Vagrant can be overwhelming, but don't let that stop you from taking advantage of this awesome tool.

I admit it, some tools confuse me. I know they must be amazing, because programs don't get popular by being dumb (well, reality TV, but that's another story). I have the same sort of confusion with Vagrant that I have with Wine, Docker, Chef and countless other amazing tools people constantly rave about. So in this article, I'm going to break down Vagrant into its simplest form.

Don't get me wrong, I could follow along with the tutorials and get a virtual machine running by typing the magic vagrant up command. The thing is, I really don't like magic when it comes to computers. I like to know what is happening, why it's happening and where to look when things go wrong. Ultimately that's my goal, to be able to fix it when it breaks. Without an understanding of how things truly work, it gets really scary when the magic button quits working.

Simply put, Vagrant is a front end to an underlying virtualization program. By default, the back-end program is VirtualBox, although Vagrant can work with other underlying virtualization systems. This realization was important for me, because the line between what had to be inside VirtualBox and what Vagrant actually did on its own was murky. If you use Vagrant, you don't ever need to start VirtualBox—truly. It won't hurt anything if you do start it, but Vagrant uses VirtualBox more like a tool than a system.

Another reason this is important is because it means there is no intermingled dependencies between Vagrant and VirtualBox. By that I mean you can take your Vagrantfiles to another computer, and it will work just fine. It simply will use the copy of VirtualBox you have installed on the new computer and work exactly the same.

Much like brushing your teeth with a hairbrush doesn't make much sense, using Vagrant for setting up your permanent data center might not be the best idea. Sure, you could use it, but Vagrant really excels at building VMs very fast and destroying them when you're finished. In fact, most people use Vagrant for one of two things: creating a development environment to test their code and creating temporary servers on demand when the workload requires it.

One of the nice side effects of using Vagrant is that it forces you to think of your persistent data as separate from your server. I've found that even in situations where I'm not using Vagrant, I'm now smarter about making sure my data isn't dependent on a single point of failure. An example is my /usr/local/bin folder. Most of my machines have tons of little scripts I've written that live in the /usr/local/bin folder. Since I've been using Vagrant, I think about my scripts as something that should be accessible by my machines, but maybe not stored in the local file space on a server. Sure, I have backups, but if I can keep my data separate from my server filesystem, moving to a new server is much easier.

I already mentioned that Vagrant is a front end to VirtualBox. Of course, VirtualBox already has a command-line interface, but Vagrant is far more powerful. Rather than install an operating system, Vagrant takes a “template” of a fully installed machine and creates a clone. That means you can have a fully running system in seconds instead of going through the installation process. The “templates” are referred to as “boxes” in the Vagrant world, and there's no need to make your own. You can download generic boxes of most Linux distributions, which means zero setup time.

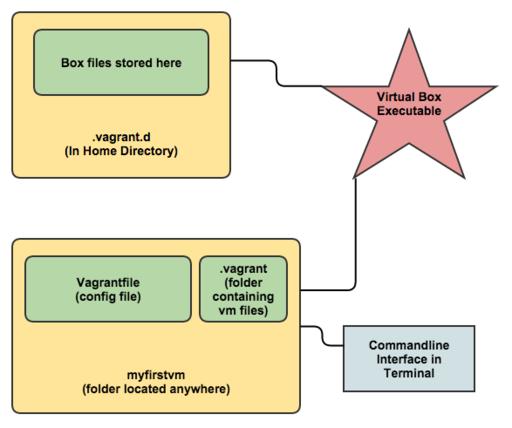

There are three main pieces to the Vagrant puzzle. Figure 1 shows a diagram of those parts and their connection to each other.

Figure 1. There are really only two locations to worry about: the .vagrant.d folder in your home directory and the project folder you create.

1) The Virtualization System:

By default, this is VirtualBox. It is the engine that makes Vagrant boxes work, but it doesn't keep track of any VM files or configuration. It's a bit like using Python. The Python executable needs to be installed, but it's just an interpreter that executes the Python code. With Vagrant, it's the same sort of thing. VirtualBox is just the program Vagrant uses to run its own code. If VirtualBox is installed, your work is done.

2) The .vagrant.d Folder:

This actually took me a while to figure out. Those “boxes” I mentioned earlier are downloaded to this folder so that when you create a new VM, it doesn't have to re-download the box, it just uses your local cached copy. Once I knew where the folder was, it was easier to fix things when I messed up. I tend to learn by experimentation, and so I invariably break things. At first, I couldn't figure out how to get rid of the boxes I incorrectly downloaded, but clearing them out of the .vagrant.d folder in my home directory did the trick.

3) The Project Folder:

My favorite feature of Vagrant is that every VM lives inside its own folder. Everything to do with the VM is in that folder, so you don't have to worry about the configuration file being in one folder, the hard drive image being in another folder and so on. The folder can also be created anywhere, and it functions independently from other project folders. They don't even depend on the original “box” once they're created, because the box is cloned into the project folder when you create the Vagrant instance.

The project folder contains the Vagrantfile, which is the single configuration file for the virtual machine. It contains the settings for what type of hardware you want to have VirtualBox use (how much RAM and so on), and it can contain startup scripts that will customize your VM as it is created. In fact, a common thing to do with the Vagrantfile is to start Chef and automatically configure the entire machine from a Chef server! Thankfully, the Vagrantfile can be very simple, and Vagrant creates one for you by default the first time you create a VM.

I'm almost to the point where most Web tutorials start, which is to create a VM with Vagrant. Now that you know what Vagrant is doing, the process is far more interesting and less mysterious. Here is the step-by-step process:

1) Install VirtualBox and Vagrant:

On a Debian-based distro like Ubuntu, you simply type:

sudo apt-get install vagrant virtualbox

and allow the programs to be installed. There's no need to open VirtualBox, just have it installed.

2) Download a Box File:

This is how you populate the .vagrant.d folder in your home directory with a template or box file. To choose what box you want, head over to vagrantbox.es, and copy the URL of whatever base you want to start with. Lots of contributed boxes are available, so pick one that makes sense for you, and copy the URL to your clipboard. Then, to get the box to your local cache, type:

vagrant box add NAME http://example.com/boxurl/mybox.box

Note that NAME is just an arbitrary name that you pick to name your box. If you go with an Ubuntu 14.04 image, you could name it something like “trusty64” so you can reference it easily later. The command will download the box file and store it with whatever name you chose.

3) Create a Project Folder:

Somewhere on your system, create a folder for the VM. It truly can be anywhere. I usually make it on my desktop at first, so I easily can see it—basically:

mkdir ~/Desktop/myfirstvm

Then, switch into that folder:

cd ~/Desktop/myfirstvm

4) Initialize Your Vagrant Image:

Now you simply type:

vagrant init NAME

The vagrant program will create a Vagrantfile with a default configuration. Basically, it contains information on what box file to use when creating the VM. If you want to do advanced configuration on the Vagrantfile (I'll touch on that later), you can edit it, but by default, it will work with the file untouched.

5) Start Your VM:

The VM configuration file has been created in the myfirstvm folder, but the VM hasn't been created yet. In order to do that, type:

vagrant up

Note that you have to be inside the myfirstvm folder in order to have this work. Because you could have multiple folders with VMs (mysecondvm, for instance), the only way to tell Vagrant what VM you want to start is to be in the correct folder. Vagrant now will create a virtual machine based on the box file you downloaded earlier. The virtual hard drive and all configuration files will be stored in a folder called .vagrant inside the myfirstvm folder (refer back to Figure 1 for details). On the screen, you will see the computer starting, and once it's all set, you have a fully running VM.

6) Do Something with Your VM:

This was another stumbling point for me. I had a running VM, but how to interact with it? Thankfully, Vagrant offers a cool feature, namely SSH. Still inside that myfirstvm folder, type:

vagrant ssh

and you will be logged in via SSH to the running VM! Even though you don't know any passwords on the machine, you always can access it via the vagrant ssh command because Vagrant automatically creates a keypair that allows you to log in without entering a password. Once you're logged in, you can do whatever you want on the system, including changing passwords, installing software and so on.

7) Manipulate Your VM:

After you exit out of your VM, you'll drop back into your local machine inside the myfirstvm folder. The VM still is running, but you can do other things with Vagrant:

vagrant halt — shuts down the VM.

vagrant suspend — pauses the VM.

vagrant resume — resumes a paused VM.

vagrant destroy — erases the VM (not the Vagrantfile).

I hope that makes the Vagrant workflow clear. If it seems simple enough, but not terribly useful, that's about all the basics will get you. Although it's cool to be able to create and destroy VMs so quickly, by itself, the process isn't very useful. Thankfully, Vagrant bakes in a few other awesome features. I already mentioned the vagrant ssh command that allows you to SSH in to the VM instantly, but that is only the tip of the iceberg.

First, you have the /vagrant folder inside the VM. This is a folder that is mounted automatically inside the running VM, and it points to the project folder itself on the main system. So any files you store in “myfirstvm” alongside the Vagrantfile will be accessible from inside the VM in the /vagrant folder. What makes that useful is that you can destroy the VM, create a new VM, and the files in your project folder won't be erased. That is convenient if you want to have persistent data that isn't destroyed when you do a vagrant destroy, but it's even more useful when you combine it with the scripting capability of the Vagrantfile itself.

Admittedly, it gets a little complicated, but the Vagrantfile can be edited using basic Ruby language to automate the creation and bootup of the VM. Here's a simple example of an edited Vagrantfile:

# Sample Vagrantfile with startup script VAGRANTFILE_API_VERSION = "2" Vagrant.configure(VAGRANTFILE_API_VERSION) do |config| config.vm.box = "NAME" config.vm.provision :shell, path: "startup.sh" end

The only line I added was the config.vm.provision line. The other lines were created automatically when I initially typed vagrant init. Basically, what the provision statement does is tell Vagrant that once it starts the VM to execute the startup.sh script. Where does it find the startup.sh file? In that shared space, namely the “myfirstvm” folder. So create a file in your myfirstvm folder alongside the Vagrantfile itself called startup.sh:

# This is the startup.sh file called by Vagrantfile apt-get update apt-get install -y apache2

Make sure the file is executable:

chmod +x startup.sh

Then, have Vagrant create a new VM. If you haven't “destroyed” the existing VM, do that, and then type vagrant up to create a new one. This time, you should see the machine get created and booted, but you also should see the system download and install Apache, because it executes the startup.sh file on boot!

Once I understood how Vagrant can call a script when it creates the VM, I started to realize just how powerful and automated Vagrant can be. And truly, that's just scratching the surface of the things you can do with the Vagrantfile commands. Using that file, you can customize the settings of the VM itself (RAM, CPU and so on); you can create port-forward settings so you can access the Vagrant VM's ports by connecting to your local system's ports (that's actually how vagrant ssh works); and you can configure a VM fully by running a program like Chef when the VM is created.

Vagrant isn't the perfect tool for every job, but if you need a fast, highly configurable virtual machine that can be automated and scripted, it might be the right tool for you. Once I understood how Vagrant worked, it seemed much less like a magic button and much more like an awesome tool. And if you totally mess up your configuration files while you're experimenting? Just erase the files in your /home/user/.vagrant.d/ folder and start with a fresh project folder. All the configuration is done inside the Vagrantfile itself, and even that is created for you automatically when you type vagrant init.

If you want to learn more about the various advanced options Vagrant offers, check out its very nicely organized documentation site: https://docs.vagrantup.com/v2. At the very least, try the example I showed here. It's really cool to see how fast and automated Vagrant makes the entire virtualization experience.