Put your knowledge to good use by helping develop innovative, fun and educational exhibits for a whole new audience.

Over the past several years, my son and I have spent a significant amount of volunteer time creating exhibit software for the Sciencenter in Ithaca, New York. This article discusses how this project is similar to other software development projects, how it is different and how using Linux has been beneficial. It's not only about Linux or software; it's also about the processes involved, and what you may encounter if you have the opportunity to work in this type of environment.

Science museum exhibit software must be designed with a different audience from the typical computer program, as the software generally is used in a different manner. My earlier Microsoft Windows-based exhibits—Measurement Factory and Fabulous Features—were designed for children up to approximately sixth grade, while the Linux-based exhibits—Sound Studio and Traffic Jam—were designed for fifth to eighth graders. The software must be simple enough that the target audience understands a significant amount of what they see on the screen and how it relates to the exhibit. A computer in an exhibit is not necessarily the exhibit; it may act as a guide or simply be another “manipulative” along with real-world objects.

A second “audience” also must be considered, the museum staff. Floor personnel (many of whom are volunteers) shouldn't have to be trained in the vagaries of each computer. Exhibit software and hardware also should come up and run automatically when the systems are powered on first thing in the morning, as museums tend to turn off at least some circuit breakers when they close in the evening. Trust me, you want the museum staff to like your exhibit—if it makes their life difficult, the exhibit may sit there with a sign saying “broken”.

Possibly the most important thing to keep in mind when you're developing your dream exhibit is this: when you build a non-hidden computer into a museum exhibit aimed at younger visitors, you're competing with every video game they've played and every television show or movie they've watched. Your exhibit, therefore, must be extremely cool.

Measurement Factory is cool because visitors can weigh themselves, measure their height, test their grip strength, compare themselves to others of their age and get a certificate when they're done.

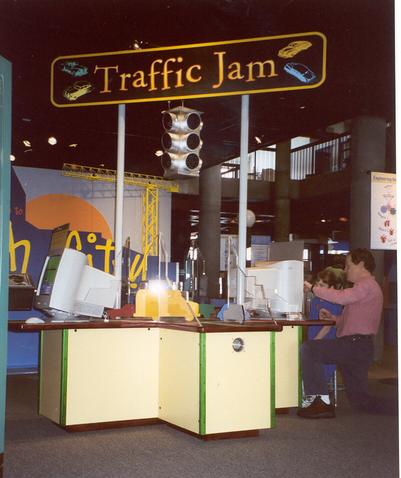

Traffic Jam (Figures 1-3) is cool because visitors can play with traffic lights and prevent traffic jams—or not, if they prefer.

Figure 1.

Sound Studio (Figures 4-6) lets visitors record themselves and their friends on a multitrack recorder and play with simple special effects, such as echoes.

Cool has a definite limit, however. For instance, it's not a good idea to make the “you made a mistake” annunciator—sound, animation, whatever—too cool; otherwise visitors will consider that the goal. Don't defeat the purpose of the exhibit.

An orderly development process is important here because of the educational goals and target audience. Some of the following actually may be quite informal, but it is important nonetheless. Your development cycle may not be exactly like this, of course.

The kickoff meeting: if you're building a standalone exhibit that is not part of a coordinated exhibition, this may not happen. Tech City, however, was to consist of around a dozen coordinated exhibits, with a central theme of engineering. Therefore, an all-day kick-off meeting was held to discuss project goals and to arrive at an initial focus. I've attended several meetings of this type, and all were well worth the time. In addition to getting a feel for the project, you'll pick up a few good ideas and meet people who may be helpful later on in the process.

Brainstorming: put your feet up and don't even worry about Linux until you come up with a few good ideas. On the other hand, if you know of a good existing application that could be modified and made useful, mention it and make note. While kicking around your cool ideas, keep handy a list of the project requirements. These can range from something quite simple, such as “demonstrate a type of engineering”, to something more difficult, like “demonstrate Heisenberg's Uncertainty Principle for elementary schoolchildren in a nonstructured, graphical manner using virtual manipulatives.” Always keep the requirements in mind, but I can guarantee that they'll change right up to the day you ship.

Prototype construction: this phase is the same as building prototypes anywhere else, but it can be even more fun because of the people you're working with. The museum people we've worked with over the years have been intelligent, creative and enthusiastic about their jobs. Don't be too shocked by the appearance of the kiosk prototype if your exhibit requires one. There's probably going to be a lot of duct tape and cardboard involved.

First review: this is where you show off your prototype for the first time, for critiquing. Don't worry if the adults involved in the process don't think your exhibit is as cool as you know it is. Remember, most adults don't think like kids. Show your prototype to a few kids in the target age range, informally.

Target test: this might be the most fun part of building your exhibit. It's the first, and possibly second and third, time that it's set up for museum visitors to try, so you and possibly other people can observe the results. Expect to go through this process several times. Important questions to consider include: Is the exhibit inviting to visitors? How long do visitors stay at the exhibit? Do several visitors use it together? Do visitors learn what you're trying to teach? Do visitors use the exhibit the way you intended? Can visitors figure out how to use the exhibit successfully? Does it appeal to the correct age bracket?

You may be able to interview visitors after they've tried your exhibit, or museum personnel may do so and report their results to you. This is probably the most valuable information you'll receive; kids can be brutally honest.

Professional evaluation: there are firms with expertise in evaluating educational programs such as museum exhibits. If your exhibit is being built as part of a National Science Foundation (NSF) grant, it likely will be evaluated by one of them. We've only had the opportunity to deal with one of these firms, Inverness Research Associates, but found their comments to be extremely helpful. If you have the chance, observe them at work—you'll learn a lot.

Revision, including code cleanup: like the prototype construction step, this is similar to what it would be like anywhere else. It's well worth taking the time to add extra comments and clean up any kludged code. Museum software tends to accumulate extra bits and pieces. If you need to modify your software sometime in the future, the extra time spent now may more than pay for itself later. At this stage, the nice versions of the non-computer parts of your exhibit are probably being built as well.

Deployment: again, this isn't much different from anywhere else, though you'll want to keep the turnkey and no-maintenance requirements of this sort of project in mind. If your software is shipping as part of a larger exhibition, remember that museum personnel will be extremely busy at this point, so make things as easy as possible for them. System deployment for Tech City ultimately consisted of setting up the systems—four targets, plus a spare—installing Linux on each and testing with the CD-ROMs we'd already prepared (see the Tips and Tricks section below).

Your software may have to run on an old PC that has been sitting around unused or on a latest-generation machine that has been donated specifically for the project. Or, if you're lucky—from the Linux driver perspective at least—you'll get a machine that is one generation old.

If you're able to specify the deliverable hardware, be conservative; try to look at this from the turnkey system viewpoint, as opposed to office desktop. Well-debugged hardware and drivers are probably going to be worth more to you than the latest-and-greatest devices, and saving a few degrees of cabinet temperature by using a somewhat slower processor and video board might prevent a failure six months from now in a faraway museum on a warm summer day. Don't be stingy with system cooling. If you can, specify good-quality fans, and make sure that whoever builds the exhibit kiosk, if there is one, provides for adequate airflow to and from the computer.

The Tech City software was deployed on donated Hewlett-Packard Vectra 400s, each with a 1GHz PIII processor, an i810 chipset with onboard video and a 20GB HD. We also added an Sound Blaster 16 PCI card to each machine, as Sound Studio requires either a full-duplex sound card or two cards without that capability. Each system was supplied with a 19" monitor, also donated by Hewlett-Packard.

Not knowing anything about your project, I can't recommend specific tools and libraries. I won't even try to recommend implementation languages to you. I can, however, suggest a few guidelines that worked for us.

Experienced developers probably have heard this already, but if an existing package is close to what you need to accomplish a particular task, think about modifying and using it. The Traffic Jam user interface is split across four windows—traffic display, density setting, control and other information. We used GTK+ because of its extensive theme capabilities and the icewm window manager for the same reason. We did, however, need to modify the latter slightly.

Carefully read the licenses for the code you want to borrow, of course. Respect the author's wishes, and don't create any liabilities for the museum. As with hardware selection, being conservative is good. If you really don't need the features available in the latest version of a tool or library, don't rush to install it—known bugs are easier to work around than unknown ones. Don't forget about maintenance and project lifetime; either you or someone else may have to modify this project in the future. A nonrelease version of a language or library might seem wonderful and stable now, but two years from now it might be quite different and somewhat incompatible. Even g++ changed in the four years from when I wrote the prototype Linux version of Traffic Jam until the final software was delivered.

Lastly, I'll go out on a limb by suggesting that you also be conservative with regard to selecting a Linux distribution. Latest and greatest may be ideal for your desktop, but again, reliability is far more important in the field. We chose Debian 3.0r0 for our final system deployment soon after it was released, but because Debian has a reputation as a conservative distribution, we felt comfortable with that decision.

Here are several of the problems we encountered and how we solved them. The solutions may not be optimal, but they worked well for us.

Problem: How did we set the systems up as turnkey? They must power into the exhibit software automatically; no user intervention required. Museum staff also must be able to update software easily, as required.

Solution: We solved this by mounting the CD-ROM application directory over (on top of) the exhibit home directory, /home/techcity for example, and automatically logging on as that user at startup. If the appropriate CD-ROM isn't present—each deployment CD contains the software for only one exhibit—the console displays a message asking the user to put it in and then reboot. (Although not accessible to visitors, a keyboard is in the cabinet with each computer.) The reboot monitor watches a FIFO for either an R to reboot the system or a Q to quit, though we also considered using it in other ways. See Listing 1 for pseudo-code describing this process, Listing 2 for our autostart file and Listing 3 for a sample .xinitrc.

Listing 1. Pseudo-Code for Turnkey Application Startup

Listing 2. File 599xx-mytechcity, Inserted into /etc/rc2.d to Sequence Exhibit Software Startup

Problem: This type of application generally needs fine-tuning. How did we accomplish this?

Listing 3. Sound Studio Application .xinitrc File

Solution: Our first idea was to use a configuration file format based on the Windows .ini file. This would have worked for Sound Studio but not for Traffic Jam. The latter required, among other things, the defining of multiple vehicle types, which made XML's ability to represent easily multiple instances of the same class useful. My son coded a C library designed to run on top of xmllib2, which allows our software to access the various elements as a tree—based on the path to that element within the document, in other words.

Listing 4 shows a section of the DTD for the Traffic Jam configuration file, and Listing 5 contains the associated section of the file. Listing 6 is a section of the code used to load vehicle physics—notice how Cfg points to a C++ object wrapped around the library functions mentioned previously.

Listing 4. The Vehicle-Definition Section of the DTD for the Traffic Jam Configuration File

Listing 5. The Vehicle-Definition Section of the Traffic Jam Configuration File

Listing 6. Loading Vehicle Physics Constants from the XML Configuration File

Problem: How to deal with window manager security? Visitors shouldn't be able to exit the software, bring up other applications, move windows around and so on.

Solution: We found that when visitors had access to the keyboard during early testing, they were quite good at finding their way out of the applications. We fixed this with a combination of configuration file and code changes to icewm to disable pop-up menus, window moves and window resizes. Also, neither exhibit requires the use of a keyboard, so that's kept inside the kiosk during normal operation.

Educational software may not be your cup of tea, but if it is, try to find a science museum to help. They like seeing new faces, they can always use the help, and I can promise that you'll get back more than you give.

I'd like to thank the staff and volunteers at the Sciencenter, Ithaca, New York, for running a terrific museum and encouraging people to think outside the box; check out their web site at www.sciencenter.org.