Thwart would-be attackers by hardening your SSH connections.

If you need remote access to a machine, you'll probably use SSH, and for a good reason. The secure shell protocol uses modern cryptography methods to provide privacy and confidentiality, even over an unsecured, unsafe network, such as the Internet. However, its very availability also makes it an appealing target for attackers, so you should consider hardening its standard setup to provide more resilient, difficult-to-break-into connections. In this article, I cover several methods to provide such extra protections, starting with simple configuration changes, then limiting access with PAM and finishing with restricted, public key certificates for passwordless restricted logins.

As defined in the standard, SSH uses port 22 by default. This implies that with the standard SSH configuration, your machine already has a nice target to attack. The first method to consider is quite simple—just change the port to an unused, nonstandard port, such as 22022. (Numbers above 1024 are usually free and safe, but check the Resources at the end of this article just to avoid possible clashes.) This change won't affect your remote users much. They will just need to add an extra parameter to their connection, as in ssh -p 22022 the.url.for.your.server. And yes, this kind of change lies fully in what's called “security through obscurity”—doing things obscurely, hoping that no one will get wise to your methods—which usually is just asking for problems. However, it will help at least against script kiddies, whose scripts just try to get in via port 22 instead of being thorough enough to try to scan your machine for all open ports.

In order to implement this change, you need to change the /etc/ssh/sshd_config file. Working as root, open it with an editor, look for a line that reads “Port 22”, and change the 22 to whatever number you chose. If the line starts with a hash sign (#), then remove it, because otherwise the line will be considered a comment. Save the file, and then restart SSH with /etc/init.d/sshd restart. With some distributions, that could be /etc/rc.d/init.d/sshd restart instead. Finally, also remember to close port 22 in your firewall and to open the chosen port so remote users will be able to access your server.

While you are at this, for an extra bit of security, you also could add or edit some other lines in the SSH configuration file (Listing 1). The Protocol line avoids a weaker, older version of the SSH protocol. The LoginGraceTime gives the user 30 seconds to accomplish a login. The MaxAuthTries limits users to three wrong attempts at entering the password before they are rejected. And finally, PermitRootLogin forbids a user from logging in remotely as root (any attacker who managed to get into your machine still would have to be able to break into the root account; an extra hurdle), so would-be attackers will have a harder time at getting privileges on your machine.

Be sure to restart the SSH service dæmon after these changes (sudo /etc/init.d/sshd restart does it) and, for now, you already have managed to add a bit of extra safety (but not much really), so let's get down to adding more restrictions.

Your machine may have several servers, but you might want to limit remote access to only a few. You can tweak the sshd_config file a bit more, and use the AllowUsers, DenyUsers, AllowGroups and DenyGroups parameters. The first one, AllowUsers, can be followed by a list of user names (or even patterns, using the common * and ? wild cards) or user@host pairs, further restricting access to the user only from the given host. Similarly, AllowGroups provides a list of group name patterns, and login is allowed only for members of those groups. Finally, DenyUsers and DenyGroups work likewise, but prohibit access to specific users and groups. Note: the priority order for rules is DenyUsers first, then AllowUsers, DenyGroups and finally AllowGroups, so if you explicitly disallow users from connecting with DenyUsers, no other rules will allow them to connect.

For example, a common rule is that from the internal network, everybody should be able to access the machine. (This sounds reasonable; attacks usually come from outside the network.) Then, you could say that only two users, fkereki and eguerrero, should be able to connect from the outside, and nobody else should be able to connect. You can enable these restrictions by adding a single line AllowUsers *:192.168.1.*,fkereki,eguerrero to the SSH configuration file and restarting the service. If you wanted to forbid jandrews from remote connections, an extra DenyUsers jandrews would be needed. More specific rules could be added (say, maybe eguerrero should be able to log in only from home), but if things start getting out of hand with too many rules, the idea of editing the ssh configuration files and restarting the server begins to look less attractive, and there's a better solution through PAM, which uses separate files for security rules.

If you google for meanings of PAM, you can find several definitions, ranging from a cooking oil spray to several acronyms (such as Power Amplitude Modulation or Positive Active Mass), but in this case, you are interested in Pluggable Authentication Modules, a way to provide extra authentication rules and harden access to your server. Let's use PAM as an alternative solution to specify which users can access your server.

From a software engineering viewpoint, it would just be awful if each and every program had to invent and define and implement its own authentication logic. How could you be certain that all applications did implement the very same checks, in the same way, without any differences? PAM provides a way out; if a program needs to, say, authenticate a user, it can call the PAM routines, which will run all the checks you might have specified in its configuration files. With PAM, you even can change authentication rules on the fly by merely updating its configuration. And, even if that's not your main interest here, if you were to include new biometrics security hardware (such as fingerprint readers, iris scanners or face recognition) with an appropriate PAM, your device instantly would be available to all applications.

PAMs can be used for four security concerns: account limitations (what the users are allowed to do), authorization (how the users identify themselves), passwords and sessions. PAM checks can be marked optional (may succeed or fail), required (must succeed), requisite (must succeed, and if it doesn't, stop immediately without trying any more checks) and sufficient (if it succeeds, don't run any more checks), so you can vary your policies. I don't cover all these details here, but rather move on to the specific need of specifying who can (or cannot) log in to your server. See the PAM, PAM Everywhere sidebar for a list of some available modules.

PAM configurations are stored in /etc/pam.d, with a file for each command to which they apply. As root, edit /etc/pam.d/sshd, and add an account required pam_access.so line after all the account lines, so it ends up looking like Listing 2. (Your specific version of the file may have some different options; just add the single line to it, and that's it.) You'll also have to modify the sshd configuration file (the same one that you modified earlier) so it uses PAM; add a UsePAM yes line to it, and restart the sshd dæmon.

The account part is what is important here. After using the standard UNIX methods for checking your password (usually against the files /etc/passwd and /etc/shadow), it uses the module pam_access.so to check if the user is in a list, such as shown in Listing 3. Both account modules are required, meaning that the user must pass both checks in order to proceed. For extra restrictions, you might want to look at pam_listfile, which is similar to pam_access but provides even more options, and pam_time, which lets you fix time restrictions. You also would need to add extra account lines to the /etc/pam.d/sshd file.

You need to edit /etc/security/access.conf to specify which users can access the machine (Listing 3). Each line in the list starts with either a plus sign (login allowed) or a minus sign (login disabled), followed by a colon, a user name (or ALL), another colon and a host (or ALL). The pam_access.so module goes down the list in order, and depending on the first match for the user, it either allows or forbids the connection. The order of the rules is important. First, jandrews is forbidden access, then everybody in the internal network is allowed to log in to the server. Then, users fkereki and eguerrero are allowed access from any machine. The final -:ALL:ALL line is a catchall that denies access to anybody not specifically allowed to log in in the previous lines, and it always should be present.

Note that you could use this configuration for other programs and services (FTP, maybe?), and the same rules could be applied. That's an advantage of PAM. A second advantage is that you can change rules on the fly, without having to restart the SSH service. Not messing with running services is always a good idea! Using PAM adds a bit of hardening to SSH to restrict who can log in. Now, let's look at an even safer way of saying who can access your machine by using certificates.

Passwords can be reasonably secure, but you don't have them written down on a Post-It by your computer, do you? However, if you use a not-too-complex password (so it can be determined by brute force or a dictionary attack), then your site will be compromised for so long as the attacker wishes. There's a safer way, by using public/private key logins, that has the extra advantage of requiring no passwords on the remote site. Rather, you'll have a part of the key (the “private” part) on your remote machine and the other part (the “public” part) on the remote server. Others won't be able to impersonate you unless they have your private key, and it's computationally unfeasible to calculate. Without going into how the key pair is created, let's move on to using it.

First, make sure your sshd configuration file allows for private key logins. You should have RSAAuthentication yes and PubkeyAuthentication yes lines in it. (If not, add them, and restart the service as described above.) Without those lines, nothing I explain below will work. Then, use ssh-keygen to create a public/private key pair. By directly using it without any more parameters (Listing 4), you'll be asked in which file to save the key (accept the standard), whether to use a passphrase for extra security (more on this below, but you'd better do so), and the key pair will be generated. Pay attention to the name of the file in which the key was saved. You'll need it in a moment.

Now, in order to be able to connect to the remote server, you need to copy it over. If you search the Internet, many sites recommend directly editing certain files in order to accomplish this, but using ssh-copy-id is far easier. You just have to type ssh-copy-id -i the.file.where.the.key.was.saved remote.user@remote.host specifying the name of the file in which the public key was saved (as you saw above) and the remote user and host to which you will be connecting (Listing 5). And you're done.

In order to test your new passwordless connection, just do ssh remote.user@remote.host. If you used a passphrase, you'll be asked for it now. In either case, the connection will be established, and you won't need to enter your password for the remote site (Listing 6).

Now, what about the passphrase? If you create a public/private key pair without using a passphrase, anybody who gets access to your machine and the private key immediately will have access to all the remote servers to which you have access. Using the passphrase adds another level of security to your log in process. However, having to enter it over and over again is a bother. So, you would do better by using ssh-agent, which can “remember” your passphrase and enter it automatically whenever you try to log in to a remote server. After running ssh-agent, run ssh-add to add your passphrase. (You could run it several times if you have many passphrases.) After that, a remote connection won't need a passphrase any more (Listing 7). If you want to end a session, use ssh-agent -k, and you'll have to re-enter the passphrase if you want to do a remote login.

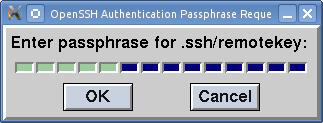

You also may want to look at keychain, which allows you to reuse ssh-agent between logins. (Not all distributions include this command; you may have to use your package manager to install it.) Just do keychain the.path.to.your.private.key, enter your passphrase (Figure 1), and until you reboot the server or specifically run keychain -k all to stop keychain, your passphrase will be stored, and you won't have to re-enter it. Note: you even could log out and log in again, and your key still would be available. If you just want to clear all cached keys, use keychain --clear.

Figure 1. By entering your passphrase once with keychain, it will be remembered even if you log out.

If you use a passphrase, you could take your private keys with you on a USB stick or the like and use it from any other machine in order to log in to your remote servers. Doing this without using passphrases would just be too dangerous. Losing your USB stick would mean automatically compromising all the remote servers you could log in to. Also, using a passphrase is an extra safety measure. If others got hold of your private key, they wouldn't be able to use it without first determining your passphrase.

Finally, if you are feeling quite confident that all needed users have their passwordless logins set up, you could go the whole mile and disable common passwords by editing the sshd configuration file and setting PasswordAuthentication no and UsePAM no, but you'd better be quite sure everything's working, because otherwise you'll have problems.

There's no definitive set of security measures that can 100% guarantee that no attacker ever will be able to get access to your server, but adding extra layers can harden your setup and make the attacks less likely to succeed. In this article, I described several methods, involving modifying SSH configuration, using PAM for access control and public/private key cryptography for passwordless logins, all of which will enhance your security. However, even if these methods do make your server harder to attack, remember you always need to be on the lookout and set up as many obstacles for attackers as you can manage.