GNOME and KDE may be the heavy-hitters of the desktop world, and although all that power is nice, sometimes it's too bulky. That's where other desktop managers come in.

It's dangerous for me to use sports metaphors, because my expertise ends at knowing there are three strikes in an out. When it comes to sitting the bench, however, I'm a veteran professional! Most major distributions choose one of the big hitters for their desktop management systems. GNOME and KDE continue the epic battle that keeps the competition intense and our desktops diverse. In honor of this month's Desktop issue, I thought it would be nice to pay some homage to those desktop managers and windows managers that don't get quite as much attention.

Before we delve too deep into comparing the various Linux GUIs out there, it's important to understand the difference between window managers and desktop managers. The nuances between the two can be subtle and at times almost nonexistent. A window manager is simply the program running on top of the X server itself that manages windows. Some are very sparse in their features, and some are so robust they approach the usability of a full-blown desktop manager.

So, what is a desktop manager, you ask? Well, it's more of a total user-interaction interface. It often includes applications, widgets and system integration. In fact, desktop managers (or desktop environments, as they're sometimes called) include a window manager as part of their arsenal. So, although GNOME is a desktop manager, part of the GNOME environment includes Metacity, which is a window manager GNOME uses for, well, managing its windows. It's possible to run a Linux system with only a window manager, as I talk about later, but usually a Linux distribution comes with some sort of desktop manager installed by default.

Ubuntu and Kubuntu certainly are the first-string players for Canonical's Linux lineup. Granted, with Ubuntu 11.04, its flagship product will switch from using a standard GNOME interface to the Unity shell normally used only in its Netbook product, but at least historically, Ubuntu has used GNOME, and Kubuntu has used KDE. Canonical also has its official Xubuntu version for older or less-powerful hardware. Xubuntu runs the XFCE desktop manager. Although it does require fewer resources than GNOME or KDE, many still think XFCE is rather bloated for slower hardware. There is another option, Lubuntu, but it's not officially supported by Canonical. Instead of XFCE, Lubuntu uses the LXDE desktop environment. The Lubuntu team claims to be much less resource-intensive, so I installed them both to see how they “feel” in everyday use.

Xubuntu's install is pretty much like every other flavor of Ubuntu. In fact, it's pretty much like every other flavor of Linux. Gone are the days of difficult installs, and even if you choose to use a text-based installer, the process is dead simple—so simple, in fact, it's silly to include a screenshot. It looks like an installer. Trust me.

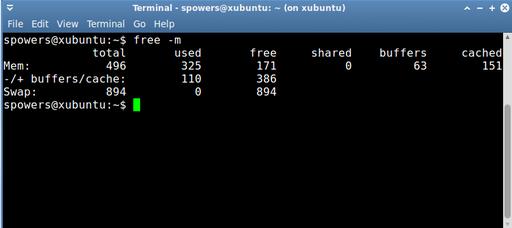

Current versions of Xubuntu are a little shocking in just how much they resemble their GNOME-y counterparts. In fact, the Xubuntu desktop in version 10.10 looks like a slightly bluer version of Ubuntu 10.10. Certainly this is Canonical's tweaking—a very nice job of making its lighter-on-the-resources desktop look exactly like its big brother. Unfortunately, appearance isn't the only place Xubuntu is identical to Ubuntu. Figure 1 shows a freshly booted install of Ubuntu, with no programs running other than the terminal displayed. You can see the freshly booted new install uses approximately 328MB of the 512MB installed on my machine. When I turned to the Xubuntu install, which runs XFCE instead of GNOME, I expected to see a much lower memory usage upon booting up. I was shocked to see Xubuntu using 325MB, almost identical to the Ubuntu install (Figure 2).

Figure 2. A freshly booted, default install of Xubuntu 10.10 uses 325MB of RAM—almost identical to Ubuntu.

The big difference with Xubuntu isn't really how much RAM the desktop manager uses, but rather the default applications installed. When I start Xubuntu's Exaile music application versus Ubuntu's Rhythmbox, it does indeed use less RAM, and it starts up faster. However, getting rid of Rhythmbox on Ubuntu and installing Exaile in its place gives the same advantage while using GNOME under Ubuntu. In fact, although Xubuntu and XFCE do feel faster in use, in every case I've tested, it seems to be due only to the default applications. If you're a GNOME fan, Xubuntu might be a big change for little reward. Keep GNOME, install some faster applications, and you might get the best of both worlds.

It turns out I'm not the only person to notice that Xubuntu doesn't really tailor itself to low-end hardware as much as it claims to. The folks in charge of the Lubuntu Project decided improving performance for slower machines should include more than installing zippy applications by default. Just like with Xubuntu, Lubuntu installs in an extremely unexciting and completely functional way. Once installed, however, Lubuntu does differ from Xubuntu and Ubuntu in appearance.

Although a similar blue to Xubuntu, Lubuntu's screen layout is visually different. Figure 3 shows Lubuntu's simple single taskbar layout, which is quite similar to the design Microsoft has been trying to perfect since the days of Windows 95. That's not a bad thing. As a group we may not care for Microsoft, but its start-menu-type system is widely known and very usable. The first thing I did upon booting Lubuntu was open a terminal and check the memory usage. You can see in Figure 4 that Lubuntu is using only 163MB of RAM when fully booted. That's almost exactly half the RAM Xubuntu and Ubuntu use when freshly booted. When you add to that the selection of fast and small applications Lubuntu uses by default, including the Chromium Web browser, it really does scream even on low-end or old computers. If you've been frustrated with your computer's poor performance with either GNOME under Ubuntu or XFCE under Xubuntu, you may want to give Lubuntu a try. It uses the same repositories, and it has remarkable compatibility with more well-known, if not bulkier, applications.

There are more to the alternatives than just speed. I used the Ubuntu example above to demonstrate how alternatives to the “Big 2” can give you advantages in speed, but there are other reasons to veer from the norm as well. The ROX Desktop, for example, is a complete desktop environment designed around a file manager—the ROX-Filer, to be specific. Although the ROX Desktop is certainly light on system resource needs, its design and integration with the filesystem is what really makes it unique. Figure 5 shows a screenshot of Puppy Linux, which uses ROX-Filer as the file manager.

The ROX Desktop suite includes its own window manager, OroboROX, but like most other desktop environments, it doesn't rely on one specific window manager to work. When you find a window manager you like, it's often possible to use it seamlessly with whatever desktop management system you want. In fact, many people, and even entire distributions, run only a window manager. This is possible because many window managers are so feature-rich, they do most of the things a desktop manager would do. One good example of that is Enlightenment.

Enlightenment is a window manager that has been around a long time. Some window managers are minimalistic; however, Enlightenment is extremely feature-rich. It provides a file manager, a dock, a GUI configuration tool, application launchers—pretty much everything required in a full-blown desktop environment. Does that mean it's a desktop manager and not just a window manager? Perhaps. It doesn't really matter how you define it though. Enlightenment is one of those things everyone should try at least once. There are even live CDs, specifically designed for trying Enlightenment. Figure 6 shows applications running under the Elive CD default desktop.

IceWM is another window manager that is rather profound in the features it offers. Although it doesn't have a mechanism for creating desktop icons, it does have a very robust menu system and application suite for managing most aspects of the Linux desktop. IceWM is very customizable, and although it uses the familiar Windows-like start menu, it doesn't try to clone Microsoft. In fact, I use a combination of IceWM and Nautilus on my network of 150 older thin clients because it's fast and reliable. Because the menu system is controlled with a single system-wide config file, it makes wide-scale customization a breeze.

A multitude of Linux distributions have only a window manager to manipulate the desktop. Blackbox, Fluxbox and Openbox are all related window managers. Fluxbox is a fork of Blackbox, and although Openbox is all original code now, it started as a fork of Blackbox as well. These three window managers are lightning fast. They may not offer the same level of features and complexity that Enlightenment or IceWM do, but for many minimalistic distributions, they are just perfect. CrunchBang Linux is a prime example of a full-featured, yet minimalistic distribution. It uses Openbox as its window manager, and as you can see in Figure 7, the windowing environment is designed to get out of the user's way.

The great thing about choosing a Linux GUI is that it costs you nothing to change. Whether you like Fedora's default GNOME install or prefer openSUSE's green-lizard KDE install, every Linux install can be tweaked or changed. I must warn you though, once you try the NeXTSTEP clones Window Maker or AfterStep, you might never want to see a start menu again. If you experiment with the mouseless beauty of the Ratpoison window manager, you might never want to click again. Or, perhaps you're at the other end of the spectrum, and you want to fool yourself or others into thinking you are running OS X. Check out the free Macbuntu GNOME theme. With Linux, customization is king, and the options are seemingly endless. I created a chart to help you sort out some of the Linux GUI options available (see Table 1). It's by no means an exhaustive list, but it should get you started. Remember, just because a desktop environment is sitting on the bench doesn't mean it didn't make the team. Check out the bench-warmers, you might just find a winner.

Table 1. A Sampling of Linux Desktops/Window Managers

| Desktop/Window Manager | Description | Design Goals | Based On | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KDE | Full desktop environment | Full system integration, including applications | Uses KWin window manager and Qt libraries | Great application integration, highly customizable | Distinct look; non-KDE apps often seem awkward |

| GNOME | Full desktop environment | Full system integration, including applications | Uses Metacity window manager, based on GTK+ libraries | Wide variety of native applications, wide adoption in corporate environments | Non-GTK apps often look odd and use more RAM |

| LXDE | Lightweight desktop environment | Speed and beautiful interface | Uses Openbox window manager and GTK+ libraries | Works well on older/slower hardware, maintains compatibility | Lacks some of the features found in GNOME or KDE |

| XFCE | Lightweight desktop environment | Full-featured desktop environment, but light on resources | Usually uses XFWM4, but works well with other window managers | Somewhat lower system requirements than GNOME or KDE | Possibly a bit too resource-hungry for low-end systems |

| Enlightenment E17 | Window manager with the features of a desktop manager | Speed and eye candy with integrated functionality | A window manager plus a set of libraries for developing apps | Fast without sacrificing style | Still in beta but quite stable |

| ROX Desktop | Desktop manager based on the ROX-Filer | Approaches the OS in a file-centric way | ROX-Filer file manager and the OroboBox window manager | Unique file-based design makes installing apps drag and drop | ROX Desktop is either a love or hate affair |

| IceWM | Hybrid window manager and desktop manager | Speed and simplicity | Simple menu and taskbar design | Fast and easy to make system-wide configuration changes | No way to make desktop icons, requires additional software for some features |

| Blackbox/Fluxbox | Very minimalistic window managers | Speed and small memory/CPU footprint | Fluxbox is based on Blackbox (it's a fork) | Blazingly fast | Very limited in features, but by design not immaturity |

| Openbox | Very minimalistic window manager | Speed and small memory/CPU footprint | Originally based on Blackbox, original code since version 3.0 | Simple and fast | Limited in features by design |

| AfterStep/Window Maker | Clones of the NeXTSTEP interface | Functions and looks like NeXTSTEP | Designed after the unique design of the NeXTSTEP interface | Unique | Often difficult to configure, and the interface is an acquired taste |

| Ratpoison | A window manager that doesn't require a mouse | Kills the need for a mouse | Designed after GNU Screen | No need for a mouse | Very limited in features, which the developers consider a feature |

| DWM | An extremely minimalist window manager | Manages windows and nothing more | The ideas of other minimalist window managers | Small and fast | No configuration files, must edit source code to configure |