In this two-part series, I introduce this now-trending technology, describe how it works and provide instructions for deploying your very own private blockchain network.

The concept of cryptocurrency isn't anything new, although with the prevalence of the headlines alluded to above, one might think otherwise. Invented and released in 2009 by an unknown party under the name Satoshi Nakamoto, bitcoin is one such kind of cryptocurrency in that it provides a decentralized method for engaging in digital transactions. It is also a global technology, which is a fancy way of saying that it's a worldwide payment system. With the technology being decentralized, not one single entity is considered to have ownership or the ability to impose regulations on the technology.

But, what does that truly mean? Transactions are secure. This makes them more difficult to track and, therefore, difficult to tax. This is because these transactions are strictly peer-to-peer, without an intermediary in between. Sounds too good to be true, right? Well, it is that good.

Although transactions are limited to the two parties involved, they do, however, need to be validated across a network of independently functioning nodes, called a blockchain. Using cryptography and a distributed public ledger, transactions are verified.

Now, aside from making secure and more-difficult-to-trace transactions, what is the real appeal to these cryptocurrency platforms? In the case of bitcoin, a "bitcoin" is generated as a reward through the process of "mining". And if you fast-forward to the present, bitcoin has earned monetary value in that it can be used to purchase both goods and services, worldwide. Remember, this is a digital currency, which means no physical "coins" exist. You must keep and maintain your own cryptocurrency wallet and spend the money accrued with retailers and service providers that accept bitcoin (or any other type of cryptocurrency) as a method of payment.

All hype aside, predicting the price of cryptocurrency is a fool's errand, and there's not a single variable driving its worth. One thing to note, however, is that cryptocurrency is not in any way a monetary investment in a real currency. Instead, buying into cryptocurrency is an investment into a possible future where it can be exchanged for goods and services—and that future may be arriving sooner than expected.

Now, this doesn't mean cryptocurrency has no cash value. In fact, it does. As of the day I am writing this (January 27, 2018), a single bitcoin is $11,368.56 USD. This value is extremely volatile, and who knows what direction it will take tomorrow. One thing influencing the value of a bitcoin is the rate of adoption. More people using the technology results in more transactions being verified by the people-owned nodes forming the underlying blockchain. In turn, the owners of the verification systems earn their rewards, thereby increasing the value of the technology. It's simple: verify more transactions, and earn more money. Sure, there is a bit more to it, but that's the general idea.

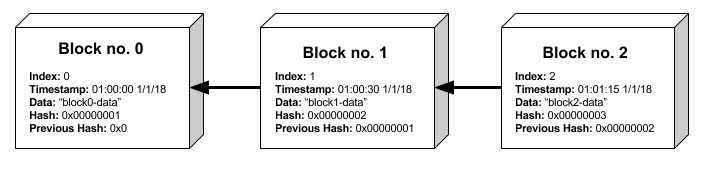

The owners of the verification systems are referred to as "miners". Miners provide a service of record keeping. Such a service requires a good amount of processing power to handle the cryptographic computations. The purpose of the miner is to keep the underlying blockchain consistent, complete and unaltered. A miner repeatedly verifies and collects broadcasted transactions into groups of transactions referred to as blocks. Using an SHA-256 algorithm (Secure Hash Algorithm 256-bit hash), each new block contains a cryptographic hash of the block prior to it, establishing a link for forming the chain of blocks, hence the name, blockchain.

Figure 1. An Example of How Blocks of Data Are "Chained" to One Anotherl

With the rise of cryptocurrency and the rise of miners competing to earn their fair share of the digital currency, we are now facing a dilemma—a global shortage of high-end PC graphics adapters. Even previously used adapters are resold at a much higher price than newly boxed versions. But why is that? Using such high-end cards with enough onboard memory and dedicated processing capabilities easily can yield several dollars in cryptocurrency per day. Remember, mining requires the processing of memory-hungry algorithms. And as cryptocurrency prices continue to increase, albeit at a rapid rate, the value of the digital currency awarded to miners also increases. This shortage of graphics adapters has become an increasing bottleneck for existing miners looking to expand their operations or for new miners to get in on the action. Hopefully, graphic card vendors will address this shortage sooner rather than later.

Multiple platforms exist for crypto-trading. You may come across articles discussing bitcoin and comparing that currency to others like ethereum or litecoin. Initially, those articles can lead to confusion between the two different types of digital coins: 1) cryptocurrencies and 2) tokens. The key things to remember are the following:

A bitcoin or litecoin or any other form of cryptocurrency actively competes against existing money and gold in the hopes of replacing them as an accepted form of global currency. As mentioned previously, the technology promises a non-regulated and globally accessible currency—one that contains the same stable value regardless of location. This concept definitely could appeal to those living in unstable countries with unstable currencies.

And ethereum? Well, it deals in tokens. It works on the idea of contracts. Ethereum is a platform that allows its users to write conditional digital "smart contracts", showing proof of a transaction that never can be deleted.

In the modern world, a traditionally written contract will outline the terms of a relationship, usually enforceable by law. A smart contract will enforce a relationship using cryptographic code—that is, by executing the conditions defined by its creators using a program. What makes ethereum more interesting is that unlike bitcoin (or litecoin for that matter), the platform does not limit itself to the currency use case.

Much like bitcoin, when a transaction takes place utilizing one or more of these contracts, transaction fees are charged to source the computation power required. The more computational power needed, the higher the fee.

To understand this cryptocurrency phenomenon and its explosive growth in popularity, you need to understand the technology supporting it: the blockchain. As mentioned previously, a blockchain consists of a continuously growing list of records captured in the form of blocks. Using cryptography, each new block is linked and secured to an existing chain of blocks.

Each block will contain a hash pointer to the previous block within the chain, a timestamp and transactional data. By design, the blockchain is resistant to any sort of modification of data. This is because a blockchain provides an open and distributed ledger to record transactions between two interested parties efficiently, reliably and permanently.

Once data has been recorded, the data in a given block cannot be altered without altering all subsequent blocks.

I guess you can think of this as a distributed "database" where its contents are duplicated hundreds, if not thousands, of times across a network of computers. This method of replication emphasizes the decentralized aspect of the technology. Without a centralized version or a single "master" copy, this database is public and, therefore, can be verified easily without risk or fear of hacking or corruption. Simultaneously hosted by millions of computing nodes, the contents of this database are accessible to anyone on the internet. As an added benefit, the distributed and decentralized model reassures its users that no single point of failure exists. Imagine that one or more of these computing nodes are either inaccessible or experiencing some sort of internal failures or are even producing corrupted data. The blockchain is resilient in that it will continue to make available the requested data contents and in their proper (that is, uncorrupted) format. This is because of a technique commonly referred to as the Byzantine Fault Tolerance method.

Systems fail, and they can fail for multiple reasons (such as hardware, software, power, networking connectivity and others). This is a fact. Also, not all failures are easily detectable (even through traditional fault-tolerance mechanisms) nor will they always appear the same to the rest of the systems in the networked cluster. Again, imagine a large network consisting of hundreds, if not thousands, of nodes. To handle such unpredictable conditions, one must employ a voting system to ensure that the cluster will tolerate the failure or misbehavior.

A Byzantine fault is defined by any fault showcasing different types of symptoms to different observers (that is, distributed computing systems). A Byzantine failure is the loss of a system service due to a Byzantine fault in an environment where a consensus must reached in order to perform that one service or operation.

The purpose of Byzantine Fault Tolerance (BFT) is to defend the distributed platform against such Byzantine failures. Failing components of the system will not prevent the remaining components from reaching an agreement among themselves, where such an agreement is required to perform an operation. Correctly functioning components of a BFT system will continue to provide uninterrupted service, assuming that not too many faults exist.

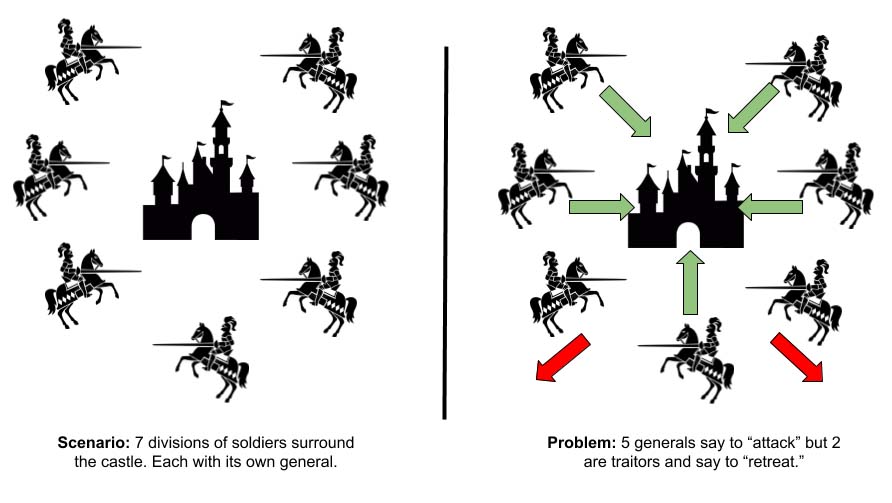

The name of this mechanism is derived from the Byzantine Generals' Problem (BGP). The BGP highlights an agreement problem, where there is a disagreement with all participating members. Imagine a scenario where several divisions of the Byzantine army are camped outside a fortified city. Each division has its own general, and the only way the generals are able to communicate with each other is through the use of messengers. The generals need to decide on a common plan of action. The problem is, some of the generals may and very well could be traitors. With one traitor in their midst, can the non-traitors decide on a common plan?

In a BFT environment, the answer to this question is yes. In a group of three, one traitor makes it impossible not to reach a majority consensus. For instance, if one general says "attack" while the other two say to "retreat", it is easy to determine who the traitor of the group is. It is also possible to reach some sort of agreement across the non-traitors. Now, apply this concept to a distributed network of computing nodes. For example, when f number of nodes go Byzantine, 2f + 1 nodes will not tolerate the misbehavior. All you need is 1 properly functioning node more than the potentially faulty nodes.

Figure 2. The Byzantine Generals' Problem Illustrated

Now, why am I talking about this? The BFT is at the core of a blockchain's resiliency. If a consensus cannot be made to handle a transaction, the blockchain itself is no good.

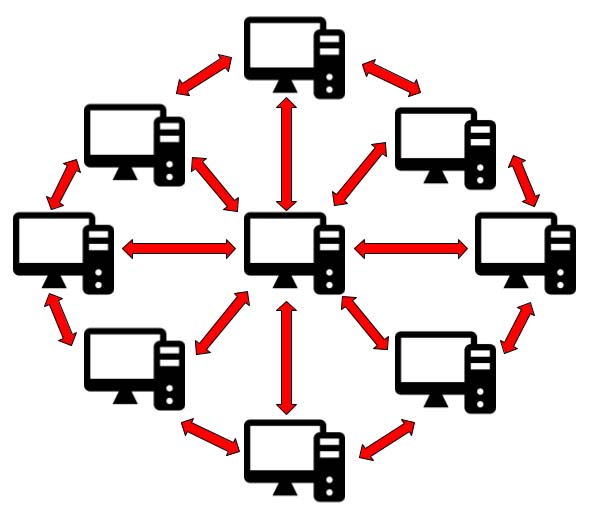

A network consisting of computing nodes is what makes up the blockchain. A node gets an identical copy of the blockchain as soon as it joins the network. Each node is considered to be an administrator of the blockchain and not in any more control over the other nodes within the cluster—again, the result of being decentralized.

Figure 3. An Example of a Decentralized Blockchain Network

This method of computing is what lends the blockchain its robustness. Aside from updating the blockchain, each node can and will act independently from the other regardless of how it was accessed. And when it needs to append a new block to the chain, it will broadcast the update to the rest of the nodes (updating the public ledger).

Whatever the user-driven event, it is considered to be a function of the network as a whole. It is the global network that manages the application, and it will operate on a user-to-user or peer-to-peer basis. Each node, when accessed independently, is tasked with confirming the requested transaction (such as mining). Already alluded to previously, it is this core concept that makes the blockchain that much more secure. The blockchain technology eliminates the risks (and vulnerabilities) introduced with data being held (or managed) centrally and not replicated across the network. Another way to think of it is this: instead of having a single entity validate the transaction, you now have multiple entities validating the transaction after reaching a consensus. They act as witnesses, and not one single entity has more authority over the other. This leaves no room for ambiguity, and if one or more nodes misrepresents the original data, the BFT model will address that.

Almost everyone reading this is familiar with the constant security problems running rampant on the internet. We personally attempt to protect both our identity and our assets online by relying on the traditional "user name" and "password" systems. Blockchain takes this a step further and differs in that its security stems from its use of encryption technologies. The authentication "problem" is solved with the generation of "keys". A user will create a public key (a long and randomly generated numeric string) and a private key (which acts like a password). The public key serves as the user's address within the blockchain, and any transaction involving that address will be recorded as belonging to that address. The private key gives its owner access to his or her digital assets. The combination of both public and private keys provides a digital signature. The only concern here is taking the appropriate measures to protect private keys.

By now, you should have more of a complete picture of how all of these components tie together.

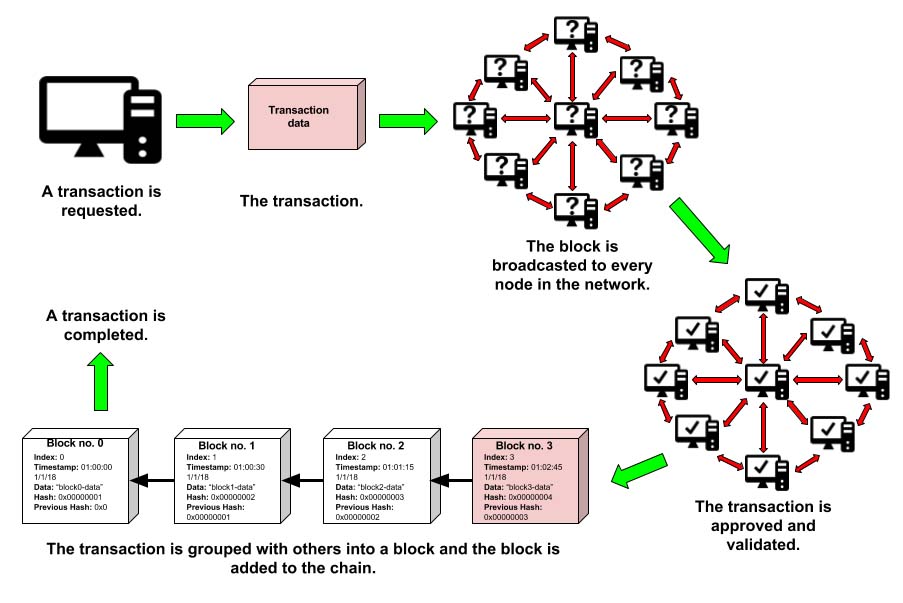

Figure 4. The General Handling of a Transaction across a Blockchain Network

For example, let's say there's a bitcoin transaction (or it could be something else entirely different), but imagine someone in the network is requesting the transaction. This requested transaction is then broadcasted across a peer-to-peer network of computing nodes. Using cryptographic algorithms, the network of nodes validates the user's status and the transaction. Once verified, the transaction is combined with other transactions, creating a new block of data for the public ledger. The new block of data is then appended to the existing blockchain and is done in a way that makes it permanent and unalterable. Then the transaction is complete. Using timestamping schemes, all transactions are serialized.

Much like TCP/IP, the blockchain is a foundation technology. As TCP/IP enabled the internet by the 1990s, you can expect wonderful new beginnings with the blockchain. It is still a bit too early to see how it will evolve. This revolutionary technology has enabled organizations to explore what it can and will mean for their businesses. Many of these same organizations already have begun the exploration, although it primarily has been focused around financial services. The possibilities are enormous, and it seems that any industry dealing with any sort of transaction-based model will be disrupted by the technology.

This article covers the rise and interest in cryptocurrencies and begins to dive into the underlying blockchain technology that enables it. In the next part of this series, using open-source tools, I start to describe how to build your very own private blockchain network. This private deployment will allow you to dig deeper into the details highlighted here. The technology may be centered around cryptocurrency today, but I also look at various industries the blockchain can help to redefine and the potential for a promising future leveraging the technology.

Petros Koutoupis, LJ Contributing Editor, is currently a senior platform architect at IBM for its Cloud Object Storage division (formerly Cleversafe). He is also the creator and maintainer of the RapidDisk Project. Petros has worked in the data storage industry for well over a decade and has helped pioneer the many technologies unleashed in the wild today.