The more things change, the more they stay the same. That may sound cliché, but it's still as true for the firmware that boots your operating system as it was in 2001 when Linux Journal first published Eric Biederman's "About LinuxBIOS". LinuxBoot is the latest incarnation of an idea that has persisted for around two decades now: use Linux as your bootstrap.

On most systems, firmware exists to put the hardware in a state where an operating system can take over. In some cases, the firmware and OS are closely intertwined and may even be the same binary; however, Linux-based systems generally have a firmware component that initializes hardware before loading the Linux kernel itself. This may include initialization of DRAM, storage and networking interfaces, as well as performing security-related functions prior to starting Linux. To provide some perspective, this pre-Linux setup could be done in 100 or so instructions in 1999; now it's more than a billion.

Oftentimes it's suggested that Linux itself should be placed at the boot vector. That was the first attempt at LinuxBIOS on x86, and it looked something like this:

#define LINUX_ADDR 0xfff00000; /* offset in memory-mapped NOR flash */

void linuxbios(void) {

void(*linux)(void) = (void *)LINUX_ADDR;

linux(); /* place this jump at reset vector (0xfffffff0) */

}

This didn't get very far though. Linux was not at the point where it could fully bootstrap itself—for example, it lacked functionality to initialize DRAM. So LinuxBIOS, later renamed coreboot, implemented the minimum hardware initialization functionality needed to start a kernel.

Today Linux is much more mature and can initialize much more—although not everything—on its own. A large part of this has to do with the need to integrate system and power management features, such as sleep states and CPU/device hotplug support, into the kernel for optimal performance and power-saving. Virtualization also has led to improvements in Linux's ability to boot itself.

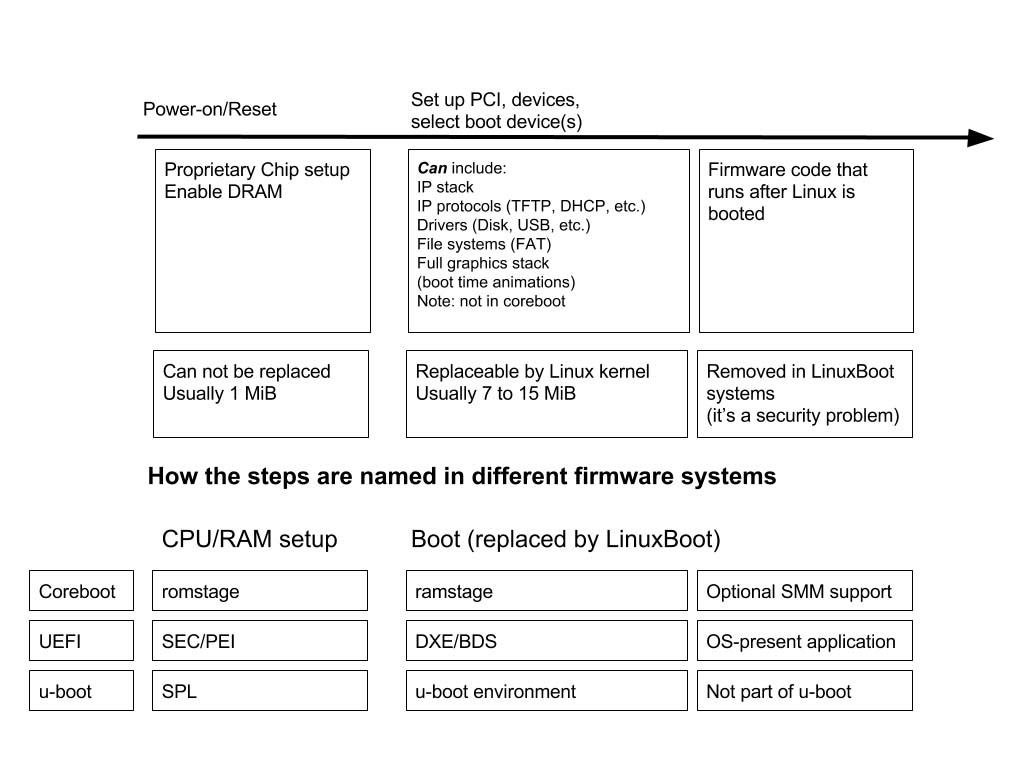

Modern firmware generally consists of two main parts: hardware initialization (early stages) and OS loading (late stages). These parts may be divided further depending on the implementation, but the overall flow is similar across boot firmware. The late stages have gained many capabilities over the years and often have an environment with drivers, utilities, a shell, a graphical menu (sometimes with 3D animations) and much more. Runtime components may remain resident and active after firmware exits. Firmware, which used to fit in an 8 KiB ROM, now contains an OS used to boot another OS and doesn't always stop running after the OS boots.

Figure 1. General Overview of Firmware Components and Boot Flow

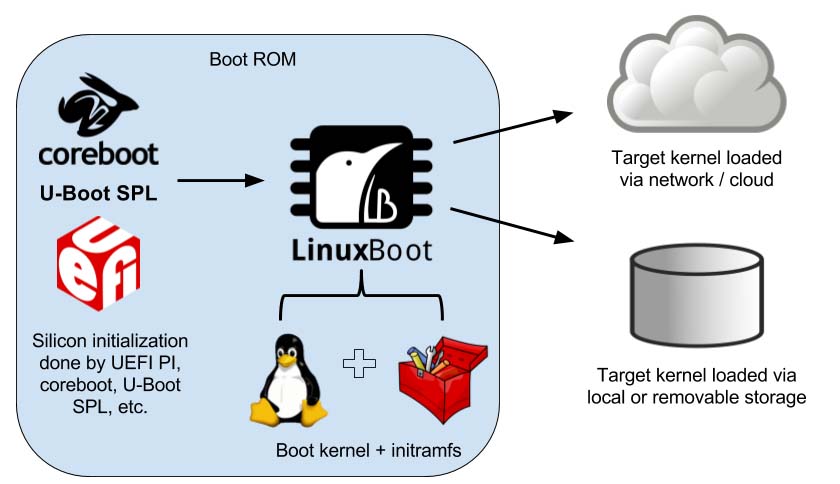

LinuxBoot replaces the late stages with a Linux kernel and initramfs, which are used to load and execute the next stage, whatever it may be and wherever it may come from. The Linux kernel included in LinuxBoot is called the "boot kernel" to distinguish it from the "target kernel" that is to be booted and may be something other than Linux.

Figure 2. LinuxBoot Components and Boot Flow

Bundling a Linux kernel with the firmware simplifies the firmware in two major ways. First, it eliminates the need for firmware to contain drivers for the ever-increasing variety of boot media, networking interfaces and peripherals. Second, we can use familiar tools from Linux userspace, such as wget and cryptsetup, to handle tasks like downloading a target OS kernel or accessing encrypted partitions, so that the late stages of firmware do not need to (re-)implement sophisticated tools and libraries.

For a system with UEFI firmware, all that is necessary is PEI (Pre-EFI Initialization) and a small number of DXE (Driver eXecution Environment) modules for things like SMM and ACPI table setup. With LinuxBoot, we don't need most DXE modules, as the peripheral initialization is done by Linux drivers. We also can skip the BDS (Boot Device Selection) phase, which usually contains a setup menu, a shell and various libraries necessary to load the OS. Similarly, coreboot's ramstage, which initializes various peripherals, can be greatly simplified or skipped.

In addition to the boot path, there are runtime components bundled with firmware that handle errors and other hardware events. These are referred to as RAS (Reliability, Availability and Serviceability) features. RAS features often are implemented as high-priority, highly privileged interrupt handlers that run outside the context of the operating system—for example, in system management mode (SMM) on x86. This brings performance and security concerns that LinuxBoot is addressing by moving some RAS features into Linux. For more information, see Ron Minnich's ECC'17 talk "Let's Move SMM out of firmware and into the kernel".

The initramfs used by the boot kernel can be any Linux-compatible environment that the user can fit into the boot ROM. For ideas, see "Custom Embedded Linux Distributions" published by Linux Journal in February 2018.

Some LinuxBoot developers also are working on u-root (u-root.tk), which is a universal rootfs written in Go. Go's portability and fast compilation make it possible to bundle the u-root initramfs as source packages with only a few toolchain binaries to build the environment on the fly. This enables real-time debugging on systems (for example, via serial console through a BMC) without the need to recompile or reflash the firmware. This is especially useful when a bug is encountered in the field or is difficult to reproduce.

While LinuxBoot can benefit those who are familiar with Linux and want more control over their boot flow, companies with large deployments of Linux-based servers or products stand to gain the most. They usually have teams of engineers or entire organizations with expertise in developing, deploying and supporting Linux kernel and userland—their business depends on it after all.

Replacing obscure and often closed firmware code with Linux enables organizations to leverage talent they already have to optimize their servers' and products' boot flow, maintenance and support functions across generations of hardware from potentially different vendors. LinuxBoot also enables them to be proactive instead of reactive when tracking and resolving boot-related issues.

LinuxBoot users gain transparency, auditability and reproducibility with boot code that has high levels of access to hardware resources and sets up platform security policies. This is more important than ever with well-funded and highly sophisticated hackers going to extraordinary lengths to penetrate infrastructure. Organizations must think beyond their firewalls and consider threats ranging from supply-chain attacks to weaknesses in hardware interfaces and protocol implementations that can result in privilege escalation or man-in-the-middle attacks.

Although not perfect, Linux offers robust, well-tested and well-maintained code that is mission-critical for many organizations. It is open and actively developed by a vast community ranging from individuals to multi-billion dollar companies. As such, it is extremely good at supporting new devices, the latest protocols and getting the latest security fixes.

LinuxBoot aims to do for firmware what Linux has done for the OS.

Although the idea of using Linux as its own bootloader is old and used across a broad range of devices, little has been done in terms of collaboration or project structure. Additionally, hardware comes preloaded with a full firmware stack that is often closed and proprietary, and the user might not have the expertise needed to modify it.

LinuxBoot is changing this. The last missing parts are actively being worked out to provide a complete, production-ready boot solution for new platforms. Tools also are being developed to reorganize standard UEFI images so that existing platforms can be retrofitted. And although the current efforts are geared toward Linux as the target OS, LinuxBoot has potential to boot other OS targets and give those users the same advantages mentioned earlier. LinuxBoot currently uses kexec and, thus, can boot any ELF or multiboot image, and support for other types can be added in the future.

Contributors include engineers from Google, Horizon Computing Solutions, Two Sigma Investments, Facebook, 9elements GmbH and more. They are currently forming a cohesive project structure to promote LinuxBoot development and adoption. In January 2018, LinuxBoot became an official project within the Linux Foundation with a technical steering committee composed of members committed to its long-term success. Effort is also underway to include LinuxBoot as a component of Open Compute Project's Open System Firmware project. The OCP hardware community launched this project to ensure cloud hardware has a secure, open and optimized boot flow that meets the evolving needs of cloud providers.

LinuxBoot leverages the capabilities and momentum of Linux to open up firmware, enabling developers from a variety of backgrounds to improve it whether they are experts in hardware bring-up, kernel development, tooling, systems integration, security or networking. To join us, visit linuxboot.org.

—David Hendricks, Ron Minnich, Chris Koch and Andrea Barberio