Want a 3-D printer but are overwhelmed with all the options? Find out what printer best suits your personality and pocketbook.

I've been interested in 3-D printers ever since I saw one at a Maker Faire a few years ago, but it was only a year ago when I started seriously thinking about having one of my own. At that point, I started to realize just how many different options existed and ultimately started researching the RepRap family of 3-D printers (more on the different printer families below). After about a year of research, I finally settled on a printer that fit my needs and my budget.

During my research, I found that 3-D printing was an even more vast world than I imagined before. Not only are there lots of choices with the hardware, even when it comes to the software, you have a lot of options. In this article, I give a general overview of 3-D printing hardware, and then in my next article, I will discuss some of the current most popular software to control your printer. So if you have thought about getting into 3-D printing and were wondering how it works with Linux, these columns should give you a good overview from the perspective of someone who's relatively new to 3-D printing himself.

When most geeks talk about 3-D printing, they are talking about some method to create three-dimensional objects much like a regular printer. Although most hobbyist 3-D printers work with plastic, there also are efforts to print in all sorts of other materials from metals to ceramics to organic materials. Even if you narrow things down to talking only about 3-D printing in plastic, there still are all sorts of methods 3-D printers can use. That said, basically all of the home 3-D printers operate via plastic extrusion. If you have used a hot-glue gun before, you know that you load the back of the gun with a large glue stick, and once the tip of the gun heats up, your trigger forces the glue stick toward the hot end of the gun where it extrudes in a much narrower blob of glue. Imagine taking a three-dimensional object and slicing it into layers as thick as the hot glue from your hot-glue gun, and then imagine carefully squeezing the hot glue out onto a surface layer by layer until you got your object.

Plastic extrusion works in a similar way to a hot-glue gun except your plastic comes in the form of a long filament of ABS or PLA plastic 1.75mm or 3mm in diameter. The 3-D printer's extruder forces the filament into the hot end of the printer, which heats up enough to melt the plastic (160–190°C is average for PLA, and 200–250°C for ABS). The melted plastic is then pushed through a much narrower nozzle (.5mm to .35mm normally) onto a print bed.

If all a 3-D printer did was melt plastic like a hot-glue gun, it would be great for creating blobs of melted plastic but not much else. What makes the 3-D printer useful is that this extruder is mounted on a stable frame with precise X, Y and Z axis motors controlled by custom electronics. When you send a 3-D diagram to the printer, it is sliced into individual layers, and each layer is represented by a series of X, Y and Z movements, along with instructions to extrude or retract the plastic filament at appropriate points. The result is that your object is printed layer on top of layer.

If you are new to 3-D printing, the number of options available can be overwhelming at first. Not only do many of the printers look relatively different from each other, there also is a wide range of prices for 3-D printer kits, from around $500 to more than $2,000 (which is much better than $15,000+ for commercial models). Plus, if you are resourceful, you even can bypass the kits and source all your own parts—it's more effort on your part, and there's a greater chance something might not work, but you can cut down the cost rather dramatically in some cases.

What I've found in my research is that 3-D printers are a lot like Linux distributions. If you were to ask everyone who had 3-D printers which one to get, you'd get about as many replies as if you asked all the Linux users what distribution to use. Some 3-D printers appeal to newbies, and others appeal to experienced users. Some 3-D printers focus on how open their hardware and software is, and others take a more commercial approach. Sound familiar?

I'm not going to enumerate every single 3-D printer out there, so I'm sorry if I leave out your favorite one, but I've found when you look at what 3-D printers the majority of people use, they tend to fall in two big categories: laser-cut wooden-box 3-D printers and RepRap-based printers. Like with Linux distributions, the 3-D printers I'm discussing generally follow open-source principles not just in their software but also in their hardware. Also note that although in some cases you can spend extra to get a pre-assembled kit, most of the kits I mention come unassembled and will require many hours to assemble and calibrate.

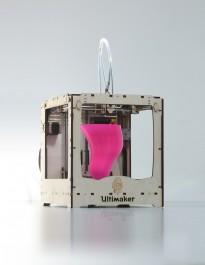

The first category of printer is most identifiable by the fact that the whole printer is enclosed in a wooden box that's usually created by a laser cutter. Printers that fit this category include the MakerBot family of printers, the Ultimaker and the Mosaic printer from MakerGear. Although all of these printers are different, they generally appeal more to people who are new to 3-D printing and want a more-polished appearance to their printer. This more polished appearance means more parts, and unlike the RepRap family of printers, most people who go this route buy a kit with a complete set of parts, and as a result, the price can be higher, starting at $900 for an unassembled Mosaic kit to $2,000 for an all-bells-and-whistles dual-extruder MakerBot Replicator. If you have the money, you can get a nice-looking 3-D printer in this category that functions well, but just don't assume that the extra money necessarily buys you better specs. Think of it like buying a commercial Linux distribution versus downloading a community-supported one.

Ultimaker (photo from blog.ultimaker.com)

MakerGear (photo from www.makergear.com)

MakerBot Replicator (photo from store.makerbot.com/replicator.html)

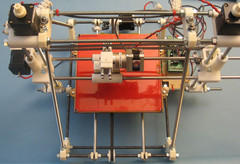

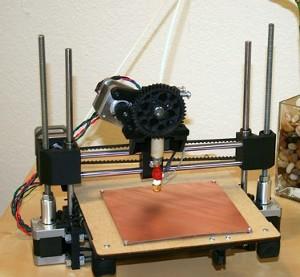

If the wooden-box 3-D printers are like commercial Linux distributions, you can think of the RepRap family like Debian. RepRap is a community-driven project that aims to build a 3-D printer that can create many of its own parts and self-replicate. Because of the community-focused design process, anyone can propose improvements or new RepRap derivatives, and successful designs get rewarded with popularity. There are a number of generations of RepRap designs, but the Prusa Mendel seems to be the design most people in the RepRap community recommend to newbies today. The community also has built incremental improvements and additions to the design—many of which you can download from 3-D printer design sharing sites like www.thingiverse.com and print out yourself, so you can continue to improve your printer as you use it.

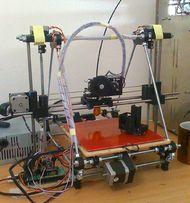

As you might expect, there are a number of different ways to acquire a RepRap, starting with sourcing your own parts on-line from published bills of materials on the RepRap Wiki to buying completed kits from other members of the RepRap community on eBay. Some members of the RepRap community have even gone on to start their own businesses selling RepRap parts, including sites like lulzbot.com, makergear.com and printrbot.com, the latter being a new Kickstarter-funded company that sells a low-cost RepRap derivative that has a more-simplified design.

Printrbot (photo from printrbot.com)

Although the RepRap is as capable (some would argue more capable) when compared to the wooden-box printers, people tend either to love or hate the simplified metal-rod design. The simplified design results in a lower cost in general though, with self-sourced RepRaps as cheap as $400 or $500, a complete Printrbot kit starting at $550, and complete Prusa Mendel kits usually starting around $800 or so.

Prusa (photo from www.makergear.com/products/3d-printers)

So what printer should you choose? That's like asking what Linux distribution you should use. As with Linux distributions, it really comes down to people's personalities and what they want to accomplish. For instance, the RepRap community is full of people who love to build and calibrate 3-D printers and tinker with them to get the most out of them, so if you are the kind of person who likes to fine-tune and tinker with your Linux distribution, that class of printers may be right up your alley. On the other hand, the laser-cut wooden-box 3-D printers seem to appeal more to folks who don't find tinkering with the 3-D printer itself as appealing and are more interested in printing objects. If you are the kind of person who leans more toward the commercial Linux distributions that focus more on working out of the box, these printers might appeal to you more. In my case, I bought a basic Printrbot kit because I tended to lean more toward the RepRap side of things as far as tinkering went, but in particular, the simplified design and the lower overall price to get started on the Printrbot appealed to me.