And, how does it compare to what we've already experienced with Linux and open source?

I was in the buzz-making business long before I learned how it was done. That happened here, at Linux Journal. Some of it I learned by watching kernel developers make Linux so useful that it became irresponsible for anybody doing serious development not to consider it—and, eventually, not to use it. Some I learned just by doing my job here. But most of it I learned by watching the term “open source” get adopted by the world, and participating as a journalist in the process.

For a view of how quickly “open source” became popular, see Figure 1 for a look at what Google's Ngram viewer shows.

Ngram plots how often a term appears in books. It goes only to 2008, but the picture is clear enough.

I suspect that curve's hockey stick began to angle toward the vertical on February 8, 1998. That was when Eric S. Raymond (aka ESR), published an open letter titled “Goodbye, 'free software'; hello, 'open source'” and made sure it got plenty of coverage. The letter leveraged Netscape's announcement two weeks earlier that it would release the source code to what would become the Mozilla browser, later called Firefox. Eric wrote:

It's crunch time, people. The Netscape announcement changes everything. We've broken out of the little corner we've been in for twenty years. We're in a whole new game now, a bigger and more exciting one—and one I think we can win.

Which we did.

How? Well, official bodies, such as the Open Source Initiative (OSI), were founded. (See Resources for a link to more history of the OSI.) O'Reilly published books and convened conferences. We wrote a lot about it at the time and haven't stopped (this piece being one example of that). But the prime mover was Eric himself, whom Christopher Locke describes as “a rhetorician of the first water”.

To put this in historic context, the dot-com mania was at high ebb in 1998 and 1999, and both Linux and open source played huge roles in that. Every Linux World Expo was lavishly funded and filled by optimistic start-ups with booths of all sizes and geeks with fun new jobs. At one of those, more than 10,000 attended an SRO talk by Linus. At the Expos and other gatherings, ESR held packed rooms in rapt attention, for hours, while he held forth on Linux, the hacker ethos and much more. But his main emphasis was on open source, and the need for hackers and their employers to adopt its code and methods—which they did, in droves. (Let's also remember that two of the biggest IPOs in history were Red Hat's and VA Linux's, in August and December 1999.)

Ever since witnessing those success stories, I have been alert to memes and how they spread in the technical world. Especially “Big Data” (see Figure 2).

What happened in 2011? Did Big Data spontaneously combust? Was there a campaign of some kind? A coordinated set of campaigns?

Though I can't prove it (at least not in the time I have), I believe the main cause was “Big data: The next frontier for innovation, competition, and productivity”, published by McKinsey in May 2011, to much fanfare. That report, and following ones by McKinsey, drove publicity in Forbes, The Economist, various O'Reilly pubs, Financial Times and many others—while providing ample sales fodder for every big vendor selling Big Data products and services.

Among those big vendors, none did a better job of leveraging and generating buzz than IBM. See Resources for the results of a Google search for IBM + “Big Data”, for the calendar years 2010–2011. Note that the first publication listed in that search, “Bringing big data to the Enterprise”, is dated May 16, 2011, the same month as the McKinsey report. The next, “IBM Big Data - Where do I start?” is dated November 23, 2011.

Figure 3 shows a Google Trends graph for McKinsey, IBM and “big data”.

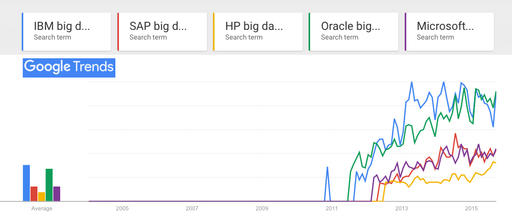

See that bump for IBM in late 2010 in Figure 3? That was due to a lot of push on IBM's part, which you can see in a search for IBM and big data just in 2010—and a search just for big data. So there was clearly something in the water already. But searches, as we see, didn't pick up until 2011. That's when the craze hit the marketplace, as we see in a search for IBM and four other big data vendors (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Google Trends: “IBM big data”, “SAP big data”, “HP big data”, “Oracle big data”, “Microsoft big data”

So, although we may not have a clear enough answer for the cause, we do have clear evidence of the effects.

Next question: to whom do those companies sell their Big Data stuff? At the very least, it's the CMO, or Chief Marketing Officer—a title that didn't come into common use until the dot-com boom and got huge after that, as marketing's share of corporate overhead went up and up. On February 12, 2012, for example, Forbes ran a story titled “Five Years From Now, CMOs Will Spend More on IT Than CIOs Do”. It begins:

Marketing is now a fundamental driver of IT purchasing, and that trend shows no signs of stopping—or even slowing down—any time soon. In fact, Gartner analyst Laura McLellan recently predicted that by 2017, CMOs will spend more on IT than their counterpart CIOs.

At first, that prediction may sound a bit over the top. (In just five years from now, CMOs are going to be spending more on IT than CIOs do?) But, consider this: 1) as we all know, marketing is becoming increasingly technology-based; 2) harnessing and mastering Big Data is now key to achieving competitive advantage; and 3) many marketing budgets already are larger—and faster growing—than IT budgets.

In June 2012, IBM's index page was headlined, “Meet the new Chief Executive Customer. That's who's driving the new science of marketing.” The copy was directly addressed to the CMO. In response, I wrote “Yes, please meet the Chief Executive Customer”, which challenged some of IBM's pitch at the time. (I'm glad I quoted what I did in that post, because all but one of the links now go nowhere. The one that works redirects from the original page to “Emerging trends, tools and tech guidance for the data-driven CMO”.)

According to Wikibon, IBM was the top Big Data vendor by 2013, raking in $1.368 billion in revenue. In February of this year (2015), Reuters reported that IBM “is targeting $40 billion in annual revenue from the cloud, big data, security and other growth areas by 2018”, and that this “would represent about 44 percent of $90 billion in total revenue that analysts expect from IBM in 2018”.

So I'm sure all the publicity works. I am also sure there is a mania to it, especially around the wanton harvesting of personal data by all means possible, for marketing purposes. Take a look at “The Big Datastillery”, co-published by IBM and Aberdeen, which depicts this system at work (see Resources). I wrote about it in my September 2013 EOF, titled “Linux vs. Bullshit”. The “datastillery” depicts human beings as beakers on a conveyor belt being fed marketing goop and releasing gases for the “datastillery” to process into more marketing goop. The degree to which it demeans and insults our humanity is a measure of how insane marketing mania, drunk on a diet of Big Data, has become.

T.Rob Wyatt, an alpha geek and IBM veteran, doesn't challenge what I say about the timing of the Big Data buzz rise or the manias around its use as a term. But he does point out that Big Data is truly different in kind from its predecessor buzzterms (such as Data Processing) and how it deserves some respect:

The term Big Data in its original sense represented a complete reversal of the prevailing approach to data. Big Data specifically refers to the moment in time when the value of keeping the data exceeded the cost and the prevailing strategy changed from purging data to retaining it.

He adds:

CPU cycles, storage and bandwidth are now so cheap that the cost of selecting which data to omit exceeds the cost of storing it all and mining it for value later. It doesn't even have to be valuable today, we can just store data away on speculation, knowing that only a small portion of it eventually needs to return value in order to realize a profit. Whereas we used to ruthlessly discard data, today we relentlessly hoard it; even if we don't know what the hell to do with it. We just know that whatever data element we discard today will be the one we really need tomorrow when the new crop of algorithms comes out.

Which gets me to the story of Bill Binney, a former analyst with the NSA. His specialty with the agency was getting maximum results from minimum data, by recognizing patterns in the data. One example of that approach was ThinThread, a system he and his colleagues developed at the NSA for identifying patterns indicating likely terrorist activity. ThinThread, Binney believes, would have identified the 9/11 hijackers, had the program not been discontinued three weeks before the attacks. Instead, the NSA favored more expensive programs based on gathering and hoarding the largest possible sums of data from everywhere, which makes it all the harder to analyze. His point: you don't find better needles in bigger haystacks.

Binney resigned from the NSA after ThinThread was canceled and has had a contentious relationship with the agency ever since. I've had the privilege of spending some time with him, and I believe he is A Good American—the title of an upcoming documentary about him. I've seen a pre-release version, and I recommend seeing it when it hits the theaters.

Meanwhile, I'm wondering when and how the Big Data craze will run out—or if it ever will.

My bet is that it will, for three reasons.

First, a huge percentage of Big Data work is devoted to marketing, and people in the marketplace are getting tired of being both the sources of Big Data and the targets of marketing aimed by it. They're rebelling by blocking ads and tracking at growing rates. Given the size of this appetite, other prophylactic technologies are sure to follow. For example, Apple is adding “Content Blocking” capabilities to its mobile Safari browser. This lets developers provide ways for users to block ads and tracking on their IOS devices, and to do it at a deeper level than the current add-ons. Naturally, all of this is freaking out the surveillance-driven marketing business known as “adtech” (as a search for adtech + adblock reveals).

Second, other corporate functions must be getting tired of marketing hogging so much budget, while earning customer hate in the marketplace. After years of winning budget fights among CXOs, expect CMOs to start losing a few—or more.

Third, marketing is already looking to pull in the biggest possible data cache of all, from the Internet of Things. Here's T.Rob again:

IoT device vendors will sell their data to shadowy aggregators who live in the background (“...we may share with our affiliates...”). These are companies that provide just enough service so the customer-facing vendor can say the aggregator is a necessary part of their business, hence an affiliate or partner.

The aggregators will do something resembling “big data” but generally are more interested in state than trends (I'm guessing at that based on current architecture) and will work on very specialized data sets of actual behavior seeking not merely to predict but rather to manipulate behavior in the immediate short term future (minutes to days). Since the algorithms and data sets differ greatly from those in the past, the name will change. The pivot will be the development of new specialist roles in gathering, aggregating, correlating, and analyzing the datasets.

This is only possible because our current regulatory regime allows all new data tech by default. If we can, then we should. There is no accountability of where the data goes after it leaves the customer-facing vendor's hands. There is no accountability of data gathered about people who are not account holders or members of a service.

I'm betting that both customers and non-marketing parts of companies are going to fight that.

Finally, I'm concerned about what I see in Figure 5.

If things go the way Google Trends expects, next year open source and big data will attract roughly equal interest from those using search engines. This might be meaningless, or it might be meaningful. I dunno. What do you think?