilot applications use FORMS to interact with the user. These forms contain bitmaps, buttons, tables, check-boxes and many other user-interface objects. A great tool to build these forms for the Palm Pilot, called pilrc, was written by Wes Cherry. The current version (2.4) can be downloaded from http://www.scumby.com/scumbysoft/pilot/pilrc/. It comes as source code and has very good HTML documentation. Listing 1 is an example of a simple pilrc file which builds a simple form, alert, menu and help string. (Please note that the Bitmap with ID 10 was created directly as a resource; there is no reference to it in this file except the ID.)

The command

pilrc /usr/local/example/hw.rcp

will build the two UI objects in this file: the form and the string. Each of these objects will be in a separate file. We will combine these files with the actual code into a prc file (application database) later, using the build-prc command that comes with the prc-tools package. To view the form without actually writing the application, we can use the pilrcui tool. This tool is bundled with the pilrc package. For more information on the UI objects and the use of pilrc, you should look at the Palm official documentation and the pilrc HTML documentation.

The PalmOS keeps a queue of events being handled by the system. These events are sent to the current application in order to execute the code to handle each event. An event is triggered when a UI button is pressed, the Palm pen touches the screen (penDownEvent) or when other operations occur. An application should transfer any events it doesn't handle to the system. When the event is handled, the PalmOS takes the next event in the queue and passes it on to the application. The application can also put events in the queue. Many PalmPilot functions cause all sorts of events to be placed in the event queue. A list of all events and what they do is in the official documentation for the Palm Pilot.

The main procedure of a program is called PilotMain. When the PalmOS calls PilotMain, it transfers a command to it. The PilotMain procedure should find out what the command says. The command can say, for example, that this is a normal launch of the application (sysAppLaunchCmdNormalLaunch) or that this is a command to find a string (sysAppLaunchCmdfind). PilotMain should ignore or respond to these commands in its code. An example of an application that responds to the sysAppLaunchCmdfind is the address book. Whenever we press the find button, the PalmOS sends this command to all the applications. One application that will accept this command is the address book—it starts searching for the string we entered in its database.

To handle all events, we should use an event loop. An event loop simply takes an event, handles it, then takes the next event in the queue. If we do not want to handle a certain event, we can send it to the PalmOS event handlers so it will be handled for us.

To take advantage of all the functionality of the PalmOS, there is well-documented API for your use. You should read the API manual to see which kinds of events, functions and types of objects exist in the PalmOS. Listing 2 is simple code that writes “Hello World” on the Palm Pilot.

The first step toward running an application on the Palm is to build the resources. As mentioned earlier, we can build the resources using the command pilrc.

pilrc hw.rcp

To add the bitmap with ID 10 to the main form, I used a tool that converts ppm files to Tbmpxxx.bin resources. I used xv to convert the format of peng.gif (found at http://www.linux.org.il/) to black-and-white ppm format. Then I used ppmtoTbmp on the peng.ppm file, and named the result Tbmp000a.bin. The 000a in the file name is the 32-bit hexadecimal value for 10. I needed to specify this value because this is the bitmap ID I wrote in the pilrc resource file for the main form. This tool was written by Ian Goldberg, and it can be found at http://www.pilotgear.com/.

The next step is to compile the C code. To do this, we use the gcc m68-palmos-coff cross compiler, with the same flags as for the normal Linux gcc:

m68k-palmos-gcc -O2 -o hello hello.c

The result of this command is an m68k COFF object file named hello. The m68k COFF object file should be combined with the resources just created using the pilrc program. To complete this mission, we first use the obj-res utility that splits the COFF file into the code and data resources, and then use the build-prc utility to combine resources.

m68k-palmos-obj-res helloThis command will split the hello file into three resource files: code0000.hello.grc, code0001.hello.grc and data0000.hello.grc. Now we are ready for the final step of building the prc database.

build-prc hello.prc "hello" hwld *.grc *.binThis command builds a prc application with a creatorID hwld and type appl.

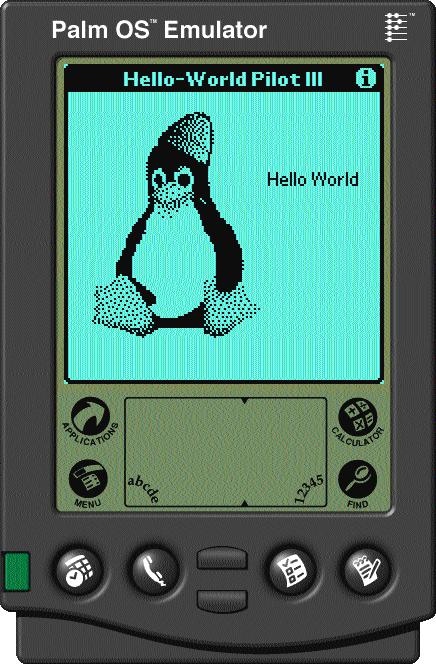

Testing the application on your Palm Pilot is not such a good idea. A bug might require us to reset the machine, and programs can't be debugged with the normal tools. The best way to test our just-created “Hello World” application is with a program that will emulate the Palm Pilot from within our desktop. POSE, available from http://www.palm.com/ with source code included, is a very good emulator. It can use a special debug ROM, also available from that site. With the debug ROM, we can get more debugging information on our application, which makes finding errors much easier, and we can hook gdb to it in order to debug with this well-known debugging tool. To install POSE, you will need the FLTK X toolkit. All instructions come with the POSE tar file.

There is one more emulator for X, called xcopilot. In order to use your own machine RAM or ROM, you can use the pilot-link package. The pilot-link package gives you the ability to communicate with the Palm Pilot from the serial port. There are some good utilities in this package, available from ftp://ryeham.ee.ryerson.ca/pub/PalmOS/. Using the pilot-link utilities, we can also transfer databases from our desktop to the Palm Pilot and from the Palm Pilot to the desktop.

Figure 1

Figure 1 is how POSE looks with our hello world application for the Palm.

Eddie Harari (eddie@sela.co.il) works for Sela Systems & Education in Israel as a senior manager and is involved in some security projects. He has been hacking computers for 13 years.

All listings referred to in this article are available by anonymous download in the file ftp.linuxjournal.com/pub/lj/listings/issue73/3782.tgz.