I've never covered a subproject of something I've reviewed before, but I noticed this a few weeks ago when trawling the Tor site (I've no idea how I missed it until now). It seemed so important that I instantly gave it top billing for this month's column.

Tor has become increasingly famous/infamous in the past few months due to its use by Web sites like WikiLeaks, as well as its crucial role in getting information out to the world during the recent Egyptian revolution.

For those unfamiliar with Tor, LJ has covered it before—see Kyle Rankin's article “Browse the Web without a Trace” in the January 2008 issue and my New Projects column in the April 2010 issue. But to recap, the Tor Web site sums it up nicely:

The Tor software protects you by bouncing your communications around a distributed network of relays run by volunteers all around the world: it prevents somebody watching your Internet connection from learning what sites you visit, it prevents the sites you visit from learning your physical location, and it lets you access sites that are blocked.

However, in standard form, Tor is a rather cumbersome beast, with all sorts of background process dæmons, complex configuration files, startup services and so on. Even if you're a pretty advanced user, there's still a good chance of something going wrong somewhere, delaying your chance to jump on-line securely. This is where the Tor Browser Bundle comes to the rescue:

The Tor Browser Bundle lets you use Tor on Windows, Mac OS X or Linux without needing to install any software. It can run off a USB Flash drive, comes with a pre-configured Web browser and is self-contained. The Tor IM Browser Bundle additionally allows instant messaging and chat over Tor.

Before I continue, the Web site offers a caveat that LJ readers probably will find more important than most: “Note that the Firefox in our bundles is modified from the default Firefox; we're currently working with Mozilla to see if they want us to change the name to make this clearer”.

Extending your options greatly, the Vidalia Control Panel is a great tool when using Tor.

Installation

Although the bundle was designed to run on a Flash drive, that needn't be the case. Like many others, I simply saved this to hard drive and ran it from there. Feel free to do the same if you're so inclined.

As for installing the bundle (well, sort of), the Tor people were good enough to offer the following instructions, saving me a lot of trouble:

Download the architecture-appropriate file above, save it somewhere, then run: tar -xvzf tor-browser-gnu-linux--dev-LANG.tar.gz (where LANG is the language listed in the filename), and either double-click on the directory or cd into it, then execute the start-tor-browser script. This launches Vidalia, and once that connects to Tor, it launches Firefox.

Usage

Before continuing, this bundle is designed to run on machines that don't have Tor installed. If you do have Tor installed and running, stop the process and then you can carry on.

Now, with the Browser Bundle running, first the Vidalia control panel will start, which is designed to establish a Tor connection as well as manage various Tor options using a GUI front end. I recommend exploring the Vidalia control panel, as it has neat features, such as bandwidth monitoring, network viewer, settings dialog and more.

Provided all has gone well, Firefox should start and will try to load a Web page. This Web page takes a while to load—don't worry; the Tor network is pretty slow at the best of times, and if everything worked, you'll soon have a message that says in big green letters: “Congratulations. Your browser is configured to use Tor.”

From here, you can browse like you would any other day, but the uninitiated may be in for a shock. Most modern Web sites have fancy scripts and Flash objects, and these very features are what causes the greatest security holes. Hence, Tor's browser disables these scripts by default. Chances are that the only Web sites that will work without hassle are deliberately minimalist in their design.

However, don't worry. If you look at the screen's bottom right, you'll see an icon with a blue S. Click on that icon, and you can choose either to enable scripts for this particular Web site or enable scripts globally (not recommended for the security reasons just mentioned).

Those willing to take the risk can choose new default settings for security in the preferences, available under Edit→Preferences. Given the nature of this project, the default settings are understandably set for paranoia. If you're undertaking work that involves a serious security risk, be very careful with what you enable or disable. If you're unsure of the risk you're taking, perhaps a more secure, minimalist and less-script-reliant Web service would be a better choice for your activities (assuming an alternative is available, of course).

Something I couldn't get working under the Linux version was Flash in general. My older brother said he used Tor to watch some overseas TV shows not available in Australia and inaccessible to those with IP addresses external to a certain country. He was using the Windows version of Tor, and I'm guessing that he would've used the Browser Bundle, instead of setting up a machine with Tor permanently installed. The content he was viewing was Flash-based, so he must have been able to enable it for such a session.

I realize that Flash presents a security risk, but many people will want to use the Tor Browser Bundle for something as trivial as watching international TV shows—not really the sort of thing that will have the authorities kicking down your front door. If any readers out there know how to get Flash running with the Linux bundle, feel free to drop me an e-mail. I'd love to hear from you!

Moving back onto more serious topics, in journalism in particular, projects such as Tor will become increasingly indispensable in moving information beyond borders and protecting user privacy against prying eyes. When I last tried Tor, it gave me a headache and was far from intuitive in its use. However, a clever little bundle such as this gives Tor's power of anonymity to those with average PC skills, and regardless of its use, that's an important thing.

If you're watching your weight, monitoring your health and dietary habits, or simply unconvinced by flashy food labels that don't tell the whole story, this is the project for you. According to the Web site:

I have written open-source free nutrition software, NUT, which records what you eat and analyzes your meals for nutrient levels in terms of the “Daily Value”, or DV, which is the standard for food labeling in the US. The program uses the free food composition database from the USDA. This free nutritional analysis software was written for UNIX systems (I use Linux), but it can be compiled on just about any system with a C compiler. (To get a free C compiler, Windows people might look at Cygwin or MinGW, and Mac people might look at xcode.) By experimenting with NUT, you can find the optimal level of the various nutrients and how to implement this with foods available to you. NUT can help reconstruct the lost instruction manual to your care and feeding, because, when the authorities and crackpots disagree on the proper human diet, you can design an experiment using the food composition tables to discover the truth!

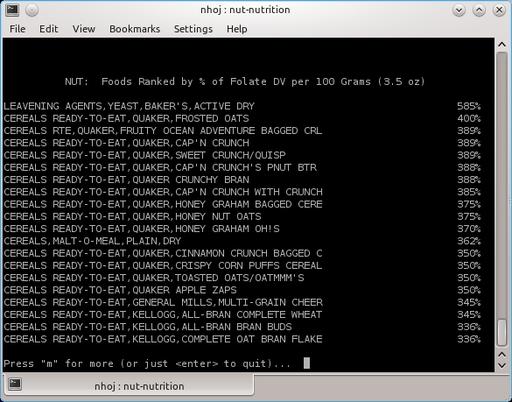

NUT has an extensive database of food statistics, worth the price of admission alone (console version pictured).

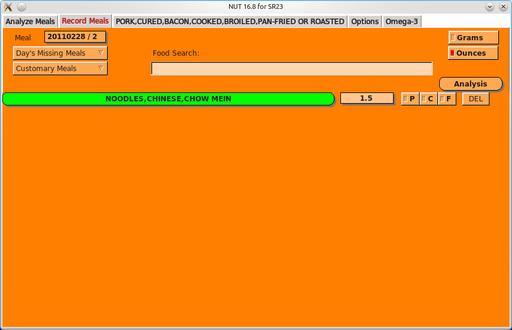

The NUT GUI makes using this program much less tiresome and displays other forms of information simultaneously. Here's the stats for bearded seal oil.

One of the main reasons for using NUT is recording your daily meals and then running detailed analysis against them.

Installation

I'm unsure of other distributions, but binaries are available for Debian and Ubuntu. I run with the usual source option here. Grab the latest source tarball, extract it, and open a terminal in the new folder. At the time of this writing, NUT didn't have an install script, so you'll need to do a number of steps manually. Assuming the /usr/local folders are fine for installation, issue the following commands as root:

# mkdir /usr/local/lib/nut/ # mv raw.data/* /usr/local/lib/nut/

If your distro uses sudo (such as Ubuntu), simply prefix those commands with the sudo command.

Once this step is out of the way, compile the program with:

$ make

If the compiling goes well, you should be able to use the console program immediately. Simply enter the command:

$ ./nut

This runs the console program, which I look at in the next session. As for the GUI program, that needs to be compiled separately.

Change into the flkt directory by entering:

$ cd fltk

And again, enter the command:

$ make

I ran into compilation problems when I first tried to compile the fltk component (hence, yesterday I was going to cover only the console program). I'm not sure what I did to get it working, but I think it was downloading fltk 1.3 manually from the fltk Web site, then compiling and installing it separately. If you manage to get it compiled, you can run the GUI program now by entering:

$ ./Nut

Note the capital letter above—it's the differentiator between the GUI and command-line programs.

If you'd like quick access to NUT, copy the executables into bin folders. If you're still in the fltk directory, change back into the main directory of the nut folder:

$ cd ..

Next, enter these commands as either root or sudo:

# mv nut /usr/local/bin/ # mv nut.1 /usr/local/man/man1/ # mv fltk/Nut /usr/local/bin

Now you either can run the command-line version with nut or the GUI with Nut.

Usage

Unfortunately, the long installation instructions haven't left me much room to cover the actual usage of NUT, but thankfully, things are pretty simple to use.

The console version uses a series of number-driven menus to navigate between functions and foods. For instance, option 1 is for recording meals, followed immediately by a prompt for the date, the meal number and, finally, the name of the food.

Entering the name of the food needn't be precise, as NUT's main strength is its database. Long lists of premade choices exist, and each choice has detailed information regarding a food's nutritional value, such as protein, carbohydrates, specific vitamins and so on.

Head back into the main menu, and more options exist, such as an analysis of your meals and food suggestions, trend plotting and so on, but most people will want to look at options 4 and 6. Here you can browse the extensive database, comparing nutritional values of all sorts of food and drink to your heart's content. The entries are extensive—everything from Red Bull to bearded seal meat.

As for the GUI, I'm not 100% sure, but it appears to have more options than the console version, such as reset controls and the ability to control various ratios. Perhaps I missed them in the console version, but either way, there's definitely more on the screen, more of the time. Plus, everything is broken down into tabs, making the whole process more intuitive, saving the user from navigating endless submenus.

All in all, this is a very clever program despite the currently long-winded installation process. Once those issues are ironed out, NUT will be a seriously nifty nutrition program.