Give your command-line tasks a GUI with the Mozilla platform.

One of the more powerful features of Linux is the simple way that new commands can be constructed using aliases, shell scripts and other textual tricks. These techniques rely on a command-line interface, but what if you need a tool with a GUI interface? Few techniques exist that are both easy to use and professional looking. This article discusses a promising technique that uses the Mozilla platform. It focuses on a rather hard but standard problem: how to display the hierarchical information delivered by the ps(1) command usefully. A recent version of Mozilla (at least 1.4) is required.

Numerous GUI toolkits are available for Linux, from Xt to Tcl/Tk. Tutorials for these kits usually start with a button example. That's very routine, so let's see it and move on. In Mozilla, GUIs are described using XML syntax. A document named button.xul that specifies a button looks like this:

<?xml version="1.0"?> <window xmlns="http://www.mozilla.org/keymaster/ ↪gatekeeper/there.is.only.xul"> <button label="Press Me"/> </window>

The unmanageably long string, http://www.mozilla.org/keymaster/gatekeeper/etc..., tells Mozilla this file isn't HTML. It's instead XUL, a GUI description language that is Mozilla-specific and a dialect of XML. Make the button's window appear with this command:

mozilla -chrome button.xul

This example is simple and not worth dwelling on, although there's a lot going on even for a simple button. A ps(1) display is a far more ambitious goal, so let's leap forward.

Instead of the simple <button> widget, one of Mozilla and XUL's bigger guns is required, the <tree> widget. Some coding also is required and a lot more XML. Here, the focus is on fast development, not on seamless perfection. The coding part comes first.

To begin, ps(1) does the initial data gathering. Listing 1 shows the file psdata.ksh, with mode 777.

The output holds all the interesting fields, comma-separated with no header line. Mandatory components are PID and PPID; the rest are optional but informative fields, such as COMMAND. That's all traditional Linux requires.

The rest of the coding depends on Mozilla technology. The standard compiled distributions provide at least two executables, mozilla and regxpcom. Here, a binary named xpcshell is used as well. This binary is Mozilla's JavaScript equivalent of the Perl interpreter; it has no GUI support. xpcshell sometimes is a good starting point for development, but it is never essential. To acquire this binary, a full compilation of Mozilla is required. First, check toolchain requirements against www.mozilla.org/build. Next, grab the source by FTP or remote CVS. A major release rather than a nightly release is recommended. Once unpacked, follow standard compilation steps:

cd mozilla ./configure --disable-debug make make install

Debug versions are slow and have messy diagnostics; although harmless, they're avoided here. The build takes an hour-plus to finish and requires up to 1GB of space. The resulting binaries are located in mozilla/dist/bin. They can be run from that directory or from anywhere if the MOZILLA_FIVE_HOME and LD_LIBRARY_PATH environment variables are set and exported to that directory's absolute path. Now all the required binaries and shell scripts are available.

With Perl, the output of ps(1) needs to be sucked up into a coding environment. In this case, that's a JavaScript interpreter. To do this, you need more than language syntax—you need support for I/O. In Perl, support is built into core language functions. By comparison, JavaScript has no I/O functions. In Mozilla, that I/O support is added using objects. Such objects cannot come from a scripting library, because the core language has no I/O. So, a Perl use or require doesn't work. There are no back-tick operations either, such as echo `pwd`. Instead, Mozilla has XPCOM.

XPCOM is an implementation of Microsoft's COM, and it works portably on Linux/UNIX, Windows and Macintosh. It's restricted to a single process at the moment; there's no DCOM. XPCOM/COM is the fastest way to add new functionality to a scripting environment. It hooks up a compiled (say C or C++) object to an object reference in the scripting language. The nearest Perl equivalent is XM, but XPCOM does not require the re-linking that XM demands. Mozilla includes thousands of XPCOM objects by default. XPCOM is not some Java-like virtual machine at work, however. XPCOM objects usually are compiled code that runs efficiently on the bare metal.

It might seem strange to use Microsoft ideas on Linux, but XPCOM is fully open source and occupies a UNIX niche that has long been unaddressed: Linux/UNIX lacks a useful intermediate-sized component model. There have been CORBA and dynamic link libraries in the past, but those things are, respectively, very heavyweight and very lightweight. XPCOM is suited perfectly to middle-sized jobs, to application development of large binaries and to performance-critical work. Here it's simply extremely handy.

Use of XPCOM or COM typically includes many calls to the Windows QueryInterface() method. For the sake of Linux programmer sensibilities, this article uses createInstance() and getService() instead. QueryInterface() is available too.

Back to the code. Let's suck up the output of the ps(1) wrapper. Listing 2 shows how.

The first part of this listing sets up some globals. The Components object is a pre-existing object that acts as a directory of all existing XPCOM objects, called components, and their supported interfaces (in the Java or COM sense). To get an XPCOM object, find the right component (named with a string called a Contract ID) and construct an interface object for it (also named by a string or by a property name; the latter is used here). It's common to reuse components, so once found, they're saved as handy property values on the klass object—class is a reserved word in JavaScript.

Two defined functions are run at the end of this listing. execute_ps() simply executes another process: the ps(1) wrapper script. For that it needs a file object (an nsILocalFile) and a process object (an nsIProcess). run() invokes the process using fork(). Mozilla is designed to do all this portably, but here only Linux is supported because the path of the executable is hard coded as a constant. The other function, read_raw_data(), sucks up the data. Mozilla uses stream, transport and channel concepts the same as do some high-level features of Java, but without the complexity of having to write any classes. A file object is needed for the data file dumped by ps(1). A stream object opens a content pathway to that file. A minor hack is required as well: a special scriptable stream object must wrap the basic stream. With one read() call the whole file is slurped up into a string. Next, some Perl-like regular expression wizardry breaks the content down into an array of lines and then further into an array of arrays. All data is treated as string data. To see if the data is processed correctly, try using the diagnostic and rudimentary print() method supplied with xpcshell. Alas, Mozilla currently does not support retrieving PIDs, so files named /tmp/psdata.$$ don't work yet. That support is nearly here, though.

Many XPCOM objects are in this script, so how are you to find the right ones? As with any programming library, there's reference material. Look for .IDL files in the Mozilla source code (or under mozilla/dist/idl), on the Web or read a book.

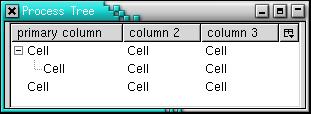

That's enough scripting to start with; scripting and tabular data are well understood in Linux. To build the GUI, Mozilla requires XML, specifically, XUL. That's a different world from the command line, and you have to be familiar with XUL to succeed. Here, the process is broken down into easy stages. First, Listing 3 and Figure 1 show an XUL <tree> widget.

Figure 1. Simple <tree> Widget with Static XUL Content

The tree looks nice because the <?xml-stylesheet?> processing instruction drags in the current Mozilla theme for free. Display this tree with the normal Mozilla executable, using the -chrome option to rip away the normal navigation buttons and other decorations:

mozilla -chrome static_tree.xul

The XML content (henceforth, the code) is a bit like an HTML <table> tag: both column headers and rows of data are specified. The <treeitem> tag is the tricky part; it can contain a <treechildren> tag, which allows the tree to have subtrees, rather than only depth 1 leaf nodes. As seen in Figure 1, the tree widget has a number of interactive features; subtrees can be opened and closed in the same manner as any file explorer application, including Nautilus or Windows Explorer. Columns can be added or deleted using the column picker, the small icon at the extreme right of the tree header that holds column names.

If we wanted, JavaScript scripts could be used to insert the ps(1) data into this XUL document dynamically. That's not hard, and all of the W3C's DOM interfaces are available to do the job. Start by adding Element objects or even use the .innerHTML property. This is an ambitious article, so instead you see a fully data-driven approach, one that avoids hand-constructing any tree.

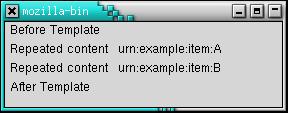

Listing 4 and Figure 2 show an XUL GUI without a tree. This one has a <template> tag instead

Figure 2. Simple Templated GUI Based on Static RDF Content

An XUL template is like a report template and not like a C++ template. It's the basis for repeated sets of data. The template starts with the <vbox> tag that has a datasources= attribute. The <action> part of the <template> is the content to be repeated for every record that the <conditions> part identifies in the trivial.rdf file. If you're an intermediate at make(1) or SQL or have touched Lisp, Scheme or Prolog, you should be able to grasp how the template system works. Listing 5 shows the trivial.rdf file that drives the display of Figure 2.

If this file is modified, Figure 2 can change even though Listing 4 hasn't been altered. That's a data-driven arrangement. This file is RDF, one of the harder W3C standards. Basically, it's a graph of nodes, each node holding three items of data. The items are called subject, predicate (or property) and object. Simple graphs are trees, so Listing 5 is a tree. Combine the <hbox> in Listing 4 with the <li> tags in Listing 5, and the result appears as illustrated in Figure 2. This is somewhat like an SQL join or join(1). For now, notice that the ref= attribute in Listing 4 matches the <Seq> tag in Listing 5. This is how the two are matched up in Mozilla's template processing logic. Mozilla support for RDF is basic rather than strict, so nearly all the URIs and URLs can be made up on the spot, as though they were variables or constants. That's done throughout this article. Try adding another <li> tag to Listing 5; restart Mozilla and display the page again.

A tree is a good way to display a hierarchical list of processes, and a <template> is a good way to drive the appearance of a tree direct from data. No RDF document is available to work with, though; instead, we have a JavaScript array of records. The solution is to put a <tree> and a <template> tag together and set the RDF file to rdf:null = no file. A script is used to create the RDF content directly from JavaScript data. Because of RDF's peculiar design, the content can be dumped into the template in a careless manner and everything simply works. That's a far cleaner but admittedly a more subtle solution than hand-building an XUL tree from JavaScript. Another clean aspect of RDF and templates is the tree can be updated anytime in a simple manner. This means the window can display ps(1) data dynamically, as though a GUI version of watch ps H were run. That dynamic step is beyond this article's scope, however.

If the <tree> and <template> tags are put together, the final XUL document is as shown in Figure 3 and Listing 6.

Again, you can spot the datasource= and ref= attributes and the <template> tag. The URLs beginning with rdf: indicate spots where RDF data should be put into the template. In the earlier example, variables started with a question mark. Two syntaxes are available to mark such spots. Not surprisingly, there's one such piece of data for every column and every row.

The <splitter> tag is simply friendly decoration; it allows the user to resize the columns. Doing so aids readability, as do the minwidth= and flex= attributes. Figure 3 shows how the displayed process hierarchy naturally fills the tree.

Near the top of Listing 6, a <script> tag includes all the code from Listing 2, plus more. When such scripts are included, there is an immediate security problem. The problem is Mozilla technology must ensure secure display of remotely located files and scripts, such as HTML pages. This is like the Java Server of Origin rule. xpcshell is entirely unsecured, but the main Mozilla binary has normal security. With an intensive configuration effort, security restrictions can be overcome, but it's simpler to register the script as a package. To do that, all the files have to be moved to the chrome, a directory inside the Mozilla install area where all security restrictions are lifted. How to do that is explained shortly, but first we finish the application with a script that moves the ps(1) data from a plain JavaScript data structure into an RDF datasource. This script replaces the static RDF file used earlier (Listing 7).

Listing 7 shows the extra script logic that substitutes for a static RDF file. Adding the JavaScript data to the RDF used by the tree's template requires a process of steps. Mozilla sucks up RDF data into an object called a datasource. Because rdf:null has been specified, no datasource object exists, so one must be created and attached to the template. load_handler() does that, after the document is loaded safely. Using an onload handler is a standard HTML trick, and such tricks apply equally well to XUL. The update_tree() function then fills that datasource with RDF content for the template. It's done pretty simply. A double loop steps through each data item in the JavaScript array. For each ps(1) process, Assert() is called to create one RDF node of data (a triple of three items) that states PPID X has child PID Y and a further set of RDF nodes that states PID X has USER A or PID X has GROUP B. The <template> and the <tree> tag work together to sort those RDF nodes automatically into a tree arrangement; this is like make(1) calculating the dependency tree for all the targets stated in a given Makefile. With this script acting in place of a static RDF file, the simple process viewer is complete. Finally, the steps required to lift security by registering the code as a package are:

M5H = $MOZILLA_FIVE_HOME mkdir -p $M5H/chrome/psviewer/content cp * $M5H/chrome/psviewer/content vi $M5H/chrome/psviewer/content/contents.rdf vi $M5H/chrome/installed-chrome.txt

The first vi editing session creates the file contents.rdf. It must look exactly like Listing 8. The second vi editing session adds to the file installed-chrome.txt. A single line is added:

content,install,url,resource:/chrome/psviewer/content/

When Mozilla starts up, it examines this last file. If it is modified, the directories listed are examined for contents.rdf files. Those files are then read, and like make(1), Mozilla builds in its head a picture of all the packages known to exist. All known packages have full security access, and Listing 8 adds the package psviewer. The secure files now can be displayed and run with a URL such as:

mozilla -chrome chrome://psviewer/content/tree.xul

instead of:

mozilla -chrome file:///home/nrm/psviewer/tree.xul

The psviewer tool has first-class status within the Mozilla installation. If necessary, it could be integrated with other applications, such as the Firefox/Firebird browser or Thunderbird e-mail client. It also could be added as a menu option to the Tools menu, for example.

There's a lot of technology in this article. The biggest mistake you can make is to try to use all the features described here in your first Mozilla experiment. Because validation of XML is less than verbose in Mozilla, you easily can become tied in a knot. It's best to start with a simple project and work up to the challenging combinations played with here. Although the output of ps(1) also can be made into a dynamic HTML page, XUL is a more robust and professional GUI in the end, fully integrated with the desktop.

Mozilla is a powerful GUI environment waiting to be explored. It is likely to occupy the same niche under Linux that Visual Basic occupies under Windows. Even better, Mozilla is a portable and cross-platform technology. Your projects can be designed to work on BSD, HP-UX, SunOS, AIX and Mac OS X, as well as Linux.