Some of you probably have played audio files from the terminal with one-line commands, such as play, or even used the command line to open a playlist in a graphical music player. Command-line integration is one of the many advantages of using Linux software. This is an introduction for those who want the complete listening experience—browsing, managing and playing music—without leaving the text console.

Thanks to the Ncurses (New Curses) widget library, developers can design text user interfaces (TUIs) to run in any terminal emulator. An Ncurses application interface is interactive and, depending on the application, can capture events from keystrokes as well as mouse movements and clicks. It looks and works much like a graphical user interface, except it's all ASCII—or perhaps ANSI, depending on your terminal. If you've used GNU Midnight Commander, Lynx or Mutt, you're already familiar with the splendors of Ncurses.

An intuitive interface, whether textual or graphical, is especially important in a media player. No one wants to sift through a long man page or resort to Ctrl-c just to stop an annoying song from playing on repeat, and most users (I'm sure some exceptions exist among Linux Journal readers) don't want to type out a series of commands just to ls the songs in an album's directory, decide which one you want to hear and play it, and then play a song in a different directory. If you've ever played music with a purely command-line application, such as SoX, you know what I'm talking about. Sure, a single command that plays a file is quite handy; this article, however, focuses on TUI rather than CLI applications. For many text-mode programs, Ncurses is the window (no pun intended) to usability.

Note to developers: if you want to write a console music player, take advantage of the Curses Development Kit (CDK), which includes several ready-made widgets, such as scrolling marquees and built-in file browsing.

Now, on to the music players!

Mp3blaster was the first console music player I ever used. That was in 2007, by which time it already was a mature and full-featured application. Its history actually dates back to 1997, before the mainstream really had embraced the MP3 format, let alone the idea of an attractive interface for controlling command-line music playback. Back then, it was humbly known as “Mp3player”.

Despite the name, Mp3blaster supports several formats besides MP3s. Currently, these include OGG, WAV and SID. Keep an eye out for FLAC support in the future, as it is on the to-do list in the latest source tarball.

One nice feature of Mp3blaster is the top panel showing important keyboard shortcuts for playlist management. You can scroll through this list using + and -. There is also a useful chart on the right side that shows ASCII art playback symbols (such as |> for play) above their respective shortcut keys. Press ? for detailed help.

You can customize any of the keybindings in your configuration file, which is usually located at ~/.mp3blasterrc. I had to change several of these in order to use Mp3blaster in GNOME due to conflicts with my global hot keys. Mp3blaster's default keybindings are better suited for use without X.

Herrie, meaning “clamour” in Dutch, was first released in 2006. Somehow it has escaped mention in many articles on console music players, but the Herrie community group on the music Web site Last.fm shows true fan dedication.

Herrie is great for Last.fm users because it's so easy to set up track scrobbling. Most of the music players in this article support scrobbling in some capacity—it's all open-source software, after all, and in theory, you can write a script to make anything do anything—but configuration is exceptionally simple with Herrie. All you have to do is put your user name and password in your ~/.herrie/config/herrie.conf file. Note that the password should not be in plain text; rather, you should type in the output of printf %s p4ssw0rd | md5 as stated in the configuration file itself.

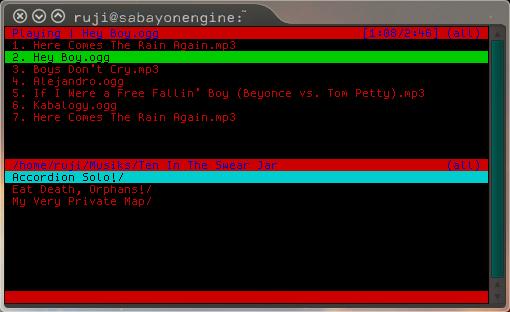

Figure 2. Herrie shows the current playlist on top and a file browser on the bottom.

Music on Console (MOC) is a good choice for music libraries that consist of OGG, WAV and MP3 files. It's easy to use out of the box, boasting a two-paned interface similar to that of Midnight Commander, with a file browser on the left and your playlist on the right. The default keybindings are intuitive—mostly single letters that stand for what they do, such as n for “next track” and R to toggle random play, so command-line newbies need not fear any Emacs-style digital acrobatics.

MOC is my go-to Linux music player these days. It's fast and slick, and it looks just how I want now that I've edited my ~/.moc/config file to adjust the colors and the widths of each window pane. Another plus is its support for the JACK Audio Connection Kit (JACK).

The command to start MOC is mocp.

If Emacs-style digital acrobatics are your modus operandi, check out Bongo and the Emacs Multi-Media System (EMMS). Both media players run inside Emacs and provide similar functionality. The main difference is that EMMS is designed to run unobtrusively in the background, while Bongo emphasizes the user interface.

Bongo and EMMS are written in Emacs Lisp. You can install them the same way you'd install any other Emacs package; this may vary from distro to distro, but no matter what operating system you're using, you'll probably end up editing some Lisp configuration files. One of the first things to configure is your list of back ends. These programs don't actually do the dirty work of playing your music files; rather, they are front ends for other programs.

You can link any back end of your choice to a file type as well as pass custom command-line arguments. For example, one of the back ends Bongo recognizes by default is mpg123. If you want it to use, say, mpg321 instead, it's just a matter of editing that line in your configuration file or using Emacs to access Bongo's built-in customization dialog with M-x customize-group RET bongo RET. You can add a custom back end with a few lines such as these:

(define-bongo-backend mpg321

:pretty-name "MPG-Thr33-Tw0-0ne"

:extra-program-arguments '("--loop 0")

:matcher '(local-file "mp3" "wav"))

Although I use Emacs from time to time, I'm no guru; I admit that the time I spent with Bongo was flustering. For instance, I pressed Return to start playing a track—easy enough—but then realized I didn't know how to turn it off. I entered M-x apropos RETURN bongo and read through the list of Bongo commands until I found the one I needed: M-x bongo-stop. The GitHub home page reveals that you also can stop playback immediately with C-c C-s, and there are other key combinations for fancier tricks, such as 3 C-c C-s to stop playback after the next three tracks finish playing.

That example is a fair representation of my whole experience with Bongo so far. It can be scary if you don't know your way around Emacs very well, but it's extremely powerful and full of options that you'd probably never thought of before.

If you're a Vi/Vim fanatic, consider Vimmpc and Vimp3.

In the vast universe of Linux audio, the Music Player Dæmon (MPD) could be considered a red giant. Chances are you've at least heard of it if you've done any research on playing music in Linux. It comes preinstalled in many distributions, and I have yet to find a major repository that doesn't include it.

MPD is technically a server-side application; it's great for setting up networked audio in a home media center. You also can use it simply for local playback. The advantage here is that you can use any client you want to control MPD, and there are many from which to choose. I easily could devote pages to discussing MPD, but that's beyond the scope of this article. Documentation is easy to find on-line.

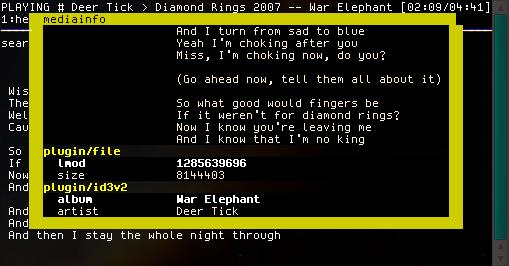

Now, let's move on to Ncmpcpp. This is an Ncurses MPD client, based on Ncmpc but more advanced. It includes support for Last.fm scrobbling and music visualization via external libraries. Lyrics fetching and display are built in and can be activated for a selected track by pressing l. The lyrics feature is, in fact, what attracted me to Ncmpcpp in the first place. I'd tried various scripts to fetch lyrics in other console music players, particularly MOC, but nothing worked for me until Ncmpcpp. Ncmpcpp can fetch artist information as well.

Although Ncmpcpp is terrific once you get it set up, using an MPD client to listen to music isn't always a pragmatic choice. You'll most likely be up and running much faster with a player like Mp3blaster, MOC or Herrie.

I'm someone who likes to experiment with various Linux distributions by installing them on old computers and in virtual machines, and I often test out software in these environments. The truth about MPD is that a lot can go wrong. I let out a (silent) cheer every time I manage to install and use it successfully. Grappling with dependencies is half the battle, and configuring your system, especially your ~/.mpdconf file, is the other half. I've gotten it to work on some systems without a hitch, but more often than not, I've encountered problems and solved them through trial and error.

Don't let this discourage you; MPD and its wide selection of clients are worth the effort to set up if you take advantage of their features, and there are plenty of places to get help if you need it. The MPD man page is essential reading; beyond that, read through the official wiki and forums. Your distribution may provide documentation as well. Gentoo's on-line wiki, for instance, has a lengthy section on MPD.

Like MPD, XMMS2 is a dæmon you can control over a network, and there are various clients for it. The XMMS2 Wiki acknowledges that the developers of these two applications have similar goals and that a collaboration could eventually be possible. For now though, they are separate packages with separate clients. Two text-mode XMMS2 clients that caught my attention were Kuechenstation and CCX2.

Kuechenstation is one 1337 music player. Okay, I was being mostly facetious there, but take one look at it, and you'll think “eighties demoscene”. (Kuechenstation actually has been around only since 2008.) It uses the FIGlet library to display the current song title in a scrolling marquee of oversized letters made from ASCII characters.

The whole interface is attractive and friendly. You can navigate through several full-screen modes using keybindings that are helpfully listed at the bottom of the screen. These modes include playlist mode, artist information mode and podcast mode, to name a few. The podcast feature is especially notable; I haven't seen podcast support in any of the other music players discussed in this article. Kuechenstation helps you get started with a few pre-subscribed feeds, which are all in German.

The Kuechenstation configuration file is located at ~/.config/xmms2/clients/kuechenstation.conf. There you can choose your podcast subscriptions, interface colors and even the scrolling FIGlet font.

CCX2, written in Python, is another solid XMMS2 client. Its command mode will come naturally to Vi/Vim users. All the standard playback and playlist management features are there: search, rename, browse, metadata display and so forth.

So why did I decide to write about two TUI XMMS2 clients instead of just choosing the one with more features? My reasoning is, first of all, that the interfaces of Kuechenstation and CCX2 are quite different, and each will appeal to different users solely on the basis of personal taste. Second, each has a major feature that the other lacks. CCX2 doesn't come with podcast support as Kuechenstation does, but it does support lyrics fetching out of the box, which Kuechenstation does not.

Figure 8. One of CCX2's Lyrics Display Layouts

I suggest trying them both. They are young and in active development, so there's a reasonable chance that a feature you're missing could be added in the future. And, of course, if you're a developer, you can try to add it yourself.

The famous VLC media player, known for its ability to play almost any media file you throw at it, comes with a lesser-known Ncurses control interface. To start it up, type nvlc. The interactive features are noticeably limited in comparison with the vast array of options you may be used to seeing in the GUI version. Press B to browse your files and Return to add a file to the playlist. Toggle help view with h for a complete list of hot keys.

At first glance, nvlc doesn't seem all that special. It might not be for you if you want a player that's preconfigured with a hefty arsenal of hot keys, but you can do a lot with it—including adding custom hot keys—if you're willing to experiment.

The path to nvlc's power is through command-line arguments. You can pass arguments ranging from a directory or playlist (a la, nvlc /path/to/my/music) to complex chains of filters. Anything you can do in the GUI version of VLC is possible with nvlc if you know which arguments to pass.

Hint: enter nvlc -h for basic help, which is actually quite lengthy, or nvlc -H for even lengthier help. Enter nvlc --list to see what modules are available in your installation or nvlc --list-verbose for more-detailed output.

For starters, try:

nvlc --audio-filter chorus_flanger --delay-time 150 ↪--dry-mix 0.8 --wet-mix 0.6 --feedback-gain -0.3 ↪/path/to/my/music.fileextension

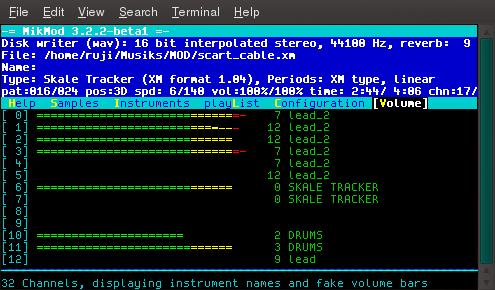

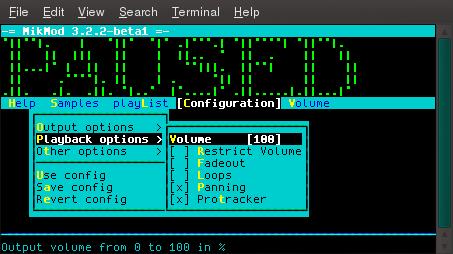

For the old-schoolers among you who collect modules—and perhaps scoff when you hear the phrases “MP3 player” and “music player” used interchangeably—there is MikMod. MikMod is an old standby from pre-Windows Microsoft DOS. You can use it as a back end for other applications, such as Bongo or EMMS in Emacs, or as a standalone module player.

MikMod will play many module formats. If your file extensions include MOD, XM, IT or S3M, you're in luck. Sorry, MP3s—no MikMod for you, or for all you WAVs and OGGs and AIFFs. In a way, this is a bit sad, because I'd love to play my standard music files in a player as awesome as MikMod. I have to keep in mind that many of MikMod's features, such as on-the-fly tempo change and instrument-specific volume bars, are built specifically for module file formats. Perhaps this will be an incentive for me to make some sounds in MilkyTracker.

Figure 10. Instrument Levels in MikMod

Figure 11. Some of MikMod's Options

Many console music players are available for Linux. I chose the few I covered in this article based on my level of experience with them and on what I considered to be unique and notable features. If the topic intrigues you, go out (or Google) and explore.