With significant performance gains and powerful extra features—like the ability to apply single firewall rules to entire groups of hosts and networks at once—ipset may be iptables' perfect match.

iptables is the user-space tool for configuring firewall rules in the Linux kernel. It is actually a part of the larger netfilter framework. Perhaps because iptables is the most visible part of the netfilter framework, the framework is commonly referred to collectively as iptables. iptables has been the Linux firewall solution since the 2.4 kernel.

ipset is an extension to iptables that allows you to create firewall rules that match entire “sets” of addresses at once. Unlike normal iptables chains, which are stored and traversed linearly, IP sets are stored in indexed data structures, making lookups very efficient, even when dealing with large sets.

Besides the obvious situations where you might imagine this would be useful, such as blocking long lists of “bad” hosts without worry of killing system resources or causing network congestion, IP sets also open up new ways of approaching certain aspects of firewall design and simplify many configuration scenarios.

In this article, after quickly discussing ipset's installation requirements, I spend a bit of time on iptables' core fundamentals and concepts. Then, I cover ipset usage and syntax and show how it integrates with iptables to accomplish various configurations. Finally, I provide some detailed and fairly advanced real-world examples of how ipsets can be used to solve all sorts of problems.

Because ipset is just an extension to iptables, this article is as much about iptables as it is about ipset, although the focus is those features relevant to understanding and using ipset.

ipset is a simple package option in many distributions, and since plenty of other installation resources are available, I don't spend a whole lot of time on that here.

The important thing to understand is that like iptables, ipset consists of both a user-space tool and a kernel module, so you need both for it to work properly. You also need an “ipset-aware” iptables binary to be able to add rules that match against sets.

Start by simply doing a search for “ipset” in your distribution's package management tool. There is a good chance you'll be able to find an easy procedure to install ipset in a turn-key way. In Ubuntu (and probably Debian), install the ipset and xtables-addons-source packages. Then, run module-assistant auto-install xtables-addons, and ipset is ready to go in less than 30 seconds.

If your distro doesn't have built-in support, follow the manual installation procedure listed on the ipset home page (see Resources) to build from source and patch your kernel and iptables.

The versions used in this article are ipset v4.3 and iptables v1.4.9.

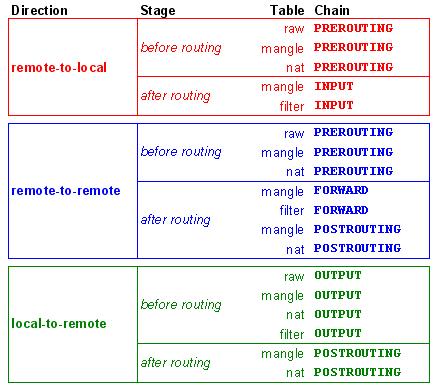

In a nutshell, an iptables firewall configuration consists of a set of built-in “chains” (grouped into four “tables”) that each comprise a list of “rules”. For every packet, and at each stage of processing, the kernel consults the appropriate chain to determine the fate of the packet.

Chains are consulted in order, based on the “direction” of the packet (remote-to-local, remote-to-remote or local-to-remote) and its current “stage” of processing (before or after “routing”). See Figure 1.

Figure 1. iptables Built-in Chains Traversal Order

When consulting a chain, the packet is compared to each and every one of the chain's rules, in order, until it matches a rule. Once the first match is found, the action specified in the rule's target is taken. If the end of the chain is reached without finding a match, the action of the chain's default target, or policy, is taken.

A chain is nothing more than an ordered list of rules, and a rule is nothing more than a match/target combination. A simple example of a match is “TCP destination port 80”. A simple example of a target is “accept the packet”. Targets also can redirect to other user-defined chains, which provide a mechanism for the grouping and subdividing of rules, and cascading through multiple matches and chains to arrive finally at an action to be taken on the packet.

Every iptables command for defining rules, from the very short to the very long, is composed of three basic parts that specify the table/chain (and order), the match and the target (Figure 2).

To configure all these options and create a complete firewall configuration, you run a series of iptables commands in a specific order.

iptables is incredibly powerful and extensible. Besides its many built-in features, iptables also provides an API for custom “match extensions” (modules for classifying packets) and “target extensions” (modules for what actions to take when packets match).

ipset is a “match extension” for iptables. To use it, you create and populate uniquely named “sets” using the ipset command-line tool, and then separately reference those sets in the match specification of one or more iptables rules.

A set is simply a list of addresses stored efficiently for fast lookup.

Take the following normal iptables commands that would block inbound traffic from 1.1.1.1 and 2.2.2.2:

iptables -A INPUT -s 1.1.1.1 -j DROP iptables -A INPUT -s 2.2.2.2 -j DROP

The match specification syntax -s 1.1.1.1 above means “match packets whose source address is 1.1.1.1”. To block both 1.1.1.1 and 2.2.2.2, two separate iptables rules with two separate match specifications (one for 1.1.1.1 and one for 2.2.2.2) are defined above.

Alternatively, the following ipset/iptables commands achieve the same result:

ipset -N myset iphash ipset -A myset 1.1.1.1 ipset -A myset 2.2.2.2 iptables -A INPUT -m set --set myset src -j DROP

The ipset commands above create a new set (myset of type iphash) with two addresses (1.1.1.1 and 2.2.2.2).

The iptables command then references the set with the match specification -m set --set myset src, which means “match packets whose source header matches (that is, is contained within) the set named myset”.

The flag src means match on “source”. The flag dst would match on “destination”, and the flag src,dst would match on both source and destination.

In the second version above, only one iptables command is required, regardless of how many additional IP addresses are contained within the set. Although this example uses only two addresses, you could just as easily define 1,000 addresses, and the ipset-based config still would require only a single iptables rule, while the previous approach, without the benefit of ipset, would require 1,000 iptables rules.

Each set is of a specific type, which defines what kind of values can be stored in it (IP addresses, networks, ports and so on) as well as how packets are matched (that is, what part of the packet should be checked and how it's compared to the set). Besides the most common set types, which check the IP address, additional set types are available that check the port, the IP address and port together, MAC address and IP address together and so on.

Each set type has its own rules for the type, range and distribution of values it can contain. Different set types also use different types of indexes and are optimized for different scenarios. The best/most efficient set type depends on the situation.

The most flexible set types are iphash, which stores lists of arbitrary IP addresses, and nethash, which stores lists of arbitrary networks (IP/mask) of varied sizes. Refer to the ipset man page for a listing and description of all the set types (there are 11 in total at the time of this writing).

The special set type setlist also is available, which allows grouping several sets together into one. This is required if you want to have a single set that contains both single IP addresses and networks, for example.

Besides the performance gains, ipset also allows for more straightforward configurations in many scenarios.

If you want to define a firewall condition that would match everything but packets from 1.1.1.1 or 2.2.2.2 and continue processing in mychain, notice that the following does not work:

iptables -A INPUT -s ! 1.1.1.1 -g mychain iptables -A INPUT -s ! 2.2.2.2 -g mychain

If a packet came in from 1.1.1.1, it would not match the first rule (because the source address is 1.1.1.1), but it would match the second rule (because the source address is not 2.2.2.2). If a packet came in from 2.2.2.2, it would match the first rule (because the source address is not 1.1.1.1). The rules cancel each other out—all packets will match, including 1.1.1.1 and 2.2.2.2.

Although there are other ways to construct the rules properly and achieve the desired result without ipset, none are as intuitive or straightforward:

ipset -N myset iphash ipset -A myset 1.1.1.1 ipset -A myset 2.2.2.2 iptables -A INPUT -m set ! --set myset src -g mychain

In the above, if a packet came in from 1.1.1.1, it would not match the rule (because the source address 1.1.1.1 does match the set myset). If a packet came in from 2.2.2.2, it would not match the rule (because the source address 2.2.2.2 does match the set myset).

Although this is a simplistic example, it illustrates the fundamental benefit associated with fitting a complete condition in a single rule. In many ways, separate iptables rules are autonomous from each other, and it's not always straightforward, intuitive or optimal to get separate rules to coalesce into a single logical condition, especially when it involves mixing normal and inverted tests. ipset just makes life easier in these situations.

Another benefit of ipset is that sets can be manipulated independently of active iptables rules. Adding/changing/removing entries is a trivial matter because the information is simple and order is irrelevant. Editing a flat list doesn't require a whole lot of thought. In iptables, on the other hand, besides the fact that each rule is a significantly more complex object, the order of rules is of fundamental importance, so in-place rule modifications are much heavier and potentially error-prone operations.

Outbound NAT (SNAT or IP masquerade) allows hosts within a private LAN to access the Internet. An appropriate iptables NAT rule matches Internet-bound packets originating from the private LAN and replaces the source address with the address of the gateway itself (making the gateway appear to be the source host and hiding the private “real” hosts behind it).

NAT automatically tracks the active connections so it can forward return packets back to the correct internal host (by changing the destination from the address of the gateway back to the address of the original internal host).

Here is an example of a simple outbound NAT rule that does this, where 10.0.0.0/24 is the internal LAN:

iptables -t nat -A POSTROUTING \

-s 10.0.0.0/24 -j MASQUERADE

This rule matches all packets coming from the internal LAN and masquerades them (that is, it applies “NAT” processing). This might be sufficient if the only route is to the Internet, where all through traffic is Internet traffic. If, however, there are routes to other private networks, such as with VPN or physical WAN links, you probably don't want that traffic masqueraded.

One simple way (partially) to overcome this limitation is to base the NAT rule on physical interfaces instead of network numbers (this is one of the most popular NAT rules given in on-line examples and tutorials):

iptables -t nat -A POSTROUTING \

-o eth0 -j MASQUERADE

This rule assumes that eth0 is the external interface and matches all packets that leave on it. Unlike the previous rule, packets bound for other networks that route out through different interfaces won't match this rule (like with OpenVPN links).

Although many network connections may route through separate interfaces, it is not safe to assume that all will. A good example is KAME-based IPsec VPN connections (such as Openswan) that don't use virtual interfaces like other user-space VPNs (such as OpenVPN).

Another situation where the above interface match technique wouldn't work is if the outward facing (“external”) interface is connected to an intermediate network with routes to other private networks in addition to a route to the Internet. It is entirely plausible for there to be routes to private networks that are several hops away and on the same path as the route to the Internet.

Designing firewall rules that rely on matching of physical interfaces can place artificial limits and dependencies on network topology, which makes a strong case for it to be avoided if it's not actually necessary.

As it turns out, this is another great application for ipset. Let's say that besides acting as the Internet gateway for the local private LAN (10.0.0.0/24), your box routes directly to four other private networks (10.30.30.0/24, 10.40.40.0/24, 192.168.4.0/23 and 172.22.0.0/22). Run the following commands:

ipset -N routed_nets nethash

ipset -A routed_nets 10.30.30.0/24

ipset -A routed_nets 10.40.40.0/24

ipset -A routed_nets 192.168.4.0/23

ipset -A routed_nets 172.22.0.0/22

iptables -t nat -A POSTROUTING \

-s 10.0.0.0/24 \

-m set ! --set routed_nets dst \

-j MASQUERADE

As you can see, ipset makes it easy to zero in on exactly what you want matched and what you don't. This rule would masquerade all traffic passing through the box from your internal LAN (10.0.0.0/24) except those packets bound for any of the networks in your routed_nets set, preserving normal direct IP routing to those networks. Because this configuration is based purely on network addresses, you don't have to worry about the types of connections in place (type of VPNs, number of hops and so on), nor do you have to worry about physical interfaces and topologies.

This is how it should be. Because this is a pure layer-3 (network layer) implementation, the underlying classifications required to achieve it should be pure layer-3 as well.

Let's say the boss is concerned about certain employees playing on the Internet instead of working and asks you to limit their PCs' access to a specific set of sites they need to be able to get to for their work, but he doesn't want this to affect all PCs (such as his).

To limit three PCs (10.0.0.5, 10.0.0.6 and 10.0.0.7) to have outside access only to worksite1.com, worksite2.com and worksite3.com, run the following commands:

ipset -N limited_hosts iphash

ipset -A limited_hosts 10.0.0.5

ipset -A limited_hosts 10.0.0.6

ipset -A limited_hosts 10.0.0.7

ipset -N allowed_sites iphash

ipset -A allowed_sites worksite1.com

ipset -A allowed_sites worksite2.com

ipset -A allowed_sites worksite3.com

iptables -I FORWARD \

-m set --set limited_hosts src \

-m set ! --set allowed_sites dst \

-j DROP

This example matches against two sets in a single rule. If the source matches limited_hosts and the destination does not match allowed_sites, the packet is dropped (because limited_hosts are allowed to communicate only with allowed_sites).

Note that because this rule is in the FORWARD chain, it won't affect communication to and from the firewall itself, nor will it affect internal traffic (because that traffic wouldn't even involve the firewall).

Let's say the boss wants to block access to a set of sites across all hosts on the LAN except his PC and his assistant's PC. For variety, in this example, let's match the boss and assistant PCs by MAC address instead of IP. Let's say the MACs are 11:11:11:11:11:11 and 22:22:22:22:22:22, and the sites to be blocked for everyone else are badsite1.com, badsite2.com and badsite3.com.

In lieu of using a second ipset to match the MACs, let's utilize multiple iptables commands with the MARK target to mark packets for processing in subsequent rules in the same chain:

ipset -N blocked_sites iphash

ipset -A blocked_sites badsite1.com

ipset -A blocked_sites badsite2.com

ipset -A blocked_sites badsite3.com

iptables -I FORWARD -m mark --mark 0x187 -j DROP

iptables -I FORWARD \

-m mark --mark 0x187 \

-m mac --mac-source 11:11:11:11:11:11 \

-j MARK --set-mark 0x0

iptables -I FORWARD \

-m mark --mark 0x187 \

-m mac --mac-source 22:22:22:22:22:22 \

-j MARK --set-mark 0x0

iptables -I FORWARD \

-m set --set blocked_sites dst \

-j MARK --set-mark 0x187

As you can see, because you're not using ipset to do all the matching work as in the previous example, the commands are quite a bit more involved and complex. Because there are multiple iptables commands, it's necessary to recognize that their order is vitally important.

Notice that these rules are being added with the -I option (insert) instead of -A (append). When a rule is inserted, it is added to the top of the chain, pushing all the existing rules down. Because each of these rules is being inserted, the effective order is reversed, because as each rule is added, it is inserted above the previous one.

The last iptables command above actually becomes the first rule in the FORWARD chain. This rule matches all packets with a destination matching the blocked_sites ipset, and then marks those packets with 0x187 (an arbitrarily chosen hex number). The next two rules match only packets from the hosts to be excluded and that are already marked with 0x187. These two rules then set the marks on those packets to 0x0, which “clears” the 0x187 mark.

Finally, the last iptables rule (which is represented by the first iptables command above) drops all packets with the 0x187 mark. This should match all packets with destinations in the blocked_sites set except those packets coming from either of the excluded MACs, because the mark on those packets is cleared before the DROP rule is reached.

This is just one way to approach the problem. Other than using a second ipset, another way would be to utilize user-defined chains.

If you wanted to use a second ipset instead of the mark technique, you wouldn't be able to achieve the exact outcome as above, because ipset does not have a machash set type. There is a macipmap set type, however, but this requires matching on IP and MACs together, not on MAC alone as above.

Cautionary note: in most practical cases, this solution would not actually work for Web sites, because many of the hosts that might be candidates for the blocked_sites set (like Facebook, MySpace and so on) may have multiple IP addresses, and those IPs may change frequently. A general limitation of iptables/ipset is that hostnames should be specified only if they resolve to a single IP.

Also, hostname lookups happen only at the time the command is run, so if the IP address changes, the firewall rule will not be aware of the change and still will reference the old IP. For this reason, a better way to accomplish these types of Web access policies is with an HTTP proxy solution, such as Squid. That topic is obviously beyond the scope of this article.

ipset also provides a “target extension” to iptables that provides a mechanism for dynamically adding and removing set entries based on any iptables rule. Instead of having to add entries manually with the ipset command, you can have iptables add them for you on the fly.

For example, if a remote host tries to connect to port 25, but you aren't running an SMTP server, it probably is up to no good. To deny that host the opportunity to try anything else proactively, use the following rules:

ipset -N banned_hosts iphash

iptables -A INPUT \

-p tcp --dport 25 \

-j SET --add-set banned_hosts src

iptables -A INPUT \

-m set --set banned_hosts src \

-j DROP

If a packet arrives on port 25, say with source address 1.1.1.1, it instantly is added to banned_hosts, just as if this command were run:

ipset -A banned_hosts 1.1.1.1

All traffic from 1.1.1.1 is blocked from that moment forward because of the DROP rule.

Note that this also will ban hosts that try to run a port scan unless they somehow know to avoid port 25.

If you want to clear the ipset and iptables config (sets, rules, entries) and reset to a fresh open firewall state (useful at the top of a firewall script), run the following commands:

iptables -P INPUT ACCEPT iptables -P OUTPUT ACCEPT iptables -P FORWARD ACCEPT iptables -t filter -F iptables -t raw -F iptables -t nat -F iptables -t mangle -F ipset -F ipset -X

Sets that are “in use”, which means referenced by one or more iptables rules, cannot be destroyed (with ipset -X). So, in order to ensure a complete “reset” from any state, the iptables chains have to be flushed first (as illustrated above).

ipset adds many useful features and capabilities to the already very powerful netfilter/iptables suite. As described in this article, ipset not only provides new firewall configuration possibilities, but it also simplifies many setups that are difficult, awkward or less efficient to construct with iptables alone.

Any time you want to apply firewall rules to groups of hosts or addresses at once, you should be using ipset. As I showed in a few examples, you also can combine ipset with some of the more exotic iptables features, such as packet marking, to accomplish all sorts of designs and network policies.

The next time you're working on your firewall setup, consider adding ipset to the mix. I think you will be surprised at just how useful and flexible it can be.