Combine Samba with OpenLDAP for a mail and SSH single sign-on system.

Welcome to the third installment of how to implement a single sign-on and corporate directory system. In this article, we tackle integrating Microsoft Windows clients. There's a lot involved to make it all happen, so put on your work gloves and let's get to it.

When you want to integrate Windows clients into a heterogeneous environment, you have some choices to make. Although you can run an Active Directory (AD) server and have your Linux and Apple clients bind to it for authentication and identity management, the costs involved are not minimal. It also wouldn't make for an interesting article on an open-source single sign-on and directory implementation.

When you're binding Windows clients to an open-source solution, you have two more choices to make. Do you bind them to the Kerberos realm for authentication or do you bind them to LDAP for identity management? This is an either/or choice because although Windows clients know how to speak both Kerberos and LDAP, they know how to speak them at the same time only when talking to an AD server. In other words, Windows clients can talk to a non-AD Kerberos server only when the user's identities are kept locally. Likewise, a Windows client can get identities from LDAP via Samba, but only when the passwords are also served via Samba, and Samba can't, at the moment, authenticate via Kerberos.

Having Windows authenticate against our Kerberos KDC is easier to set up, but it could be harder to maintain because every user who uses the Windows client needs to have a local account. This is fine if all you have is one Windows client to maintain, but if you have any more than that, you'll need to add every user to every client. I won't explore this option; however, if you're interested you should pick up Jason Garman's Kerberos: The Definitive Guide.

Because we're dealing with a corporate directory, I'm assuming you probably have more than one Windows machine on your network. In order to make using them and incorporating them as painless as possible, we use Samba tied to our LDAP directory as a back end. Even though we'll be configuring Samba a little differently, you should first read Craig Swanson and Matt Lung's “OpenLDAP Everywhere Revisited” (see the on-line Resources), as it will give you a good foundation on which to build. I created an organizational unit branch in the directory named samba for Samba specific entries such as machines and ID maps. Listing 1 shows the hierarchy of these special branches, and Listing 2 shows the LDIF for them.

I don't use the smbldap scripts from IDEALX for creating necessary entries, because I'm using LDAP for more than just Samba authentication. One main reason for not using the smbldap tool is because it assumes that it and Samba will be the only point for actions such as adding users and groups. In my environment, all users don't have the ability to log in to Windows machines. Some users may start off as Linux-only users, but then need to be given access to Windows machines later. The smbldap tools don't handle this case very well. However, the smbldap tools do handle other things nicely, so like all things, investigate all the tools available and choose the best one(s) suited to your needs.

We need several users in LDAP that will do various tasks. First we need a user who has write access to certain pieces of the directory. If you notice in /etc/samba/smb.conf, there is an option, ldap admin dn, that defines the DN of this user. This user, named samba_server, should be stored in the LDAP directory itself, and it will be the only user in the directory with a password associated with it. Because this user isn't of the posixAccount objectClass, the account is not recognized under Linux. To create this user, first run slappasswd to generate the hashed password. Then, take the hash and create an ldif file that's similar to Listing 3.

Next, we need to tell Samba how to access the LDAP directory as samba_server user by using the smbpasswd command:

# /usr/bin/smbpasswd -w <password> Setting stored password for ↪"uid=samba_server,ou=people,o=ci,dc=example,dc=com" ↪in secrets.tdb

For added security, you should turn off your shell's history logging as the password is given on the command line. The smbpasswd command takes the password given and stores it in /var/lib/samba/private/secrets.tdb keyed to the Samba domain and the admin dn, so if either of those values change, you need to rerun smbpasswd.

Because Samba uses this user to query and modify values in the directory, we need to allow the Samba admin write access to certain attributes in the directory, so make sure to add the appropriate ACLs to /etc/openldap/slapd.conf.

At this point, we can get the SID for our domain. To obtain the domain's SID, you need to be root on the primary domain controller (PDC) for the domain, and run:

# net getlocalsid SID for domain CI-PDC is: ↪S-1-5-21-2162541494-3670296480-3949091320

If you won't be using the smbldap tools to create all of the Samba LDAP entries, you need to use this SID when creating those. I've included a sample LDIF containing all the entries you need to create in the on-line Resources.

Samba also needs a user with uid 0 in the LDAP directory temporarily to perform certain actions. The entry need not be a full posixAccount user, but it should look like Listing 4.

Notice that this user entry does have an NT password, but this password need not be the same as the actual root password, and it's only temporary to get rights assigned to normal users. I've included a simple Perl script in the on-line Resources that you can use to generate the NT password hashes that are needed. You need the Crypt::SmbHash and Term::ReadKey Perl modules to use it.

The last user to modify is your own, so that it's recognized as a Samba user and is a Domain Admin. Listing 5 shows the LDIF.

You'll notice that this account also has an NT password in the LDAP directory. Unfortunately, as of this writing, Samba has no stable support for using Kerberos authentication unless Samba is authenticating against an AD server. There are ways, however, to store Kerberos principal data in an LDAP directory if you're using the Heimdal Kerberos implementation. This potentially could make Samba authentication a little bit cleaner, though it won't make your Samba domain an AD server. Because we're not using Heimdal and this isn't officially supported, we must store Samba passwords in the directory. I've provided some links in the on-line Resources on the Kerberos/LDAP solution if you're interested.

We're now ready to start Samba, but make sure you also start the winbind service as well. Under Gentoo, modify /etc/conf.d/samba.

With Samba v3.0.11, the notion of privileges was introduced. Prior to this version, a network-accessible uid 0 user was required for all user, group, machine and printer management. As of v3.0.11, a user with the proper privileges can initiate these types of requests. A uid 0 user is still necessary eventually for some of these, but it no longer need be network-accessible. So, you might be wondering why we added a uid 0 account to the directory. Well, there's a bit of a chicken-and-egg problem when initially setting up Samba. In order to perform these special operations, you need the proper privileges, but you can't grant yourself those privileges without having those privileges. So, to grant a normal user those privileges, you need the uid 0 user briefly, and then you can remove it from the directory. To find out which privileges your version supports, you can use the net command:

# net rpc rights list -U root

Password:

SeMachineAccountPrivilege Add machines to domain

SePrintOperatorPrivilege Manage printers

SeAddUsersPrivilege Add users and groups to the domain

SeRemoteShutdownPrivilege Force shutdown from a remote system

SeDiskOperatorPrivilege Manage disk shares

Newer versions have added more privileges so make sure you know all that your version supports before proceeding. Now we need to assign privileges to groups and/or users. The obvious first step is to grant all privileges to the Domain Admins group:

# net rpc rights grant "CI\Domain Admins" \ SeMachineAccountPrivilege SePrintOperatorPrivilege \ SeAddUsersPrivilege SeRemoteShutdownPrivilege \ SeDiskOperatorPrivilege -U root Password: Successfully granted rights.

At this stage, we should be able to remove the root user from the directory, because any member of the Domain Admins group should be able to issue administrative Samba commands.

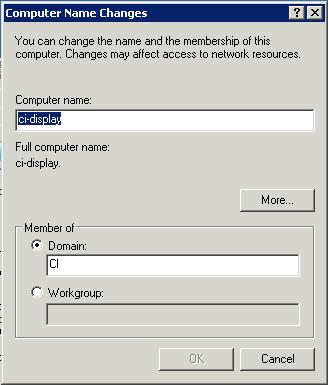

So we have a Samba user but really nowhere for this user to login to. In the Windows world, machines must join the domain for user domain accounts to be valid. When a machine joins the domain, it needs to create a domain account for itself. This account looks exactly like a regular user account except that it ends with a dollar sign. Because I don't use the smbldap tools, I wrote a small Perl script that reads the admin dn's password from the secrets.tdb and adds the machine account to the LDAP directory. The script is available from the on-line Resources and depends on the Crypt::SmbHash, Net::LDAP, File::Temp and TDB_File Perl modules. Once you have this script in place, you can add the machine to the domain by right-clicking on My Computer, choosing Properties, choosing the Computer Name tab and then clicking on the Change... button. Enter an appropriate computer name if one isn't already provided, then choose the Domain: option in the Member of field and enter your Samba domain name (Figure 1). Once you click OK, it will ask you for a user name and password. Enter the user name and password for the user that is a member of the Domain Admins group—leggett, in my case. After a few moments, you should receive a message that welcomes you to the domain. Once you reboot, you'll have the chance to log in as a domain user.

Figure 1. Joining the Domain

Although it's fine that you now have Windows machines plugged in to your infrastructure, this article is also about single sign-on. You might ask ask yourself “But authentication isn't being served by Kerberos, so how will single sign-on work?” MIT has a Kerberos for Windows package that allows you to obtain and manage tickets similar to Apple's Kerberos.app (Figure 2).

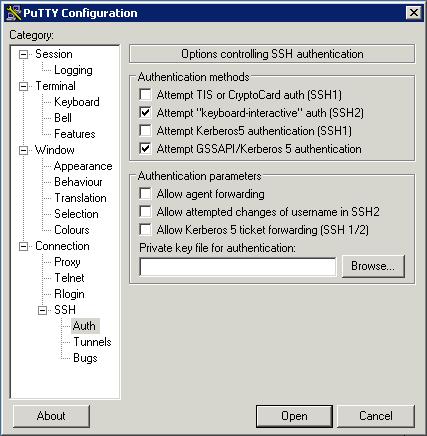

The two main needs for single sign-on are SSH access and mail access. Certified Security Solutions has patched the PuTTY SSH client for Windows to allow GSSAPI authentication. In order to use the MIT Kerberos for Windows under Windows 2000 and XP systems, copy the file plugin_mitgss.dll to plugingss.dll in the PuTTY install directory. Once you fire up PuTTY, go to the Auth menu in the Connection/SSH category and check Attempt GSSAPI/Kerberos 5 authentication (Figure 3). Make sure you have valid Kerberos credentials, and away you go.

Figure 3. PuTTY GSSAPI Configuration

The last major piece to get working is mail access. Microsoft does not use GSSAPI as its authentication scheme. Instead it uses what is called SPNEGO. Because of this, Outlook and Outlook Express will not work with our single sign-on environment. But there's good news. Qualcomm's Eudora e-mail package supports GSSAPI, and it has a free version to boot.

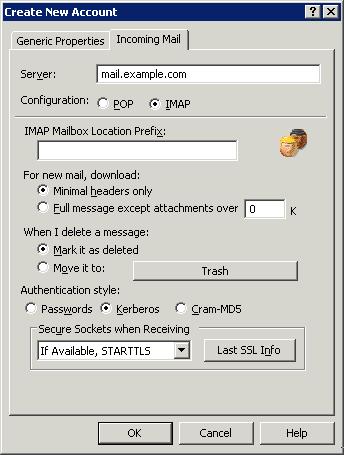

Start the account creation process, and choose Skip directly to advanced account setup. Enter the required information for the SMTP and IMAP settings. Make sure to choose If Available, STARTTLS for the Secure Sockets settings, and under the Incoming Mail tab, make sure to select Kerberos as the authentication style (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Eudora Account Creation

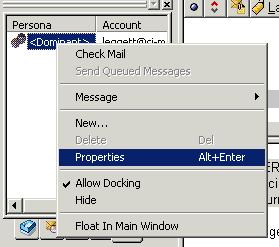

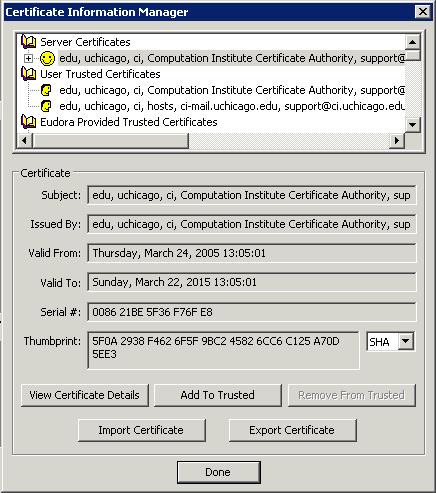

Once you've gotten your account configured, you may get an error the first time you try to connect saying that either the connection has broken or GSSAPI failed. These errors aren't very descriptive of the actual problem, which is that Eudora doesn't trust your self-signed SSL certificates. To fix this, edit the properties for your newly created personality (Figure 5). Click on the Incoming Mail tab, then the Last SSL Info button, and then the Certificate Information Manager button (Figure 6). If you click the Add To Trusted button, your self-signed certificate will be trusted by Eudora as valid. You need to do this for your SMTP server as well the first time you try to send mail.

Figure 5. Eudora Personality Properties

Figure 6. Eudora Certificate Information Manager

You now have integrated one more major architecture into your single sign-on and corporate directory infrastructure. There are still some pieces that could be added or enhanced, such as a way to keep passwords in sync between Kerberos and Samba, LDAP searches in Eudora and more-robust Samba user management scripts. However, you can see how Kerberos and LDAP can make administration and use of your system much easier and more unified. In my last article in this series, I'll explore some ways to think about using your new infrastructure for administrative functions. Until then, keep expanding and using your corporate directory!

This work was supported by the Mathematical, Information, and Computational Sciences Division subprogram of the Office of Advanced Scientific Computing Research, Office of Science, U.S. Department of Energy, under Contract W-31-109-ENG-38.4:08.

Resources for this article: /article/8701.