Maybe now we can make what we should have made with the web in the first place.

I thought my mind was through getting blown until I heard in mid-June 2017 that Brave (https://brave.com) raised $35 million in less than 30 seconds (https://techcrunch.com/2017/06/01/brave-ico-35-million-30-seconds-brendan-eich), though an ICO (Initial Coin Offering: www.investopedia.com/terms/i/initial-coin-offering-ico.asp). I did know ICOs were hot stuff. I also knew Brave's ICO was about to happen, because Brendan Eich (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brendan_Eich), the company CEO, said so over breakfast two days earlier. So my seat belt was fastened, but the acceleration of the ICO still left my mental ass on the pavement two counties back.

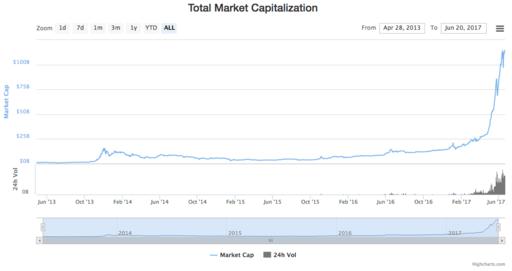

Since then, I've hyper-focused on cryptocurrencies (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cryptocurrency), tokens (tokenfactory.io/smart-beta), distributed ledgers (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Distributed_ledger), ICOs and the rest of it for two reasons. One is that there is a craze going on. See Figure 1.

Figure 1. Crypto Currency Market Capitalizations (coinmarketcap.com/charts)

The other is that the investment here includes a measure of faith that we can once again imagine full agency for individuals as distributed peers on the internet, and that many positive personal, social, economic, political and other transformations will arise from that agency.

Phil Windley, who now chairs the Sovrin Foundation (https://sovrin.org), told me yesterday that this is the third tech revolution of his lifetime. “The first was the PC, and the second was the Internet. This is the third”, he said. I'm inclined to agree, simply because so many of us are seeing a wide open future where before there was just a wall of silos. I lamented that wall here in Linux Journal, way back in September 2011 (www.linuxjournal.com/content/way-ranch):

As entities on the Web, we have devolved. Client-server has become calf-cow. The client—that's you—is the calf, and the Web site is the cow. What you get from the cow is milk and cookies. The milk is what you go to the site for. The cookies are what the site gives to you, mostly for its own business purposes, chief among which is tracking you like an animal. There are perhaps a billion or more server-cows now, each with its own “brand” (as marketers and cattle owners like to say).

This is not what the Net's founders had in mind. Nor was it what Tim Berners-Lee meant for his World Wide Web of hypertext documents to become. But it's what we've got, and it's getting worse.

So I want to share what I'm thinking about this whole new thing (which has no one label), in faith that we might bring a Linux-ish sensibility to it.

I am also encouraged that the Linux Foundation is already ahead of the curve with the Hyperledger Project (https://www.hyperledger.org): “an open source collaborative effort created to advance cross-industry blockchain technologies”. Those industries already include “leaders in finance, banking, Internet of Things, supply chains, manufacturing and Technology”.

The aspirations for new currencies, tokens, distributed ledgers and programming environments in this emerging mega-space are also in some ways similar to those of Linux, early on. Remember Linus' talk about “world domination” (catb.org/esr/writings/world-domination/world-domination-201.html) two decades before it came true? It's like that, without the Linus.

Both the internet and Linux were easy calls in the early 1990s, even if relatively few people called them. On the network side, closed “online services”, such as AOL and Compuserve, were their own best argument for a network of networks that supported everybody and favored nobody. So did the closed, isolated and doomed networks inside every large enterprise. On the operating system side, BSD was already proving itself as an open alternative to countless warring and closed UNIXes (and was busy forking into three different branches, helping open the way for Linux).

Now the one clear thing is that the internet's original promise of supporting everybody and favoring nobody is still under-fulfilled, meaning the opportunities are still vast, regardless of how much of life on the net is lived inside the feudal castles of what in Europe they call GAFA: Google, Amazon, Facebook and Apple.

In his blog post about Protocol Labs in May 2017 (https://www.usv.com/blog/protocol-labs), Brad Burnham wrote “all of us at Union Square Ventures (https://www.usv.com) believe in the decentralized, emergent, permissionless innovation that was so central to the vitality of the early internet.” He continued:

The key to mitigating the market power of the web giants is open protocols further up the stack (www.usv.com/blog/fat-protocols). If an open public communications network (the Internet) unlocked the distribution bottlenecks that characterized the media industry, an open public data layer is the key to unleashing another wave of innovation. It is the mission of Protocol Labs to coordinate the efforts of a large and passionate community of open source contributors to create these protocols.

It is an audacious mission. As you move higher in the stack the complexity of the protocols is exponentially greater. Luckily, they are not starting from scratch. Juan Benet, the founder of Protocol Labs, is the creator of IPFS (the Interplanetary File System: https://ipfs.io), an increasingly popular protocol that allows content on the web to be addressed directly instead of by reference to a file located on a specific server. This subtle but profound change means that a provably unique piece of content is no longer tied to a specific server but can exist anywhere there is a little surplus storage capacity on the web. Protocol Labs and everyone else working on open protocols today has another advantage that was not available to the creators of the original Internet protocols. They have blockchains.

Blockchain based crypto tokens have been described as the native business model of open source software (continuations.com/post/148098927445/crypto-tokens-and-the-coming-age-of-protocol). They have the promise of being able to fund the critical shared infrastructure of the information economy in a way that equity can not. Protocols are more valuable when they are open and shared broadly. But equity is most valuable if a company can extract monopoly profits from a resource they exclusively control. When a protocol incorporates an incentive in the form of a crypto token, it can resolve this inherent contradiction.

To start imagining where this goes, it may help to revisit Marshall McLuhan's framework for understanding the effects of a new technology in the world, which I wrote about in my May 2017 EOF (www.linuxjournal.com/content/will-anything-make-linux-obsolete). Every new medium (read: technology) has four sets of effects, he said, which can be best discovered in answers to four questions:

What does the medium enhance?

What does the medium make obsolete?

What does the medium retrieve that had been obsolesced earlier?

What does the medium reverse, or flip into, when pushed to extremes?

He also provided a graphical frame for the answers (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Marshall McLuhan's Framework

So, let's drop cryptocurrencies in the middle of that. My first Hmm says they—

Enhance exchange.

Retrieve the bazaar.

Obsolesce fiat currency.

Reverse into a Babel of mutually unintelligible currencies.

While distributed ledgers—

Enhance peer-to-peer.

Retrieve individual agency.

Obsolesce platform dominance.

Reverse into one-to-one.

Remember that this is a heuristic exercise, posed as questions to encourage many different answers. We need to ask these kinds of questions and keep revising our answers until the whole thing gets real.

I am sure the one real thing we already know is that protocols are causes and platforms are effects. Since platforms tend to be the most obvious effects, they also distract us from the boundless other things protocols cause.

Let's look at IPFS, for example. The Why page (https://ipfs.io/#why) at the IPFS site explains how it does for the web what HTTP cannot (or has not):

“HTTP is inefficient and inexpensive...with video delivery, a P2P approach could save 60% in bandwidth costs” (math.oregonstate.edu/~kovchegy/web/papers/p2p-vdn.pdf).

“Humanity's history is deleted daily...IPFS provides historic versioning (like git) and makes it simple to set up resilient networks for mirroring of data.”

“The web's centralization limits opportunity...IPFS remains true to the original vision of the open and flat web, but delivers the technology which makes that vision a reality.”

“Our apps are addicted to the backbone...IPFS powers the creation of diversely resilient networks which enable persistent availability with or without Internet backbone connectivity.”

And here's the list for How:

Each file and all of the blocks within it are given a unique fingerprint called a cryptographic hash. IPFS removes duplications across the network and tracks version history for every file. Each network node stores only content it is interested in and some indexing information that helps figure out who is storing what. When looking up files, you're asking the network to find nodes storing the content behind a unique hash. Every file can be found by human-readable names using a decentralized naming system called IPNS. And, of course, there's a white paper, by @JuanBenet (https://github.com/ipfs/papers/raw/master/ipfs-cap2pfs/ipfs-p2p-file-system.pdf).

It's time to re-distribute the Web, and countless other things built in the stack above the internet's original and still transcendent protocols. IPFS is one way. There are many others.

Let's make them happen.