In today's software business, getting solid code out the door fast is a must, and practices to make that easier are part of any organization's DevOps toolset. Git has risen to the top of the heap of version control tools, because it's simple, fast and makes collaboration easy.

For developers, tools like Git ensure that their code isn't just backed up and made available to others, but nearly guarantees that it can be incorporated into a wide variety of third-party development tools—from Jenkins to Visual Studio—that make continuous integration and continuous delivery (CI/CD) possible. Orchestration, automation and deployment tools easily integrate with Git as well, which means code developed on any laptop or workstation anywhere can be merged, branched and integrated into deployed software. That's why version control repositories are the future of software development and DevOps, no matter how big or small you are, and no matter whether you're building monolithic apps or containerized ones.

Git works by taking snapshots of code on every commit, so every version of contributed code is always available. That means it's easy to roll back changes or look over different contributors' work.

If you're working in an environment that uses Git, you can do your work even when you're offline. Everything is saved in a project structure on your workstation, just as it is in the remote Git repository, and when you're next online, your commits and pushes update the master (or other) code branch quickly and easily.

Most Git users (even newbies) use the Git command-line tools to clone, commit and push changes, because it's easy, and for nearly 28-million developers, GitHub has become the de facto remote Git-based repository for their work. In fact, GitHub has moved beyond being just a code repository to become a multifaceted code community featuring 85-million projects. That's a lot of code.

GitLab is gaining popularity as a remote code repository too, but it's smaller and bills itself as more DevOps-focused, with CI/CD tool included for free. Both repositories offer free hosted accounts that allow users to create a namespace, and start contributing and collaborating right away. The graphical browser interfaces offered by the GitHub- and GitLab-hosted services make it easy to manage projects and project code, and also to add SSH keys, so you easily can connect from your remote terminal on Linux, Windows or Mac.

To become familiar with how Git works, install the latest package on your workstation, sign up for a free account on GitHub or GitLab and start experimenting:

$ sudo apt install git

If you're a GitHub pro, you can speed ahead and start thinking about a couple projects you have that you'd like to import into GitLab. That'll give you a bit of a head start when you're ready to start building out your on-premises GitLab deployment.

With Git at their core, GitHub and GitLab have more in common than not, although GitLab is more generous with private repositories for its free version. The folks over at UserSnap did a nice job of summarizing the differences in a recent post. Check the Resources section at the end of this article to learn more.

For this how-to, you'll be deploying GitLab CE omnibus, a full-featured and free version of GitLab. If you've used the free online version at GitLab.com, it will look familiar to you. If you've used only GitHub and want to get a taste for GitLab CE before you deploy it locally, try the online version of GitLab to get a feel for the differences.

One more thing to think about if you're considering doing a full migration away from GitHub: check to see how any third-party apps you use integrate with GitLab. Since it's all Git under the covers, chances are good that GitLab will integrate as easily as GitHub, but it doesn't hurt to check. If you still have doubts, check the Resources section for GitLab's application integration list.

This tutorial is about deploying GitLab CE on-premises, but in this day and age, there's certainly more than one way to do that. For example, you can install GitLab on a fresh Linux VM of your choice, which is what I describe in this how-two, but you also can deploy it from a ready-made virtual machine .ova, a Turnkey template, an official Docker image or from a Helm repository for Kubernetes. If "in-house" means the public cloud for you, GitLab also offers options for AWS, Azure, Google Cloud Platform and Mesosphere deployments.

And, in case that's not enough, there also are ways to automate the deployment using tools like Ansible, Chef, Puppet, Juju, Vagrant and more. For this tutorial, I describe deploying on an Ubuntu 16.04 VM, but most of the instructions easily can be adapted to Debian, CentOS, OpenSUSE and even Raspbian for the RPi. GitLab offers specific instructions for most modern flavors of Linux, including the Raspberry Pi.

Before you begin your GitLab deployment, put some thought into how you'll use it. If you're noodling around in a home lab, you easily can get by with a relatively small VM with modest storage. If you're looking at something a little more robust, give some thought to drive capacity and DNS. GitLab stores information in a database and does it efficiently, but if you're going to have hundreds of developers and hundreds of projects, think about how the underlying database will grow over time.

If you're deploying into a production setting, it goes without saying that you need to build in some sort of disaster recovery and business continuity capabilities. After all, this is a standalone deployment. If you're planning something really big, treat it as you would any core service that needs protecting.

With that said, GitLab doesn't take many resources to run, and it can be readily scaled to 32,000 users on a single application server.

GitLab recommends system requirements based on the size of your deployment, with one core supporting up to 100 users, though GitLab admits you'll experience slowness, which I can confirm. It's better to commit the recommended minimum two cores for starters. That will support up to 500 users and adds snappiness to the GUI and the GitLab services.

GitLab recommends 4GB of RAM for installations handling up to 100 users. I tested 2GB and 3GB—options that are possible—but performance suffered. Will it work with less memory? Yes, and it might be just fine if you rarely use the browser interface and rely instead on doing most of your work remotely from the command line. If your VM host is truly hurting for memory, I recommend starting with 2GB and going from there.

If you're starting your installation with two cores and 4GB of RAM, you can get away with committing at little as 10GB of storage for the GitLab installation and database. I set up my VM with 16GB, which worked fine.

By default, the GitLab installation will deploy PostgreSQL as the underlying database, which is highly recommended over MySQL and MariaDB, because those databases don't support all of GitLab's features. You can make it work if you must, but it's better to go with PostgreSQL.

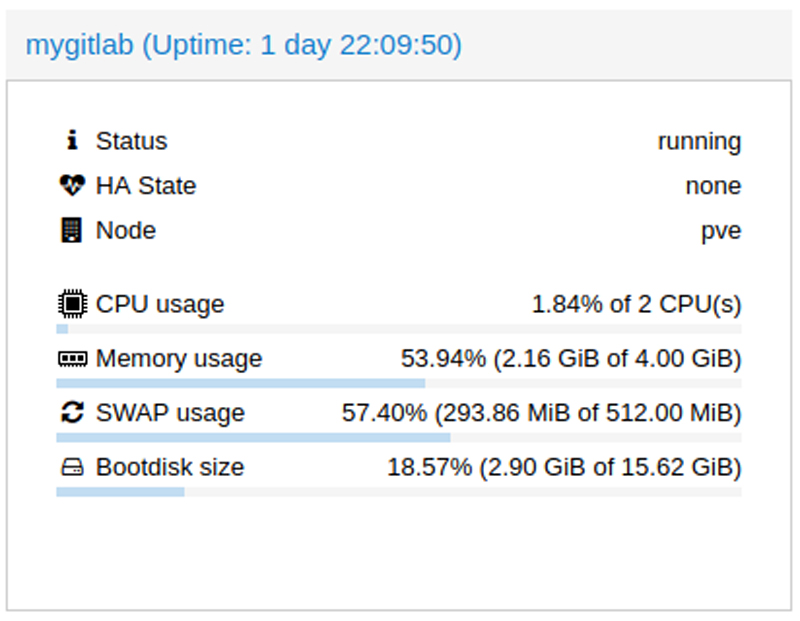

In the end, my GitLab deployment ended up sipping resources, and the VM resources looked like Figure 1 when it was running.

Figure 1. GitLab Running on an Ubuntu 16.04 VM with Minimal CPU, Memory and Storage

Note that when it's idle, GitLab is using hardly any CPU. When I ran a remote push, it barely moved CPU usage past 5%.

Finally, I finished my prep by adding an entry for my GitLab host on my DNS

servers so I could set the external_url config parameter during

installation and more easily access the host when cloning and pushing

projects. You probably can get away with editing the /etc/hosts file on

both your GitLab host and workstation instead of a full-fledged DNS setup

(and if you don't want to use the OAuth integration described later).

Installing GitLab CE took only three steps. The first was to ensure

curl,

openssh-server and ca-certificates were installed on the Ubuntu host:

$ sudo apt-get install -y curl openssh-server ca-certificates

Your GitLab server can send email if you install postfix, or you can skip

that step and configure an external SMTP server later.

The next step is adding the GitLab package repository to the Ubuntu

apt

sources, which is made easy with a bash script GitLab supplies:

$ curl -sS

https://packages.gitlab.com/install/repositories/gitlab/

↪gitlab-ce/script.deb.sh | sudo bash

For Ubuntu 16.04, it added the following sources if you feel like adding them manually:

deb https://packages.gitlab.com/gitlab/gitlab-ce/ubuntu/

↪xenial main

deb-src https://packages.gitlab.com/gitlab/gitlab-ce/ubuntu/

↪xenial main

With the package sources in place and updated, installation is done with a

routine apt command that includes the URL of your GitLab host added as a

parameter:

$ sudo EXTERNAL_URL="http://gitlab.example.com" apt-get

↪install gitlab-ce

Be sure to set this to the URL of your host. If you want to use HTTPS, you can do that, but you'll need to complete a couple more steps after the main installation. See the Resources section on how to do that with a self-signed certificate or with one supplied by a Certificate Authority. The total installation process takes just a few minutes and leaves you with a fully functioning GitLab server ready to go at the URL you specified.

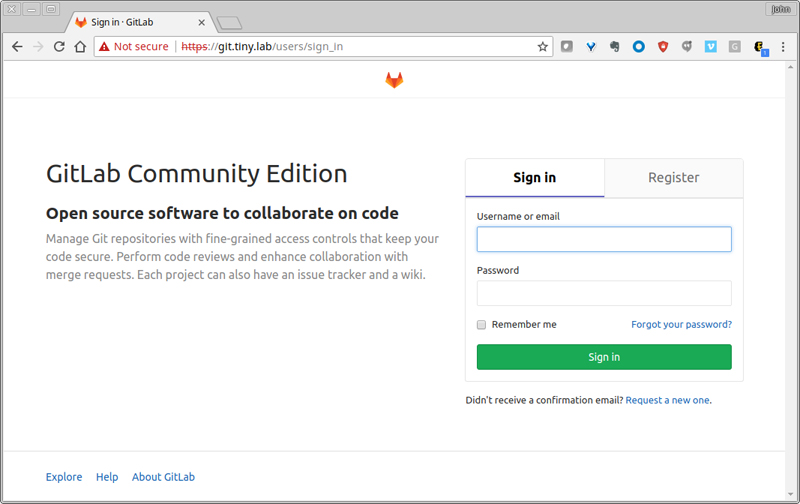

Figure 2. After installation, GitLab will be available at the URL you set. You'll see a password reset screen and then be taken to the main login page. Log in initially with the user name "root".

The first thing I did after logging in as "root" was to go into the admin settings (reachable from the little wrench icon in the main nav bar) and create a user account. I gave it the same name as my GitHub account for consistency and to make it easier to sync GitHub and GitLab repositories later. Once the new user was created, I logged out and logged back in with that account.

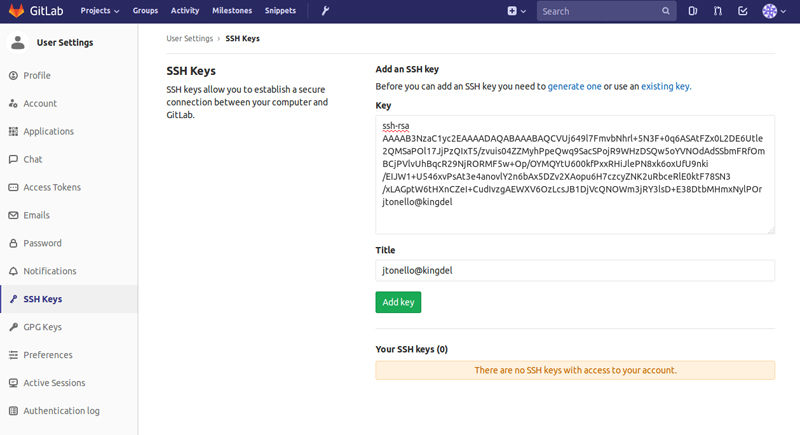

As with GitHub, you'll need to set up at least one SSH key to enable you to establish a secure connection between your workstation and your GitLab server. In the GitLab console, navigate to Settings and SSH Keys; the console shows you where to find your existing keys or how to create one, and warns you to paste in only the .pub part.

Figure 3. GitLab offers nice in-line hints on how to create your SSH keys.

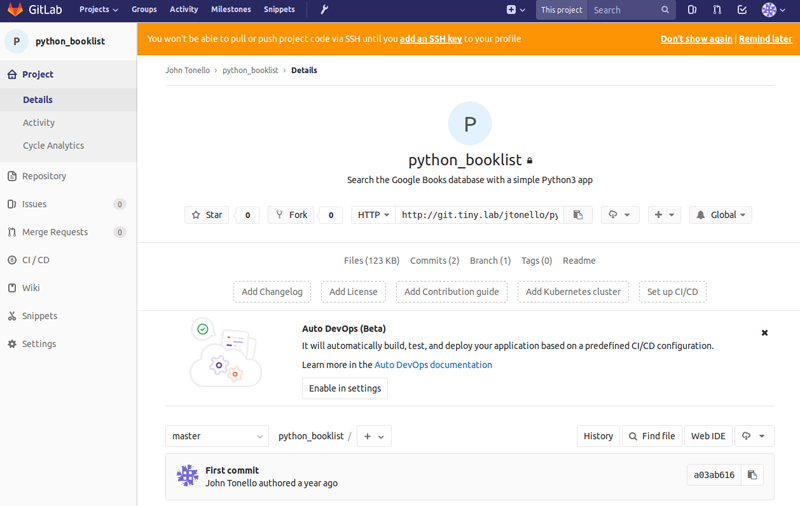

GitLab does a great job throughout of offering in-line instructions and tips, making it particularly easy to set up, even if you're brand new to Git and GitLab. For instance, if you start trying to create projects without first setting up at least one SSH key, GitLab warns you right in the console.

Figure 4. If you try to create a project without first setting up at least one SSH key, GitLab will warn you and link you to where you need to go.

If you're deploying GitLab with an intent to replace GitHub (or another public code repository), GitLab makes it straightforward by providing hooks right within the project-creation tooling.

GitLab offers two ways to set up integrations with GitHub: you can set up an OAuth application or use a Personal Access Token. GitLab recommends the OAuth method, because it associates all user activity on GitHub repositories with those on your self-hosted GitLab repositories. It's a nice integration that makes for a seamless transition. Using the Personal Access Token method is easier, but it doesn't give you all the bells and whistles.

GitLab also recommended using the same namespace (user name) in both services. So in my case, I created a GitLab account user name "jtonello" to match my GitHub one.

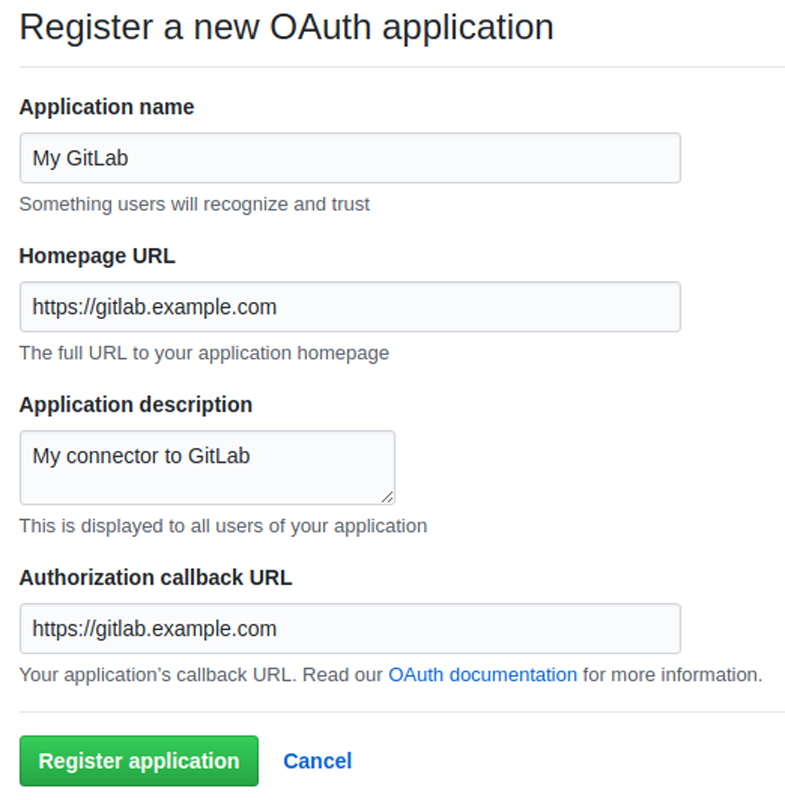

To start the integration, log in to your GitHub account, and navigate to Settings and Developer Settings. In the menu, choose OAuth Apps and click the "New OAuth App" button.

Here you'll provide some basic information, including an application name and the full URL to your GitLab application home page. Critical among these is the Authorization callback URL, which must be an address GitHub can reach. This is where setting up a fully qualified domain name on your GitLab server comes in handy. If you're working in a home lab on a NATed network, set up your router to forward port 80 or 443 to your GitLab server. In this way, you can use the WAN IP address of your router as your callback URL. I used my router's DDNS feature with No-IP to do this with a ddns.net domain name GitHub could see and communicate with.

Figure 5. When creating a new OAuth application in GitHub, make sure the Authorization callback URL matches that of your GitLab server and that it's accessible.

When you click the "Register application" button, you'll be taken to GitHub's OAuth application page, which shows a new Client ID and Client Secret for the application you just created. You'll use these to complete the setup back on your GitLab host. Don't share them. They're keys to your GitHub repository!

Back on your GitLab CE omnibus host, open /etc/gitlab/gitlab.rb, the main GitLab configuration file, and add the GitHub provider details you just created:

gitlab_rails['omniauth_providers'] = [

{

"name" => "github",

"app_id" => "YOUR_APP_ID",

"app_secret" => "YOUR_APP_SECRET",

"args" => { "scope" => "user:email" }

}

]

You'll also need to make a few changes in /etc/gitlab/gitlab.rb for the initial OmniAuth Configuration. In the omnibus version, uncomment and edit the following lines to look like this:

gitlab_rails['omniauth_enabled'] = true

gitlab_rails['omniauth_allow_single_sign_on'] = ['saml',

↪'twitter']

gitlab_rails['omniauth_auto_link_ldap_user'] = true

gitlab_rails['omniauth_block_auto_created_users'] = true

Once you save the file, you'll need to reconfigure your GitLab server, a step that automatically restarts the various GitLab services:

$ sudo gitlab-ctl reconfigure

Although the reconfigure command takes only a moment (you'll see activity

scrolling by on your terminal), be patient for the GitLab services to

restart. It may take a minute or two.

When the services are back up, go to the GitLab login page where you'll now see a GitHub login option. If all went well, you now can create a new project and import repositories directly from GitHub.

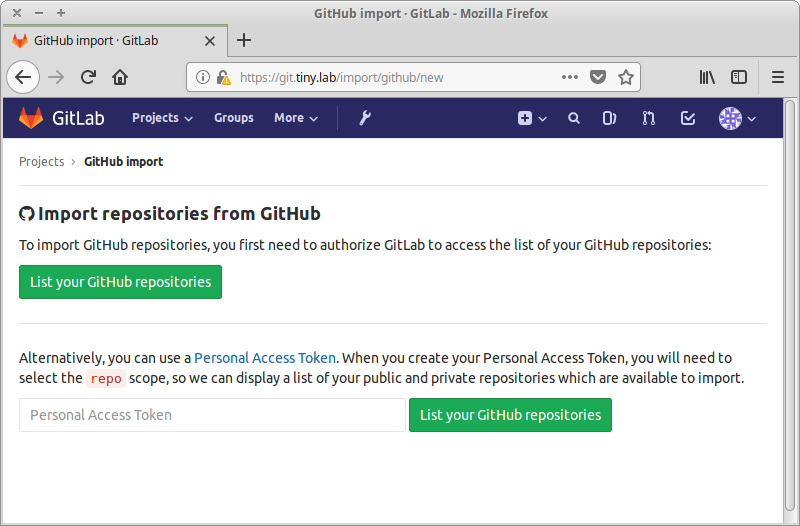

Do this by clicking the "New project" button on the GitLab Projects page and choosing "GitHub" from the list on the "Import project" tab. The first time you do this, you'll be prompted to authorize the OAuth connection with GitHub, and then you'll see a "List your GitHub repositories" button. If you've decided instead to use a Personal Access Token to create your link to GitHub, you'll see that here too.

Figure 6. Successful setup of the OAuth integration enables a direct view of GitHub repositories from within GitLab.

You'll know the authorization is successful if you see the import page, and you'll likely get an obligatory email from GitHub telling you that a third-party OAuth application has been added to you account.

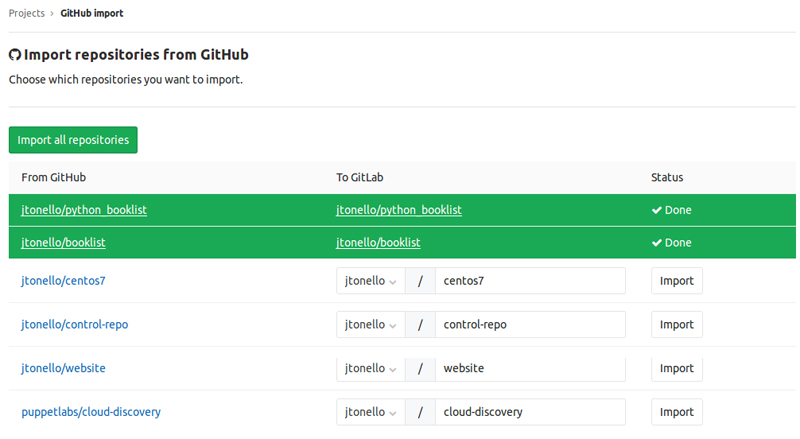

You now can choose to import some or all of your GitHub repositories. You can save them to your current user account or select another. Depending on the size of the repository and your network speed, this will take anywhere from a few seconds to a few minutes.

Figure 7. This view inside GitLab shows a complete list of your GitHub projects, which can be imported as is under the current user or a different GitLab user, or it can be renamed.

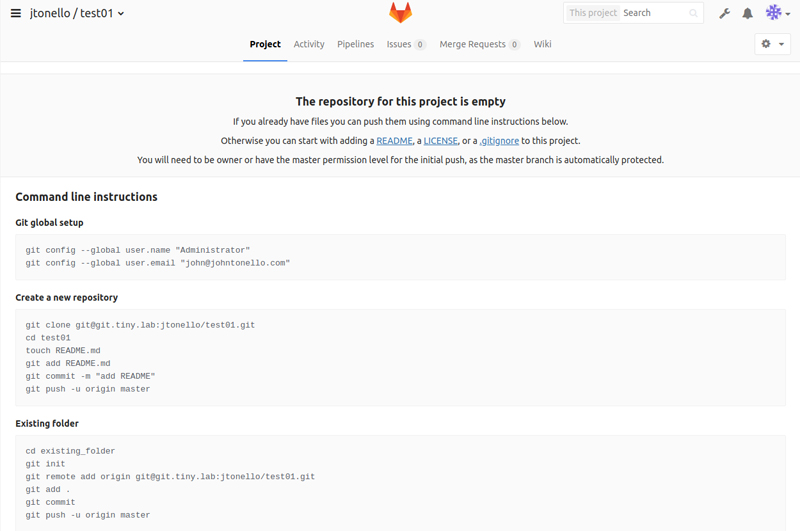

With GitLab up and running, go ahead and try to create some new projects or clone existing ones to your workstation. GitLab even shows you the commands to run (Figure 8).

Figure 8. When you create a new project in GitLab, it offers basic Git instructions on how to get started.

You're now ready to commit code and expand your Git skills.

John Tonello is Sr. Technical Marketing Manager for Puppet Inc. He's been a Linux user and enthusiast since building his first Slackware system from diskette 20 years ago.