curses functions to read the keyboard and manipulate the screen. By Jim HallMy previous article introduced the ncurses library and provided a simple program that demonstrated a few curses functions to put text on the screen. In this follow-up article, I illustrate how to use a few other curses functions.

When I was growing up, my family had an Apple II computer. It was on this machine that my brother and I taught ourselves how to write programs in AppleSoft BASIC. After writing a few math puzzles, I moved on to creating games. Having grown up in the 1980s, I already was a fan of the Dungeons and Dragons tabletop games, where you role-played as a fighter or wizard on some quest to defeat monsters and plunder loot in strange lands. So it shouldn't be surprising that I also created a rudimentary adventure game.

The AppleSoft BASIC programming environment supported a neat feature: in standard resolution graphics mode (GR mode), you could probe the color of a particular pixel on the screen. This allowed a shortcut to create an adventure game. Rather than create and update an in-memory map that was transferred to the screen periodically, I could rely on GR mode to maintain the map for me, and my program could query the screen as the player's character moved around the screen. Using this method, I let the computer do most of the hard work. Thus, my top-down adventure game used blocky GR mode graphics to represent my game map.

My adventure game used a simple map that represented a large field with a mountain range running down the middle and a large lake on the upper-left side. I might crudely draw this map for a tabletop gaming campaign to include a narrow path through the mountains, allowing the player to pass to the far side.

Figure 1. A simple Tabletop Game Map with a Lake and Mountains

You can draw this map in curses using characters to represent grass, mountains and water. Next, I describe how to do just that using curses functions and how to create and play a similar adventure game in the Linux terminal.

In my last article, I mentioned that most curses programs start with the same set of instructions to determine the terminal type and set up the curses environment:

initscr();

cbreak();

noecho();

For this program, I add another statement:

keypad(stdscr, TRUE);

The TRUE flag allows curses to read the keypad and function keys from the user's terminal. If you want to use the up, down, left and right arrow keys in your program, you need to use keypad(stdscr, TRUE) here.

Having done that, you now can start drawing to the terminal screen. The curses functions include several ways to draw text on the screen. In my previous article, I demonstrated the addch() and addstr() functions and their associated mvaddch() and mvaddstr() counterparts that first moved to a specific location on the screen before adding text. To create the adventure game map on the terminal, you can use another set of functions: vline() and hline(), and their partner functions mvvline() and mvhline(). These mv functions accept screen coordinates, a character to draw and how many times to repeat that character. For example, mvhline(1, 2, '-', 20) will draw a line of 20 dashes starting at line 1, column 2.

To draw the map to the terminal screen programmatically, let's define this draw_map() function:

#define GRASS ' '

#define EMPTY '.'

#define WATER '~'

#define MOUNTAIN '^'

#define PLAYER '*'

void draw_map(void)

{

int y, x;

/* draw the quest map */

/* background */

for (y = 0; y < LINES; y++) {

mvhline(y, 0, GRASS, COLS);

}

/* mountains, and mountain path */

for (x = COLS / 2; x < COLS * 3 / 4; x++) {

mvvline(0, x, MOUNTAIN, LINES);

}

mvhline(LINES / 4, 0, GRASS, COLS);

/* lake */

for (y = 1; y < LINES / 2; y++) {

mvhline(y, 1, WATER, COLS / 3);

}

}

In drawing this map, note the use of mvvline() and mvhline() to fill large chunks of characters on the screen. I created the fields of grass by drawing horizontal lines (mvhline) of characters starting at column 0, for the entire height and width of the screen. I added the mountains on top of that by drawing vertical lines (mvvline), starting at row 0, and a mountain path by drawing a single horizontal line (mvhline). And, I created the lake by drawing a series of short horizontal lines (mvhline). It may seem inefficient to draw overlapping rectangles in this way, but remember that curses doesn't actually update the screen until I call the refresh() function later.

Having drawn the map, all that remains to create the game is to enter a loop where the program waits for the user to press one of the up, down, left or right direction keys and then moves a player icon appropriately. If the space the player wants to move into is unoccupied, it allows the player to go there.

You can use curses as a shortcut. Rather than having to instantiate a version of the map in the program and replicate this map to the screen, you can let the screen keep track of everything for you. The inch() function and associated mvinch() function allow you to probe the contents of the screen. This allows you to query curses to find out whether the space the player wants to move into is already filled with water or blocked by mountains. To do this, you'll need a helper function that you'll use later:

int is_move_okay(int y, int x)

{

int testch;

/* return true if the space is okay to move into */

testch = mvinch(y, x);

return ((testch == GRASS) || (testch == EMPTY));

}

As you can see, this function probes the location at column y, row x and returns true if the space is suitably unoccupied, or false if not.

That makes it really easy to write a navigation loop: get a key from the keyboard and move the user's character around depending on the up, down, left and right arrow keys. Here's a simplified version of that loop:

do {

ch = getch();

/* test inputted key and determine direction */

switch (ch) {

case KEY_UP:

if ((y > 0) && is_move_okay(y - 1, x)) {

y = y - 1;

}

break;

case KEY_DOWN:

if ((y < LINES - 1) && is_move_okay(y + 1, x)) {

y = y + 1;

}

break;

case KEY_LEFT:

if ((x > 0) && is_move_okay(y, x - 1)) {

x = x - 1;

}

break;

case KEY_RIGHT

if ((x < COLS - 1) && is_move_okay(y, x + 1)) {

x = x + 1;

}

break;

}

}

while (1);

To use this in a game, you'll need to add some code inside the loop to allow other keys (for example, the traditional WASD movement keys), provide a method for the user to quit the game and move the player's character around the screen. Here's the program in full:

/* quest.c */

#include <curses.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#define GRASS ' '

#define EMPTY '.'

#define WATER '~'

#define MOUNTAIN '^'

#define PLAYER '*'

int is_move_okay(int y, int x);

void draw_map(void);

int main(void)

{

int y, x;

int ch;

/* initialize curses */

initscr();

keypad(stdscr, TRUE);

cbreak();

noecho();

clear();

/* initialize the quest map */

draw_map();

/* start player at lower-left */

y = LINES - 1;

x = 0;

do {

/* by default, you get a blinking cursor - use it to indicate

* player */

mvaddch(y, x, PLAYER);

move(y, x);

refresh();

ch = getch();

/* test inputted key and determine direction */

switch (ch) {

case KEY_UP:

case 'w':

case 'W':

if ((y > 0) && is_move_okay(y - 1, x)) {

mvaddch(y, x, EMPTY);

y = y - 1;

}

break;

case KEY_DOWN:

case 's':

case 'S':

if ((y < LINES - 1) && is_move_okay(y + 1, x)) {

mvaddch(y, x, EMPTY);

y = y + 1;

}

break;

case KEY_LEFT:

case 'a':

case 'A':

if ((x > 0) && is_move_okay(y, x - 1)) {

mvaddch(y, x, EMPTY);

x = x - 1;

}

break;

case KEY_RIGHT:

case 'd':

case 'D':

if ((x < COLS - 1) && is_move_okay(y, x + 1)) {

mvaddch(y, x, EMPTY);

x = x + 1;

}

break;

}

}

while ((ch != 'q') && (ch != 'Q'));

endwin();

exit(0);

}

int is_move_okay(int y, int x)

{

int testch;

/* return true if the space is okay to move into */

testch = mvinch(y, x);

return ((testch == GRASS) || (testch == EMPTY));

}

void draw_map(void)

{

int y, x;

/* draw the quest map */

/* background */

for (y = 0; y < LINES; y++) {

mvhline(y, 0, GRASS, COLS);

}

/* mountains, and mountain path */

for (x = COLS / 2; x < COLS * 3 / 4; x++) {

mvvline(0, x, MOUNTAIN, LINES);

}

mvhline(LINES / 4, 0, GRASS, COLS);

/* lake */

for (y = 1; y < LINES / 2; y++) {

mvhline(y, 1, WATER, COLS / 3);

}

}

In the full program listing, you can see the complete arrangement of curses functions to create the game:

1) Initialize the curses environment.

2) Draw the map.

3) Initialize the player coordinates (lower-left).

4) Loop:

5) When done, close the curses environment and exit.

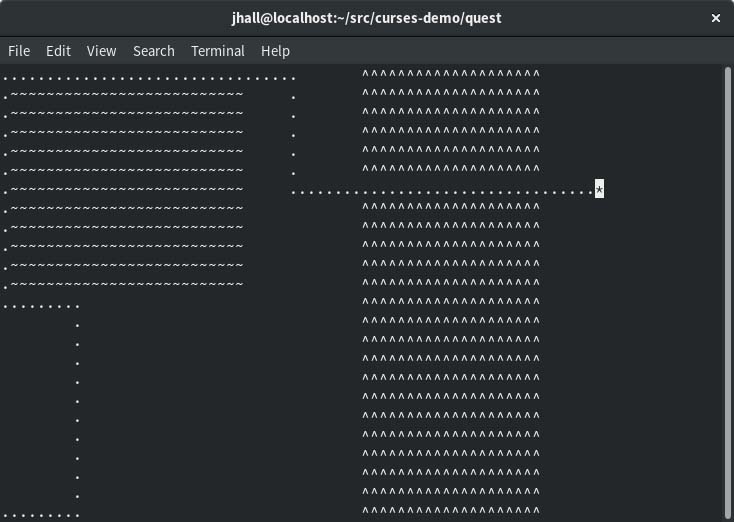

When you run the game, the player's character starts in the lower-left corner. As the player moves around the play area, the program creates a "trail" of dots. This helps show where the player has been before, so the player can avoid crossing the path unnecessarily.

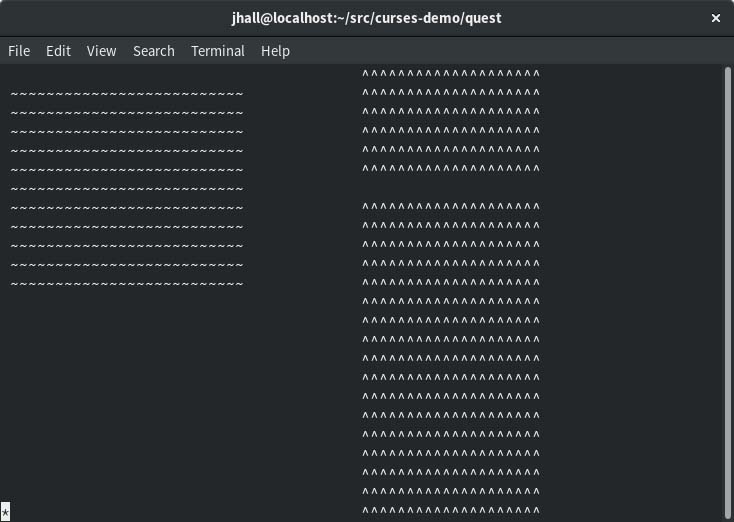

Figure 2. The player starts the game in the lower-left corner.

Figure 3. The player can move around the play area, such as around the lake and through the mountain pass.

To create a complete adventure game on top of this, you might add random encounters with various monsters as the player navigates his or her character around the play area. You also could include special items the player could discover or loot after defeating enemies, which would enhance the player's abilities further.

But to start, this is a good program for demonstrating how to use the curses functions to read the keyboard and manipulate the screen.

This program is a simple example of how to use the curses functions to update and read the screen and keyboard. You can do so much more with curses, depending on what you need your program to do. In a follow up article, I plan to show how to update this sample program to use colors. In the meantime, if you are interested in learning more about curses, I encourage you to read Pradeep Padala's NCURSES Programming HOWTO at the Linux Documentation Project.

Jim Hall is an advocate for free and open-source software, best known for his work on the FreeDOS Project, and he also focuses on the usability of open-source software. Jim is the Chief Information Officer at Ramsey County, Minn.