Back in the mists of antiquity when I started reading Linux Journal, figuring out what an infrastructure was going to cost was (although still obnoxious in some ways) straightforward. You'd sign leases with colocation providers, buy hardware that you'd depreciate on a schedule and strike a deal in blood with a bandwidth provider, and you were more or less set until something significant happened to your scale.

In today's brave new cloud world, all of that goes out the window. The public cloud providers give with one hand ("Have a full copy of any environment you want, paid by the hour!"), while taking with the other ("A single Linux instance will cost you $X per hour, $Y per GB transferred per month, and $Z for the attached storage; we simplify this pricing into what we like to call 'We Make It Up As We Go Along'").

In my day job, I'm a consultant who focuses purely on analyzing and reducing the Amazon Web Services (AWS) bill. As a result, I've seen a lot of environments doing different things: cloud-native shops spinning things up without governance, large enterprises transitioning into the public cloud with legacy applications that don't exactly support that model without some serious tweaking, and cloud migration projects that somehow lost their way severely enough that they were declared acceptable as they were, and the "multi-cloud" label was slapped on to them. Throughout all of this, some themes definitely have emerged that I find that people don't intuitively grasp at first. To wit:

It's relatively straightforward to do the basic arithmetic to figure out what a current data center would cost to put into the cloud as is—generally it's a lot! If you do a 1:1 mapping of your existing data center into the cloudy equivalents, it invariably will cost more; that's a given. The real cost savings arise when you start to take advantage of cloud capabilities—your web server farm doesn't need to have 50 instances at all times. If that's your burst load, maybe you can scale that in when traffic is low to five instances or so? Only once you fall into a pattern (and your applications support it!) of paying only for what you need when you need it do the cost savings of cloud become apparent.

One of the most misunderstood aspects of Cloud Economics is the proper calculation of Total Cost of Ownership, or TCO. If you want to do a break-even analysis on whether it makes sense to build out a storage system instead of using S3, you've got to include a lot more than just a pile of disks. You've got to factor in disaster recovery equipment and location, software to handle replication of data, staff to run the data center/replace drives, the bandwidth to get to the storage from where it's needed, the capacity planning for future growth—and the opportunity cost of building that out instead of focusing on product features.

It's easy to get lost in the byzantine world of cloud billing dimensions and lose sight of the fact that you've got staffing expenses. I've yet to see a company with more than five employees wherein the cloud expense wasn't dwarfed by payroll. Unlike the toy projects some of us do as labors of love, engineering time costs a lot of money. Retraining existing staff to embrace a cloud future takes time, and not everyone takes to this new paradigm quickly.

Accounting is going to have to weigh in on this, and if you're not prepared for that conversation, it's likely to be unpleasant. You're going from an old world where you could plan your computing expenses a few years out and be pretty close to accurate. Cloud replaces that with a host of variables to account for, including variable costs depending upon load, amortization of Reserved Instances, provider price cuts and a complete lack of transparency with regard to where the money is actually going (Dev or Prod? Which product? Which team spun that up? An engineer left the company six months ago, but 500TB of that person's data is still sitting there, and so on).

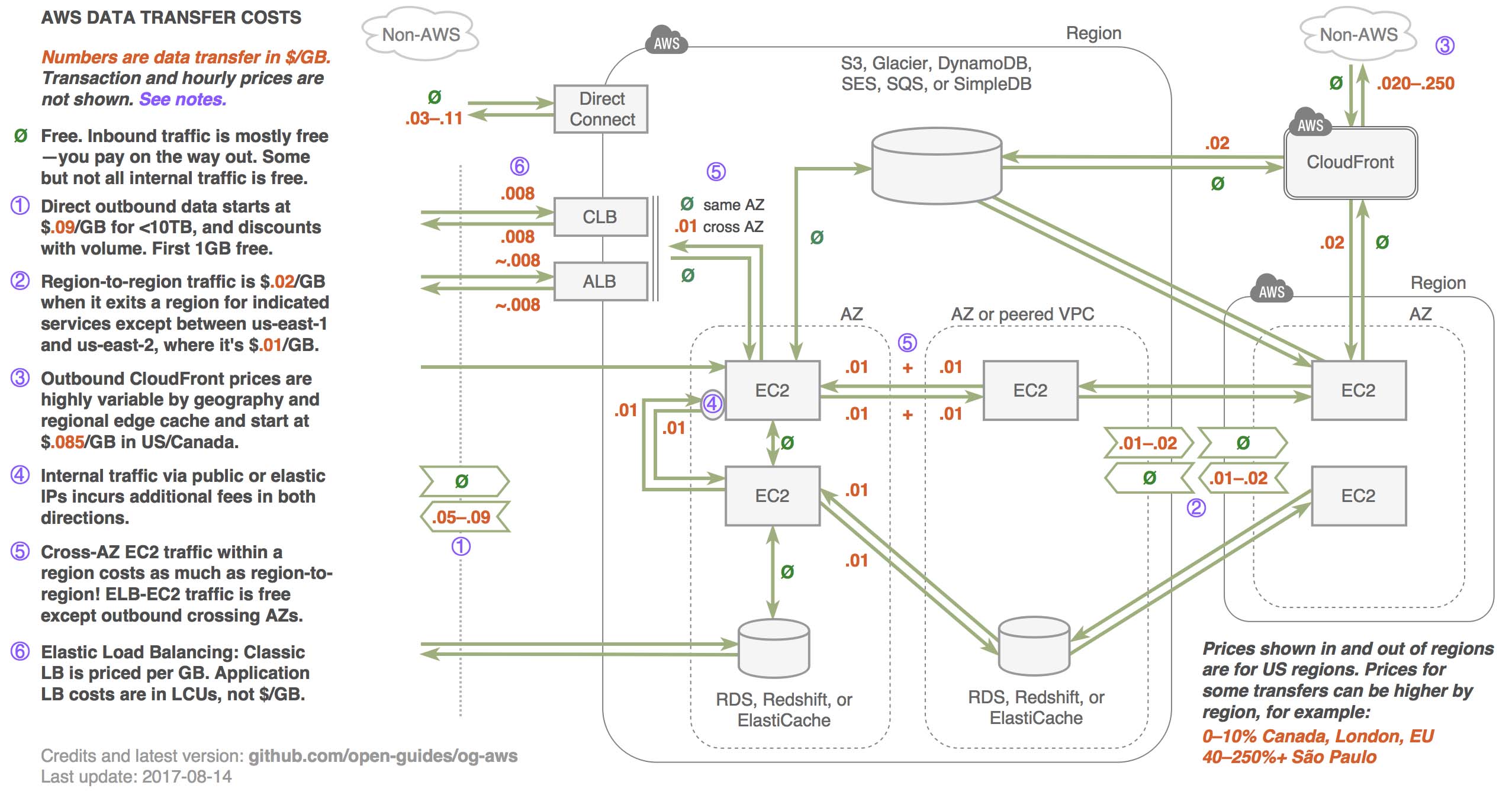

The worst part is that all of this isn't apparent to newcomers to cloud billing, so when you trip over these edge cases, it's natural to feel as if the problem is somehow your fault. I do this for a living, and I was stymied trying to figure out what data transfer was likely to cost in AWS. I started drawing out how it's billed to customers, and ultimately came up with the "AWS Data Transfer Costs" diagram shown in Figure 1.

Figure 2. A convoluted mapping of how AWS data transfer is priced out.

If you can memorize those figures, you're better at this than I am by a landslide! It isn't straightforward, it's not simple, and it's certainly not your fault if you don't somehow intrinsically know these things.

That said, help is at hand. AWS billing is getting much more understandable, with the advent of such things as free Reserved Instance recommendations, the release of the Cost Explorer API and the rise of serverless technologies. For their part, Google's GCP and Microsoft's Azure learned from the early billing stumbles of AWS, and as a result, both have much more understandable cost structures. Additionally, there are a host of cost visibility Platform-as-a-Service offerings out there; they all do more or less the same things as one another, but they're great for ad-hoc queries around your bill. If you'd rather build something you can control yourself, you can shove your billing information from all providers into an SQL database and run something like QuickSight or Tableau on top of it to aide visualization, as many shops do today.

In return for this ridiculous pile of complexity, you get something rather special—the ability to spin up resources on-demand, for as little time as you need them, and pay only for the things that you use. It's incredible as a learning resource alone—imagine how much simpler it would have been in the late 1990s to receive a working Linux VM instead of having to struggle with Slackware's installation for the better part of a week. The cloud takes away, but it also gives.

Corey Quinn is currently a Cloud Economist at the Quinn Advisory Group, and an advisor to ReactiveOps. Corey has a history as an engineering director, public speaker and cloud architect. He specializes in helping companies address horrifying AWS bills, and curates LastWeekinAWS.com, a weekly newsletter summarizing the latest in AWS news, blogs and tips, sprinkled with snark.