Use one system to manage voice over IP and conventional phone lines, manage voice mail and run CGI-like applications for phone users.

So, you need to deploy a Private Branch eXchange (PBX) system for your small office. Or, maybe you want a voice-mail system running on your Linux box at home. What about an interactive voice response (IVR) system for home automation? Voice over IP (VoIP) capabilities would be nice too. How do you do it? One very interesting and powerful solution is Asterisk, a GPLed PBX system built on Linux that bridges the gap between traditional telephony, such as your telephone line, and VoIP. Asterisk also supports a host of other features that make it an attractive solution. In this article, I touch on some of these features and give you enough information to get started without having to buy any special hardware.

Asterisk is an open-source project sponsored by Digium. The primary maintainer is Mark Spencer, but numerous patches have been contributed from the community. As of this writing, it runs only on Linux for Intel, although there was some success in the past with Linux PPC, and an effort is underway to port Asterisk to *BSD. Digium also sells various hardware components that operate with Asterisk (see Resources). These components are PCI cards that connect standard analog phone lines to your computer. Other hardware is supported as well, such as hardware from Dialogic and Quicknet. Asterisk has its own VoIP protocol, called IAX, but it also supports SIP and H.323. This leads us to one of Asterisk's most powerful features: its ability to connect different technologies within the same feature-rich environment. For example, you could have IAX, SIP, H.323 and a regular telephone line connecting through Asterisk (see Figure 1—courtesy of Digium).

Figure 1. Asterisk can connect regular telephone lines and multiple VoIP standards.

The developer can extend Asterisk by working with the C API or by using AGIs, which are analogous to CGI scripts. AGIs can be written in any language and are executed as an external process. They are the easiest and most flexible way to extend Asterisk's capabilities (see Listing 1).

An official release hasn't happened for quite a while, but there is talk of one coming. Currently, the best way to get Asterisk is by CVS:

export CVSROOT=\ :pserver:anoncvs@cvs.digium.com:/usr/cvsroot cvs login (password is "anoncvs") cvs co asterisk

If you plan on using a PCI card from Digium, you should look at zaptel as well. If you plan on having connectivity, you need to check out libpri.

There is no configure script, so you simply use make. You also need readline, OpenSSL and Linux 2.4.x with the kernel sources installed in order to compile Asterisk properly:

cd asterisk make clean install samples

This compiles Asterisk, installs it and also installs the sample configuration files. The last target overwrites any existing configuration files, so either skip this target or back up any existing configuration files if you want to preserve them. If you are using zaptel or ISDN, compile those before compiling Asterisk. Asterisk is installed in /usr/sbin/ with the configuration files in /etc/asterisk/ by default. Voice-mail messages are stored in /var/spool/asterisk/voicemail/. CDRs for billing and log files are located under /var/log/asterisk/.

You can start Asterisk by typing asterisk at the command line. However, the best way to use Asterisk during the testing phase is to run it with the -vvvc options. The -vvv option is extra-verbose output, and the -c option gives you a console prompt, which allows you to interact with the Asterisk process. For example, you can submit commands to Asterisk, such as management and status commands.

Asterisk's operation and functionality relies on several configuration files. We discuss three of them in this article, but several others exist. Here, we set up Asterisk so that users can call each other through IAX. We also set up voice mail and give users a way to manage their voice-mail messages.

Before getting into the setup of Asterisk, we should have a general understanding of the dialplan. It is flexible and powerful but also can be confusing. The dialplan is used to define number translations and routing and, therefore, is the heart of Asterisk. The dialplan defines contexts, which are containers for extensions (digit patterns) that provide specific functionality. For instance, you may want to provide a context for people who are in your office or home, so that they have certain dialing privileges. You also could set up an external or guest context that allows only limited dialing capabilities, such as no long distance. Context names are enclosed by brackets ([]). The extensions associated with the context follow the name.

Each extension can have several steps (priorities) associated with it. The call flow continues sequentially unless an application returns -1, the call is terminated or the application redirects the call flow. The syntax of an extension entry looks like this:

exten => <exten>,<priority>,<application(args)>

An extension is denoted by using exten =>. In this example, 9911 is the extension; 1 and 2 are the priorities or step numbers (these need to be sequential); and Wait and Dial are the applications. Asterisk uses applications to process each step within an extension. You can get help for the different applications from the Asterisk console by typing show applications to list the supported applications and show application <application> to display the help message.

Extension matching can be done on the dialed number as well as the calling number. This allows for greater flexibility when processing calls. Patterns also can be used, and these are preceded with an underscore (_):

N—a single digit between 2 and 9.

X—a single digit between 0 and 9.

[12-4]—any digit within the brackets.

. —wild card.

For example, the extension _NXX5551212 would match any information number, regardless of area code.

Extensions can be any alphanumeric string. Some special characters are built-in:

s—start here when no dialed digits are received, as from an incoming call from an analog line.

t—used when a timeout occurs.

i—used for invalid dialed digits.

o—operator extension.

h—hangup extension.

The first file we create is the iax.conf file (see Listing 2). This file controls the operation of the IAX protocol and defines users of the protocol. The protocol has two versions. The old one is IAX, and the new one is IAX2.

The first section of the configuration file is the general section, which defines parameters for the IAX protocol. Four parameters are listed, but others can be defined as well. The port parameter is the port number over which IAX will communicate. It defaults to 5036, so strictly speaking, that entry is not needed. You can use the bindaddr parameter to tell Asterisk to bind to a particular IP address—for machines with multiple Ethernet cards. A bindaddr of 0.0.0.0 attempts to bind to all IP addresses. The parameters amaflags and accountcode are used for CDRs. When they are defined in the general section, they are used as the default values. You also can define them on a per-user basis. The values that amaflags can accept are billing, documentation, omit and default. accountcode can be an arbitrary value. For this setup, I use home for users local to my LAN and external for users outside of my LAN. Several other parameters have been omitted, but most of them are performance parameters.

The remaining sections are user definitions. I have three users: brett, maria and niko. The type definition has three possible values: a peer can receive calls, a user can place calls and a friend can do both. I have defined all of them as type friend. I defined all of the hosts as being dynamic, but if any host has a static IP address, you can specify that instead. secret is the password the user must provide when connecting to this Asterisk server. Two contexts are used in this file for users: [cg1] and [cg2]. I explain these in more detail when discussing the extensions.conf file, but effectively, these contexts enable the dialing privileges for the user.

The next file is voicemail.conf (Listing 3). Again, it has a general section that deals with general or global parameters for voice mail. The first parameter, format, lists the audio format of the messages. The next two parameters are used for e-mail notification: serveremail is the source e-mail address (from field), and attach instructs Asterisk to attach the message to the e-mail. In our example, we do not want the message attached. Again, some parameters have been omitted.

<mbox> is the number used to save and access messages for the user. This is also used in extensions.conf for directing the call flow to the proper voice-mail box. The <passwd> parameter is needed when checking messages. <name> is the name of the user. <email> and <pager> are e-mail addresses that are used to send message notifications. The pager e-mail has a shorter message, because it needs to be read on smaller devices (pagers and cell phones). Many mobile and pager providers have e-mail gateways that can deliver the message to the device.

The last file that we examine here is the extensions.conf file (Listing 4). This is one of the most involved files because it contains the dialplan. The dialplan in my example is rather simple compared to its capabilities. This file has a general and global section. The general section is similar to the general section in the previous files; it defines general parameters. I don't define any general parameters in this example. The global section is used to define global variables. These variables can be accessed in the dialplan by using the syntax ${VARIABLE}. I have defined one variable: TIMEOUT is the answer timeout. Built-in variables also can be used within the dialplan, such as, CONTEXT, EXTEN and CALLERID.

All of the other sections are context definitions. A context is simply a grouping of digit patterns. Here I have defined several contexts that define dialing scenarios: voicemail, iax and afterhours. Think of these as individual or mini-dialplans. I then define two contexts that I assign to the users. These inherit the capabilities of the other contexts I already have defined by using the include keyword.

The first context, voicemail, lists the digit patterns that allow users to access their voice-mail messages. Users can dial 6245, and the application VoicemailMain2 prompts them for the mailbox number and password. Users then can manage (listen to, delete and so on) the messages in their mailbox.

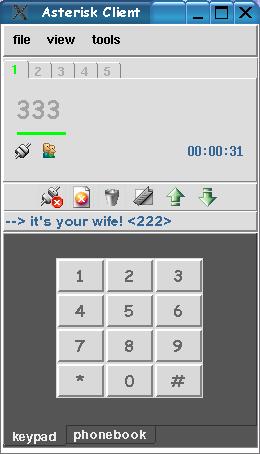

The iax context is used for PBX dialing between IAX users. We have defined various extensions for each of the users. An entry with the name of the user (maria) redirects to the extension number entry. For the 111 extension, I also match on callerid. If the callerid matches, I change the callerid name so it has a relative meaning. For example, if the extension dialed is 111, and the callerid is 222, the callerid name is changed to “it's your wife!”. This message shows up on my client whenever my wife calls me (I won't get into how I use this to my advantage).

The last digit pattern context is used for calls that arrive during late hours. Because I don't want to be disturbed at night by external users, I match on any dialed number (_.). It waits for one second and then answers the call. After it answers, it plays a background message so the caller can choose for which person to leave a message (“for brett, press 1”). So, if the caller presses 1, the call proceeds to the 1,1,Voicemail2(111) entry, which sends the user to the 111 mailbox. This is a simple illustration of how you could construct an IVR system.

The [cg1] and [cg2] contexts include functionality I already have defined inside other contexts. This allows me to create different user groups easily. For example, [cg1] has all of the capabilities I have defined, but [cg2] has only the iax capabilities and gets directed to voice mail during late hours. Powerful dialing capabilities can be constructed by utilizing the flexibility of Asterisk's dialplan. My example has shown only a glimpse of the possibilities. You also can simplify the dialplan by using macros, but I leave that as an exercise for the reader.

In the extensions.conf file, an entry called callerid.agi calls an AGI script. This is a simple example illustrating the AGI interface. The script is placed in the /var/lib/ asterisk/agi-bin/ directory and is invoked by Asterisk as an external process. AGI and Asterisk communicate through stdin, stdout and stderr. Variables are passed in to the AGI through stdin, and the AGI can pass information back to Asterisk through stdout. Messages destined for the Asterisk console are written to stderr. Two parameters always are passed to the AGI: the full path to the AGI and the arguments that are passed to the AGI through the exten entry. The AGI collects the callerid and sends it to a GUI application running on another machine. The GUI application can be retrieved from my Web site (see Figure 2). AGI scripts also can be used to retrieve information. If you need to query a database for information about the call or the user, you can use the AGI interface as well.

So, what can we do now? After creating the configuration files above and starting Asterisk (asterisk -vvvc), we can try some calls. Currently, the availability of IAX soft clients is limited. SIP soft clients, including kphone and xten, and hard clients from Cisco, SNOM and other vendors also are available that will work with Asterisk, but I concentrate on using IAX in this article. Gnophone (Figure 3) is the oldest client and was developed by Digium. Work also is being done on a cross-platform client, as well as a Windows client. Another client is available that belongs to the tel Project at SourceForge. I have modified the user interface to that client (Figure 4). It is still alpha software, but it's functional. In fact, I used this client to establish a call between Germany (Reinhard Max), Australia (Steve Landers) and the US (me). Whichever client you choose, you need to define your user name, password and context for each Asterisk server with which you want to connect. Then, you can call anyone defined in the iax.conf file (if the dialplan is set up correctly). So, if I want to call my wife, I simply dial 222, or I can type maria (because I have defined this in the dialplan). If I want to check my voice-mail messages, I can dial 6245.

Figure 4. Alpha but working software: a modified version of the client from the tel Project.

I have touched on only a few of Asterisk's capabilities, but this article should give the reader a glimpse of Asterisk's potential. Asterisk scales well from small setups to larger and more complex configurations. For example, Asterisk servers in different locations can be connected through the IAX protocol, creating a virtual PBX. Because Asterisk runs on Linux you can leverage existing tools to help interface and manage Asterisk. For instance, you could have Web access to the CDRs, configuration files and voice mail. In fact, a CGI script comes with Asterisk that allows you to access your voice-mail messages with a Web browser. I encourage readers to explore Asterisk further and leverage its powerful features.

I would like to thank Digium, Reinhard Max and Steve Landers for their assistance with this article.