This has been one crazy month. Why? Because I've discovered the weird-science world of Binaural Beats. For the uninitiated (which I'm guessing you are), binaural beats are basically just two sound streams running against each other, but usually for a very specific purpose: brain wave entrainment.

The way it works is you'll have an audible base frequency, say 200Hz. Then you have a beat frequency, which usually will be below what your ear can hear, say 8Hz. You then run the carrier frequency down both sides of the stereo spectrum (and this is best on headphones), but with a slight difference on one channel from the other (in this example, 200Hz down the left, and 208Hz down the right). When you hear these played, your brain concentrates on the 8Hz difference, or whatever beat frequency you're running.

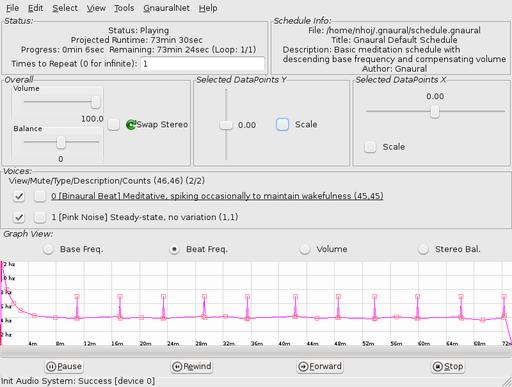

Gnaural can help slow down or speed up your brain waves—here it's being used for inducing a meditative state.

Why would you do this, you ask? Because these binaural frequencies can have strange and unique effects on your body and state of consciousness. This really is weird stuff, and the program we're looking at using is Gnaural, made by my good friend from Yale Psychology, Bret Logan. According to its Web site:

Gnaural is a multiplatform programmable binaural-beat generator, implementing the principle of binaural beats as described in the October 1973 Scientific American article “Auditory Beats in the Brain” (Gerald Oster)....In over a decade of experience with the technique, I have found it mainly useful in areas of sleep induction and “power napping”, and also as a way to bring meditation both within reach (when stress has put it out of reach) and to extend its boundaries over time.

Installation

Provided on the Web site are packages specifically for Debian; however, there are packages natively available for Ubuntu, Fedora, SUSE, Gentoo and Arch Linux. There are two versions available: Gnaural and Gnaural 2. I'm not sure what the difference is (maybe it's that they use GTK 1 and 2—they look the same to me), but Gnaural 2 is obviously the latter, so I've stuck with that. When I went to install the binaries, there were no dependency issues, so they installed right away.

If you're working with source, you'll need the -dev packages for libglade2, libportaudio and libsndfile. If you download the tarball, extract it, and enter the folder with the command line, apparently the installation is the usual case of:

$ configure $ make $ sudo make install

However, I had problems with conflicting Portaudio versions and couldn't get past the ./configure script, so better luck to you if you're compiling the source (I just stuck with the binary). Once Gnaural is installed, you can start it at the command line with:

$ gnaural2

Usage

Before you do anything, plug in some decent headphones. When Gnaural loads, you'll see a bunch of controls and a field with a strange graph. This is Gnaural's default pattern, a playlist of binaural frequencies. This default pattern is designed to be “Meditative, spiking occasionally to wakefulness”, and it has a default play time of 73.5 minutes, which safely will fit on any audio CD. If you're patient, press Play and go for it. Otherwise, you might want to scale back the runtime to something you can easily hack, say ten minutes or so (check the Scale box under Selected Datapoints X, and drag the slider left to do this).

Now, I must state from the outset, this is nothing to do with New Age stuff. Gnaural is purely scientific in its methods, and it uses only two sound waves running against each other. When it refers to meditation, although someone who meditates in the traditional sense would find use here, in this case, it's purely to do with slowing down the brain and relaxing—shutting off parts that needn't be running for the moment. This default pattern will take you through various stages of consciousness by entraining your brain to certain frequencies.

In the background, “pink noise” will be playing, which is a sort of soft static that helps drown out noise from the outside world. This can be muted if you like, which generally will make the effect of the binaural sounds stronger and more apparent. I haven't really got the space to go into much further detail here, but explore, and you'll find that you can make your own frequencies and design your own patterns, among many other features.

In terms of bodily effects, generally it will make you feel more relaxed and probably sleepy—that's the desired effect of the default pattern. However, on experiments with myself and my friends, I found I had strange REM-like eye movements and rapid blinking. One friend had momentary changes in vision. Another seemed to lose track of time. One got really sleepy. Our guitarist felt amazingly relaxed, and his brother said it felt like his ears were shrinking. And, one of my mates said it felt like his tongue was slowly disappearing!

The uses of binaural beats aren't limited purely as a tool of relaxation though. If you have a bit of a trawl around the Web site's discussion boards, you can find other presets for things, such as staying alert, helping you wake up, maintaining concentration while studying and helping travel times pass quickly.

These usually sub-audible frequencies have different effects on different people—everyone's brain is unique. I'd like to say this is harmless, but that would be irresponsible. This is still a fairly unexplored area of science. If you try it, do so at your own risk, and if you have negative effects, stop using it immediately. On the other hand, you also might find it's brilliant, soothing and love every minute of it, and some people are using binaural beats every day for this very reason. Check it out, but take care.

Ever made a mistake, deleted or overwritten something, and wanted to go back a day? This might be the tool for you. According to the project's Freshmeat entry:

Back In Time is a simple backup system for Linux (GNOME and KDE4) inspired by the flyback project and TimeVault. The backup is done by taking snapshots of a specified set of directories. All you have to do is configure where to save the snapshot, what directories to back up, and when a backup should be done (manually, every hour, every day, every week or every month). It acts as a user-mode backup system. This means you can back up and restore only folders to which you have write access.

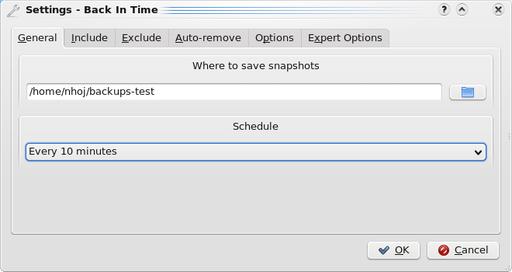

Back In Time lets you decide how often you want to back up your folders and where, in handy folder snapshots.

Installation

If you check out the Web site's download page, it has instructions to integrate repositories for Ubuntu and Fedora, where you can install the packages straight from your system's package manager. If you don't have either of these distros though (or prefer to compile it), the source is available too. The link where these are found is misleadingly marked “You can download older versions here” on the main downloads page (you actually can get the latest source tarballs from this section too, newer than the main binaries).

If you're going with the binaries, you'll have to install the available common package first, and then install either the GNOME or KDE4 package, depending on your preference. If you choose to run with the source tarball, installation is surprisingly easy. Download the tarball, extract it, and open a terminal in the folder. Enter the command:

$ sudo ./install-common.sh

This first step installs the base of the program (not the GUI) and requires that you have Python and rsync installed.

If you want to run with GNOME, enter:

$ sudo ./install-gnome.sh

It now will be ready to run under GNOME and requires python-glade2, python-gnome2 and meld.

For KDE, enter:

$ sudo ./install-kde4.sh

The KDE option requires x11-utils, python-kde4 (>= 4.1) and kompare. Once the installation is finished, you can run the program by entering:

$ backintime

Usage

Once you're inside, Back In Time is a pretty basic affair. On a first-time run, it starts off with the Settings Dialog, where you define where the backup snapshots are saved, what folders to back up and how often to do it (among other features).

Start with where to back up. You'll see the General tab first, and the first field will let you choose where to save the snapshots of what you want backed up. Below that is the drop-down box for how often you want snapshots updated, which has the choices of disabled (you'll have to do it yourself), every five minutes, ten minutes, hour, day, week or month. I've got mine set to every ten minutes. It checks to see whether there are any folder differences, and if so, it takes another snapshot.

Click on the Include tab, and you can define what actual folders you want backed up in your snapshots. I've got my desktop being backed up in snapshots, which are in the form of separate folders in my home directory, under backups. Every time there's a change, a new folder is made, each with a different date and time code, allowing me to backtrack accurately if I need to retrieve something. Other tabs include more advanced options, such as excluding certain files and the like, but I'll let you explore that yourself.

All in all, Back In Time is a very simple application that is best used on smaller folders that you work with a lot. As a musician with my own recordings, I have a lot of music files being constantly altered, and quite often, I make silly mistakes that result in files being irretrievable. Back In Time is invaluable for such circumstances. If you're chasing something super-advanced with a lot of wizz-bang features that work system-wide, this probably isn't it, but for those who want something simple for use on a small scale, it's ideal.