The Bourne-Again SHell (Bash) was developed by the Free Software Foundation (FSF) under the GNU Project, which gives it a somewhat special reputation within the Open Source community. Today, Bash is the default user shell on most Linux installations. Although Bash is just one of several well known UNIX shells, its wide distribution with Linux makes it an important tool to know.

The main purpose of a UNIX shell is to allow users to interact effectively with the system through the command line. A common shell action is to invoke an executable, which in turn causes the kernel to create a new running process. Shells have mechanisms to send the output of one program as input into another and facilities to interact with the filesystem. For example, a user can traverse the filesystem or direct the output of a program to a file.

Although Bash is primarily a command interpreter, it's also a programming language. Bash supports variables, functions and has control flow constructs, such as conditional statements and loops. However, all of this comes with some unusual quirks. This is because Bash attempts to fulfill two roles at the same time: to be a command interpreter and a programming language—and there is tension between the two.

All UNIX shells, including Bash, are primarily command interpreters. This trait has a deep history, stretching all the way to the very first shell and the first UNIX system. Over time, UNIX shells acquired the programming capabilities by evolution, and this has led to some unusual solutions for the programming environment. As many people come to Bash already having some background in traditional programming languages, the unusual perspective that Bash takes with programming constructs is a source of much confusion, as evidenced by many questions posted on Bash forums.

In this article, I discuss how programming constructs in Bash differ from traditional programming languages. For a true understanding of Bash, it's useful to understand how UNIX shells evolved, so I first review the relevant history, and then introduce several Bash features. The majority of this article shows how the unusual aspects of Bash programming originate from the need to blend the command interpreter function seamlessly with the capabilities of a programming language.

The term "shell" originated from the MULTICS project, a collaboration between Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), General Electric and Bell Telephone Laboratories (henceforth Bell Labs) to develop a next-generation time-sharing operating system. Unhappy with the progress, Bell Labs withdrew from the project in 1969, and the Bell Labs team who worked on MULTICS went on to develop their own operating system: UNIX.

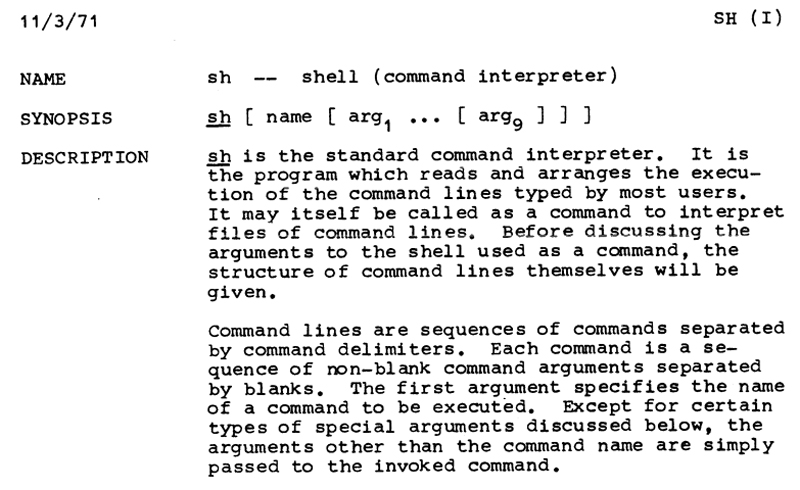

The ancestor of Bash is the Thompson shell, the first UNIX command interpreter, developed by Ken Thompson in 1971. Figure 1 shows an excerpt from the UNIX Programming Manual, 1st edition, that describes the Thompson shell.

Figure 1. An Excerpt from the UNIX Programming Manual, 1st Edition, Published in 1971, Describing the Original Thompson Shell

Between 1973–1975, John R. Mashey extended the original Thompson shell and added several programming capabilities, making it a high-level programming language. In Mashey's own words:

Modifications have been aimed at improving the use of the shell...and making it even more convenient to use as a high-level programming language. In line with the philosophy of much existing UNIX software, an attempt has been made to add new features only when they are shown necessary by actual user experience in order to avoid contaminating a compact, elegant system through "creeping featurism". (From J. Mashey, "Using a Command Language as a High-level Programming Language", CSE '76 Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Software engineering, 1976.)

Stephen Bourne started working on a new shell early in 1976. The Bourne shell benefited from the concepts introduced by the Mashey shell, and it brought some new ideas of its own. The Bourne shell officially was introduced in UNIX Version 7, released in 1979.

The original Thompson shell, the Mashey shell and the Bourne shell were all called sh, and they overlapped or replaced one another in the years 1970–1976 as they were refined and gained additional capabilities. Throughout 1970s, UNIX was mostly being developed at Bell Labs and, in parallel, at the University of California at Berkeley (the variant known as BSD). With the development of UNIX, shells were constantly developed and refined. At the time when the Bourne shell already was in use, Bill Joy at Berkeley developed the C shell (csh). The C shell was the first truly alternative UNIX shell, and it was incorporated in the 2BSD release of Berkeley UNIX. In the early 1980s, David Korn developed the Korn shell (ksh). Compared to the Bourne shell, the C shell emphasized the command interpreter mode, and the Korn shell came with more extensive programming capabilities.

UNIX development efforts at Bell Labs and Berkeley enriched each other, and the two versions were later merged. In the 1980s, AT&T licensed UNIX to a number of commercial vendors, and this resulted in the disruptive wars for the UNIX market domination. In 1985, Richard Stallman established the Free Software Foundation (FSF), whose main initiative was to build a free-to-use UNIX-like system, one that is not encumbered by the intellectual property issues surrounding UNIX. This is the famous GNU Project ("GNU's not UNIX"). In fact, the original letter from Stallman, sent on the net.unix-wizards mailing list in September 1983, started with the cry: "Free Unix!"

Since it's impossible to have free UNIX without a shell, that was a priority for the GNU Project. Brian Fox, the Free Software Foundation's first paid programmer, started working on a shell 1988. This became Bash, first released as beta in 1989. Bash is mostly a clone of the Bourne shell (hence "Bourne-Again"), but it also includes additional features inspired by the C shell and Korn shell. Brian Fox was the official maintainer of Bash until 1992. At the time, Chet Ramey already was involved with the work on Bash, and he became the official maintainer in 1993. Chet Ramey continued to maintain and develop Bash for the next 25 years, and he's still Bash's current maintainer.

The original Thompson shell was a simple command interpreter whose mode of operation was as follows:

$ command [ arg1 ... [ argN ]

where command is the name of the executable file (that is, a command to be executed), and the optional arguments arg1 ... argN are passed to the command. The Thompson shell had no programming capabilities. This changed with the development of the Mashey shell (and later the Bourne shell). In his seminal paper "The UNIX Shell", published in 1978, Stephen Bourne wrote:

The UNIX shell is both a programming language and a command language. As a programming language, it contains control-flow primitives and string-valued variables. As a command language, it provides a user interface to the process-related facilities of the UNIX operating system. (S.R Bourne, "The UNIX Shell", The Bell System Technical Journal, Vol 56, No 6, July–August 1978.)

Note the emphasis on the different functionality: a programming language and a command language. In fact, it was the Mashey and Bourne shells that extended the capabilities of the Thompson shell beyond the command interpreter. The shell's original role was a command interpreter, and the programming capabilities of shells were added later. UNIX shells evolved some ingenious ways of consolidating the programming capabilities with the original command interpreter role.

Today's Bash is more powerful compared to the original Mashey shell and the Bourne shell. However, the purpose of the shell remains exactly the same. Arguably, the most important function of the shell is running commands (that is, submitting an executable file to the kernel for execution). This has several profound ramifications. For a start, Bash treats (almost) anything that is given to it as a command. Consider the following Bash session:

$ VAR

bash: VAR: command not found

$ 9

bash: 9: command not found

$ 9 + 1

bash: 9: command not found

$

This shows that Bash splits the input into words, then attempts to execute the first word as a command (the "words" VAR and 9). Here, a "command" may be either a Bash built-in command (such as cd), a utility (such as /bin/ls) or some other executable file. When the string 9 + 1 was given on input, Bash split it into three "words": 9, + and 1. It's important to note that Bash keeps all words as strings and has no concept of numbers until forced to do an arithmetic evaluation. As a rather simplified summary, Bash operates as follows:

This view ignores several intermediate steps. For example, Bash scans the input line and performs all sorts of expansions and replacements. It also checks for a built-in command with the name given, and executes that, if it exists. Not to lose sight of the big picture, I often ignore these details.

So, Bash's most essential purpose is to execute commands, and this has some profound implications. Notably, the programming constructs in Bash, which at first sight may look like a programming language, are derived from this mode of operation. And, that is the central theme of this article.

The point that's often confusing to Bash newcomers is the difference between Bash built-in commands and external commands. On a typical Linux/UNIX system, a number of common commands are both built-in in Bash and also exist as independent executables with the same name. Examples of this include echo (built-in) and /bin/echo, kill (built-in) and /bin/kill, test (built-in) and /usr/bin/test (and there are more). Consider how the Bash built-in echo and /bin/echo behave very similarly:

$ echo 'Echoed with a built-in!'

Echoed with a built-in!

$ /bin/echo 'Echoed with external program!'

Echoed with external program!

$

However, there are also subtle differences (try echo --version). Why this duplication of commands? There are several reasons. The built-in version typically exists for performance reasons: Bash built-ins execute within the shell process that's already running. In contrast, executing an external utility involves loading and executing the external binary by the kernel, which is a much slower process.

At this point, it's useful to note that some shell commands, by their nature, cannot be external utilities (in other words, they must be shell built-ins). Consider the cd command that changes the current working directory. An external utility wouldn't be able to change the shell's current working directory, so cd must be a Bash built-in. Why? Because invoking a command as an external utility would make the shell its parent process, and a child process cannot change the current working directory of the parent process.

You could turn this question around and ask, "if echo is already built in to the shell, why does the external utility /bin/echo exist?" That's because one doesn't always work through the shell and may need to invoke echo without the mediating shell process. Second, in principle, there's nothing to enforce that a UNIX shell must have echo as a built-in, and therefore, it's important to have the external utility /bin/echo as a fallback.

A practical problem users often face is this: how do you know whether the command you just called is the shell built-in or an external utility with the same name? The Bash command type (which is itself a shell built-in) indicates what command would be used if executed. For example:

$ type echo

echo is a shell builtin

$ type ls

ls is hashed (/bin/ls)

$

The basic rule is as follows: if the built-in command with a given name exists, it will be executed. If the built-in command doesn't exist, Bash will search for an external program, and if found, will execute it. If you want to be sure to use the executable, which happens to have the same name as a shell built-in, calling the executable with the full path will do.

When a command is entered in Bash, Bash expects that the first word it encounters is a command. However, there's one exception: if the first word contains =, Bash will attempt to execute a variable assignment. For example:

$ VAR=7

$

This has assigned the value 7 to the variable named VAR. To retrieve the value of a variable, you need to prefix the variable name with the dollar sign. Thus, to view the value of a variable, you can combine the dollar-sign prefix with echo:

$ echo $VAR

7

$

For a variable assignment, a contiguous string that contains = is important. The following will fail:

$ VAR = 1

bash: VAR: command not found

$

In this case, Bash splits the input VAR = 1 into three "words" (VAR, = and 1) and then attempts to execute the first word as a command. This clearly isn't what was intended here.

Although Bash allows you to create arbitrary variables on the fly simply by assigning the values to them, it also has a number of built-in variables. An example of a built-in variable is BASHPID. This contains the process ID of the Bash shell itself:

$ echo $BASHPID

2141

$

Another built-in variable (and one that I cover extensively here) is ?. At any point in a Bash session, this variable contains the return value of the last executed command. The return value is always an integer. (And specifically, this is the return value of the C program function main(). Note: in any C program the function main() must return an integer.) By the UNIX convention, the return value of 0 denotes success, and any other value denotes failure. For example, consider the utility /bin/ls:

$ touch NEWFILE

$ /bin/ls NEWFILE

NEWFILE

$ echo $?

0

$

As per the convention, the utility /bin/ls returned 0 on success, which you can see by inspecting the value of ?. If ls is unable to execute (for example, unable to access the file), it returns the value >0:

$ /bin/ls DOESNOTEXIST

ls: cannot access 'DOESNOTEXIST': No such file or directory

$ echo $?

2

$ echo $?

0

$

In the last example, note that the first ? was set to 2, and the second ? was set to 0. Why? Because the second ? contains the exit status of the echo command (which executed successfully). Remember, the ? variable contains the exit status of the last executed command. You can use the commands true and false to set the value of ? to 0 or 1, respectively:

$ false

$ echo $?

1

$ false

$ true

$ echo $?

0

$

That might look rather silly at first, but keep reading.

Now let's consider how Bash provides an impression of a seamlessly integrated command environment, even when the tasks it executes are inherently quite different. First, note that running a Bash built-in command produces the same effect on the ? variable as running an external program:

$ false # set ? to 1

$ echo 'Calling a built-in command'

Calling a built-in command

$ echo $?

0

This example shows that calling the built-in command echo changed ? to 0 (to confirm this, first run the false command, which sets ? to 1). The point is that it behaves the same as calling the external program echo:

$ false # set ? to 1

$ /bin/echo 'Calling external program'

Calling external program

$ echo $?

0

Yet, these two scenarios are quite different. In the first scenario, Bash invoked an internal command echo; in the second example, Bash requested from the kernel to run an external executable (/bin/echo) and suspended itself waiting for the executable to complete. The effect on the ? variable is exactly the same.

Even for a variable assignment, Bash will set the ? variable accordingly:

$ false # set ? to 1

$ VAR=one

$ echo $?

0

$

From this, you can see that Bash treats a variable assignment as a command. If the variable assignment is not successful, ? is set to a value >0. For example, the built-in variable BASHPID is read-only, and you can't change it (that is, Bash can't change its own process ID). So this will fail:

$ true # set ? to 0

$ BASHPID=99

$ echo $?

1

$

Attempting to execute a non-existent command would also set ? to indicate a failure:

$ true # set ? to 0

$ DUMMY

bash: DUMMY: command not found

$ echo $?

127

$

In this case, Bash filled the special variable ? with the number 127. This number is hard-wired in Bash, and it specifically means "command not found".

To summarize, the above examples show three completely different scenarios: invoking an internal Bash command, running an external program and variable assignment. Yet, Bash views all three as command execution and provides a common behavior with respect to the ? special variable. Armed with these insights, now let's examine three basic programming constructs in Bash: the if statement, the while loop and the until loop.

if StatementThe fundamental element of almost every programming language is the conditional if statement. In the C language, it looks like this:

if (TRUTH_TEST) {

statements to execute

}

Here TRUTH_TEST is a test that evaluates true or false according to the rules of the C language. This is sometimes called "truth value testing". Here's an example of this in Python:

if True:

print('Yay true!')

In Bash, the same example looks like this:

if true

then

echo 'Yay true!'

fi

You can reformat this by using ; to provide a handy one-liner to type in:

$ if true; then echo 'Yay true!'; fi

Yay true!

$

This looks very much like the if conditional statement in any programming language. However, it's not. In the above example, true is a command. In fact, true is a shell built-in:

$ type true

true is a shell builtin

$ help true

true: true

Return a successful result.

Exit Status:

Always succeeds.

Let that sink in: true is a command. In fact, that's the same true command that was run above from the command line to set the value of the ? variable. What then is the if statement evaluating? It's evaluating the return value of the true command. If you're not convinced, consider that true can be replaced with the external utility /bin/true:

$ if /bin/true; then echo 'Yay true!'; fi

Yay true!

$

Where:

$ man true

TRUE(1) User Commands TRUE(1)

NAME

true - do nothing, successfully

SYNOPSIS

true [ignored command line arguments]

true OPTION

DESCRIPTION

Exit with a status code indicating success.

If true is a command, you can put any command there, right? Indeed:

$ if /bin/echo; then echo 'Yay true!'; fi

Yay true!

$

Notice how the blank line was printed before the string Yay true!. That's because the if statement actually executed the command /bin/echo, and without any arguments, this prints a newline character. You actually can give an argument to the echo command:

$ if /bin/echo 'Hi'; then echo 'Yay true!'; fi

Hi

Yay true!

$

The two echo commands executed here are different: the first is the external utility /bin/echo; the second, an echo that appears in the body of the if statement, is the shell built-in. Clearly, the second echo could be replaced with the external utility too.

Moving on, I mentioned previously that Bash will treat the variable assignment as a command. Thus, variable assignment can be used in the same place as the built-in command or external executable:

$ if VAR=99; then echo 'Assignment done!'; fi

Assignment done!

$ echo $VAR

99

$

To sum up, the general form of the if conditional statement is: if CMD1; then CMD2; fi where CDM1 and CMD2 are commands. The if statement controls flow by evaluating the exit code of the command CMD1: if CMD1 was successful (judging by the exit status of 0), then CMD2 is executed. This is rather different compared to truth value testing in most traditional programming languages, and it's the source of much confusion. I shall call this source of confusion number 1.

false CommandI just described how true is a command. So not surprisingly, there is a false, the exact opposite of true. For the Bash built-in:

$ type false

false is a shell builtin

$ help false

false: false

Return an unsuccessful result.

Exit Status:

Always fails.

$

And, there is an external utility with the same function:

$ man false

FALSE(1) User Commands FALSE(1)

NAME

false - do nothing, unsuccessfully

SYNOPSIS

false [ignored command line arguments]

false OPTION

DESCRIPTION

Exit with a status code indicating failure.

The commands true and false do nothing, but exit with the status 0 or 1, respectively. Since the if statement evaluates the exit code when deciding whether to execute the body, if true always succeeds, and if false always fails. Note that the exit value of true is 0, and the exit value of false is 1. This is somewhat counterintuitive, and it's the exact opposite of most programming languages. For example, in Python truth value testing, 0 is equated with False (boolean), and 1 is equated with True (boolean).

if Is Testing the Exit ValueLet's confirm that the if statement in Bash is merely testing the value of the program's exit value by writing a simple C program, true.c, that returns 1 (note, the real utility true returns 0, or success!):

int main() {

return 1;

}

This program doesn't do much; it merely returns 1 as the exit status. According to the UNIX convention, the exit status of 1 indicates a failure (no matter that the program may run just fine!). Let's compile and execute this program, and confirm that it returns an "unsuccessful" exit status to the shell:

$ gcc true.c -o true

$ ./true

$ echo $?

1

$

So, if you use this program in the if statement, the output won't be what you may expect:

$ if ./true; then echo 'Yay true!'; fi

$

In other words, the true command has "failed". This example confirms that all the if statement does is evaluate the exit status. It doesn't matter that the program runs just fine, exactly as intended; from the Bash perspective, a non-zero exit status indicates failure. This I shall call the source of confusion number 2.

Consider the following task: test if the file exists, and if it does, delete it. For this you can use the Bash built-in test command with the -e flag:

$ rm dum.txt # make sure file 'dum.txt' doesn't exist

$ test -e dum.txt # test if file 'dum.txt' exists

$ echo $? # confirm that the command test failed

1

$ touch dum.txt # now create file 'dum.txt'

$ test -e dum.txt # test if file 'dum.txt' exists

$ echo $? # confirm the command test was successful

0

$

Therefore, to test if the file exists, and if yes, delete it:

$ touch dum.txt # create file 'dum.txt'

$ if test -e dum.txt; then rm dum.txt; fi # file deleted

$

The key to note here is that if test -e dum.txt; then rm dum.txt; fi actually executes the command test -e dum.txt. In this case, test is a Bash built-in. As you might suspect, there is a /usr/bin/test utility that does the same thing and could be used to the same effect:

$ touch dum.txt # create file 'dum.txt'

$ if /usr/bin/test -e dum.txt; then rm dum.txt; fi

↪# file deleted

$

Now, Bash implements [ ] as a synonym for the built-in test command:

$ test -e dum.txt # command successful if file exists

$ [ -e dum.txt ] # exactly the same as previous example!

Note, [ -e dum.txt ] is a command. And this, of course, returns 0 on success and 1 on failure. Let's confirm:

$ rm dum.txt

$ [ -e dum.txt ]

$ echo $?

1

$ touch dum.txt

$ [ -e dum.txt ]

$ echo $?

0

$

With this understanding, you can repeat the above example with the [ -e ... ] construct:

$ touch dum.txt # create file 'dum.txt'

$ if [ -e dum.txt ]; then rm dum.txt; fi # file deleted

$

The last construct looks even more like the if control statement in most traditional programming languages. However, it's not. [ ] is a command—basically another way to call the built-in test command.

The surprises don't quite end there. In Bash, the if statement can take any number of commands separated by a semicolon, after the keyword if and before the body denoted with the keyword then. Something like this: if CMD1; CMD2; ... CMDN; then CMDN+1; CMDN+2; CMDN+M; fi. The if statement evaluates all commands sequentially and executes the body of the loop only if the exit status of the last command is 0 (a success by convention). Consider the following example:

$ if false; true; then echo 'Yay true!'; fi

↪# body will execute

Yay true!

$ if true; false; then echo 'Yay true!'; fi

↪# body will not execute

$

So in Bash, it's completely legal to write something like this:

$ if [ -e dum.txt ]; echo 'Hi'; false; then rm dum.txt; fi

Hi

$

This executes three commands given after if, and it never will execute the body (rm dum.txt) because the last command is false, which always fails (more precisely, returns a non-zero status). In summary, in place of a single command, you can use a list of commands. The overall exit status of such a command list is given by the exit status of the last command in the list. This I shall call the source of confusion number 3.

while and untilUnderstanding the behavior of the if statement is rather useful because the same behavior applies to while and until loops. Consider the following example:

$ while true; do echo 'Hi, while looping ...'; done

Hi, while looping ...

Hi, while looping ...

Hi, while looping ...

^C

$

Let's understand exactly what happened here. First, the while loop executed the true command and evaluated its exit status. Since the exit status of true is always 0, it executed the body of the loop (echo 'Hi, while looping ...'). Then it went back for another cycle of the same. Because the true command always runs with success, this created an infinite loop (which was broken with Ctrl-C). Since true is a command, you can replace it with any command. For example:

$ while /bin/echo 'ECHO'; do echo 'Hi, while looping ...'; done

ECHO

Hi, while looping ...

ECHO

Hi, while looping ...

ECHO

Hi, while looping ...

^C

$

Thus, this while loop merely alternates the execution of the two echo commands: /bin/echo, the external executable, and echo, the Bash built-in.

As you might suspect, the while construct can accept a command list, and in such a case, it would proceed to execute the body of the loop based on the exit status of the last command in the list. In other words, the general form of the while loop is as follows: while CMD1; CMD2; ... CMDN; do CMDN+1; CMDN+2; CMDN+M; done. For example:

$ while true; false; do echo 'Hi, looping ...'; done

$

In this example, the body of the loop is not executed because the last command is false (which always fails). The until loop works similarly:

$ until false; do echo 'Hi, until looping ...'; done

Hi, until looping ...

Hi, until looping ...

Hi, until looping ...

^C

$

In the case of the until loop, the body of the loop executes as long as the command listed after the keyword until is returning a non-zero exit status. Since the command false returns a non-zero exit status every time, the above example resulted in an infinite loop. And of course, in the general form, the until loop can accept command lists: until CMD1; CMD2; ... CMDN; do CMDN+1; CMDN+2; CMDN+M; done.

You may ask, if these loops merely execute two commands (or two command lists), how is it useful in practice at all? The commands that are tested in the loop may depend on some dynamic condition (for example, the number of bytes written to a file, or the type of network traffic and so on). The change in conditions may cause the command to fail or succeed. Also you can modify the Bash variable in the body of the loop, which leads to the use of loops similarly as shown here:

$ i=1

$ while [ $i -le 3 ]; do echo $i; i=$((i+1)); done

1

2

3

$

Here ((i + 1)) forces Bash arithmetic evaluation, and $((i + 1)) returns the resulting value; the construct [ $i -le 3 ] is a synonym for test $i -le 3 that performs arithmetic comparison. Note that from the perspective of Bash, this is a command that executes successfully or not:

$ i=1

$ [ $i -le 3 ]

$ echo $?

0

$ i=9

$ [ $i -le 3 ]

$ echo $?

1

$

This is why the [ $i -le 3 ] construct can be used after the while keyword, which expects a command (or a command list).

Bash is an independently implemented derivative of the Bourne shell produced by the GNU Project, with enhancements inspired by the C shell and the Korn shell. The original UNIX shell (the Thompson shell) was a simple command interpreter. Subsequently, the Mashey shell and the Bourne shell blended in programming capabilities. Since Bash is a direct descendant of the Bourne shell, it inherited all the key ideas of how a programming environment works. This includes how it blends the programming language with the command interpreter. And for that purpose, UNIX shells have evolved some ingenious solutions.

In Bash, the programming constructs look similar to those found in traditional programming languages. However, how those programming constructs inherently work is quite different. This can be rather confusing to people coming with some knowledge of the traditional programming languages (which is usually the case for Bash users). Here are the three main sources of confusion with Bash programming:

if, while and until evaluate the exit status of a command. Basically these constructs evaluate the following: "is the exit status zero?" By the UNIX convention, the exit status of 0 denotes success, and anything else denotes a failure.main(). Note that a program that runs just fine may return a non-zero exit status (I showed an example of this above). However, writing such programs is not recommended. It would break the convention, and it most likely will break other things since the entire environment relies heavily on this convention.My sincere thanks to Chet Ramey for his feedback on the draft of this article. I would also like to thank Isidora C. Likic for checking the text and examples.

Too many articles and books on this topic exist to list in this space, but if you're interested in learning more, we recommend these Linux Journal articles (and there are actually too many LJ articles to list here as well, but here are some to get you started):

Bash Videos:

Vladimir Likic holds a PhD in bioinformatics, and he has been using UNIX since 1991 and Linux since 1995. Originally from Europe, he lived in the US for a number of years and now calls Australia home. Follow Vladimir on Twitter: @unix_byte.